Churchill, Palestine and Israel, Part 1: 1917-1945

Remarks to Churchillians by the Bay, Richmond California, 10 February 2024. This text is without endnotes, though they can be found in my two Timelines on Palestine and Israel for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project: Part 1 (1945-46) and Part 2 (1947-49). Another version was published in The Amercan Spectator.

Palestine: “You deal with it.”

The best I can offer about Churchill and Palestine is what I learned from three great historians: David Fromkin, Martin Gilbert and Andrew Roberts. I also learned from King Ibn Saud of Arabia (not personally). I propose to quote all of them. And, of course, Winston Churchill. His knowledge and experience continue to instruct us across the decades.

David Fromkin was a leading authority on Churchill and the Middle East through his book, A Peace to End All Peace. You should read it. Twenty years ago during a Washington hurricane, he lectured on Churchill and the making of the modern Middle East. Only fourteen turned up, and his talk was never published. I corrected that recently on the Hillsdale Churchill website. As Casey Stengel said, you can look it up.

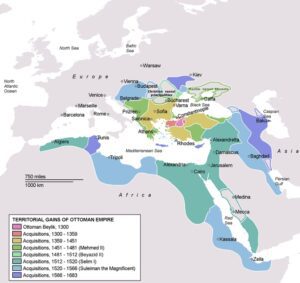

*Churchill and Palestine had a long association, spanning two world wars and thirty years. It began in 1917, when British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour promised a “Jewish National Home” in Palestine. Almost simultaneously, Lawrence of Arabia was offering the Arabs sovereignty over a Middle East ruled for nearly half a millennium by the Turks. In return, Jews and Arabs fought alongside the Allies in the Great War.

Churchill and Palestine came together because Turkey ended up on the losing side. By war’s end, its Ottoman Empire was a shambles. Revolutions and conspiracies were suspected among Arabs, Jews, Bolsheviks and recidivist Turks. The only significant military presence was a British army of about one million.

“At this truly horrendous moment,” Professor Fromkin told us, “Prime Minister David Lloyd George turned to his Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill and said in effect, ‘You deal with it.’”

Decision at Cairo

Churchill energetically expanded his Middle East Department, including T.E. Lawrence and Gertrude Bell. They met in Cairo with Arab and Jewish delegates to redraw the borders of the former Turkish empire.

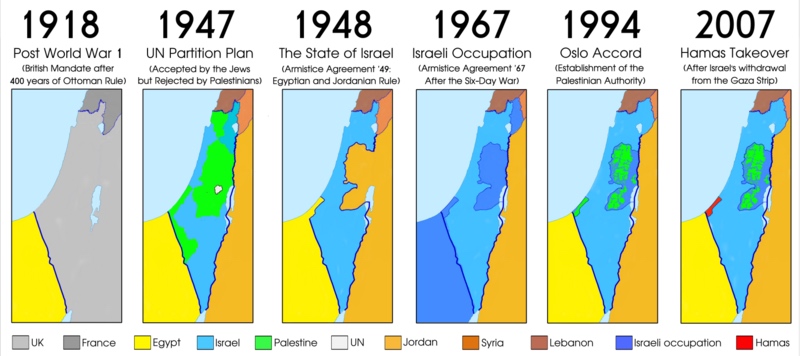

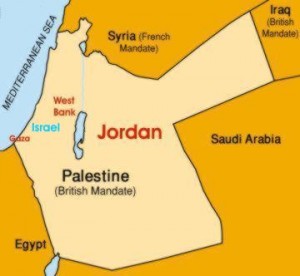

The 1921 Cairo Conference created the same Iraq, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon that are there today. The French received League of Nations mandates over the last two. An unenthusiastic Britain accepted mandates for Iraq and Palestine. East Palestine, 6/7ths of Palestine, became the Arab state of Trans-Jordan, meaning “across the Jordan River.” West Palestine, “from the river to the sea” (and the Negev Desert)—slightly larger than Massachusetts—became a source of strife that has lasted a century.

Now for Britain at least, despite what you may have heard, oil was not the objective. Before the war, Churchill had secured the Royal Navy’s supply by founding Anglo-Persian Oil Company (now BP). They thought Iraq had oil, but Britain had no need for it, and France did not begin thinking seriously about oil until later.

To run East Palestine (Trans-Jordan) and Iraq, the conference sent a Arab Hashemites, who were not indigenous. Dr. Fromkin explained: “The feeling at that time was that when you brought in a king for a new country, it ought to be somebody who is not from that country—not involved its internal feuds. You look for an outsider and a unifier.” His brother was sent to rule Iraq.

“Twice-promised land”

A mandate is sometimes said to be a polite word for a colony. That may have been how the French saw it, but for Britain, Iraq and Palestine were burdens. This is incidentally the origin of the myth that Churchill wanted to use poison gas on Iraqi rebels, which was cheaper than using troops. Actually he made a poor choice of words. He wanted tear gas, but his careless description of it as “poison” has left him no end of grief.

Churchill would happily have washed his hands of “Messpot,” as he called Mesopotamia, or Iraq. In 1922 he wrote, but didn’t send, a note to Lloyd George: “We are paying eight millions a year for the privilege of living on an ungrateful volcano, out of which we are in no circumstances to get anything worth having.” (£8 million then equals $725 million today.)*

King Faisal’s Iraq achieved nominal independence in 1932. Emir Abdullah’s Jordan took charge of East Palestine. Britain was left with troublesome little West Palestine—today’s Israel, Gaza, Judea and Samaria (the last two known collectively as the West Bank). For most of two decades Britain kept the peace. Superpowers have a way of doing that.

West Palestine experienced relative prosperity between the World Wars. But Jews and Arabs, who had lived between the River Jordan and the Mediterranean for thousands of years, had fought with the British and expected payback. Britain had promised them both homelands. West Palestine, wrote the historian Isaiah Friedman, was the “Twice-Promised Land.”

Two-State Solutions

Worse, no one at Cairo in 1921 anticipated the massive Jewish influx to West Palestine over the next 20 years. The causes were fivefold: drastic reduction of American immigration quotas; pogroms or expulsions of Jews in Poland, Russia and Arab countries; the great depression of 1929, Jewish persecutions in Nazi Germany, and powerful Zionist recruiting of Jews to the Holy Land.

Until 1937 Britain had promised only a Jewish homeland, not a state. London’s idea was an Arab-run West Palestine with freedom of religion and Jewish autonomous districts. But the sides could never reach agreement, and the Jewish population soared. In 1936 the Arabs began what they called “the Great Revolt,” three years of uprisings against British authority.

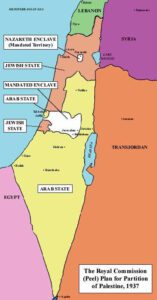

In 1937 William Peel (grandson of Sir Robert, founder of the Metropolitan Police) chaired a Palestine Royal Commission. It abandoned the former one-state solution. “There can be no question of fusion or assimilation between Jewish and Arab cultures,” Lord Peel declared. So the Peel Commission proposed the first of at least eight two-state solutions. (The eighth by my count was at Camp David in 2000.)

Peel proposed a Jewish state in the west and north, comprising 20% of West Palestine. The Arab state, linked to Jordan in the east and south, included the West Bank and the Negev Desert. Jerusalem, with a corridor to the sea, would be a British-administered international city.

The Jewish leaders Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion convinced the Zionist Congress to accept this. Both believed the area offered was too small, and hoped it could be expanded by negotiations. The Arabs, for whom any idea of a separate Jewish state was anathema, rejected the Peel proposal unanimously.

Economics trumps religion

Three more two-state solutions were advanced in 1938 by another commission under Sir John Woodhead, a civil servant. Weizmann offered a fifth solution, leaving the Negev in the Mandate, which Churchill approved. The Jews, said, had “a way of making the desert bloom.”

No one was satisfied. Woodhead had divided areas by majority population, but the average Jew was three times as productive and paid three times the taxes of the average Arab. The Jewish areas were the backbone of the economy. Most of the Arab wealth lay in largely Jewish areas. This is important for us to understand. The quarrel then was at least as much economic as it was religious. Another conference in 1939 made no further progress.

In May 1939, four months before war, the Chamberlain government issued a Palestine White Paper. It restricted Jewish immigration to West Palestine to 75,000 for the next five years, after which the Arabs were to decide on future numbers. This of course inflamed the Zionists, including Churchill. Two years earlier, Churchill had made one of his most criticized statements:

I do not admit that the dog in the manger has the final right to the manger, even though he may have lain there for a very long time… I do not admit, for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America, or the black people of Australia…that a wrong has been done to those people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher grade race, or, at any rate, a more worldly-wise race, to put it that way, has come in and taken their place.

King Saud: follow the money

Churchill has been excoriated for those words, and again his vocabulary didn’t help. For Churchill, “race” meant a nation or group of people. Indeed some African Jews were darker than Arabs. Churchill was saying the skills of what he called the “Jewish race” were superior to those of the Arabs. For example, the irrigation schemes of Jewish engineers brought productive agriculture to a long-barren land. Again, the argument was economic: follow the money.

One major Arab leader agreed with him. King Ibn Saud of Arabia said the Arab-Jewish conflict was not religious. What changed everything, he told President Roosevelt in 1945, was “the immigration of people who were technically and culturally on a higher level than the Arabs, [who] had greater difficulty in surviving economically. [That these] energetic Europeans are Jewish is not the cause of the trouble. It is their superior skills and culture.”

Azzam Pasha, Secretary General of the Arab League, later echoed the King: In Arab Palestine, he said, the Jews may be “as Jewish as they like. In areas where they predominate, they will have complete autonomy.” Whether he meant that you must judge for yourself.

“All legitimate interests are in harmony”

“Churchill,” he wrote, “continued to seek a Zionist solution whereby the 517,000 Jews, just under a third of the Arab population, would have their own State in which they would not be at the mercy of a hostile Arab majority, but able to govern themselves, albeit in only about a third of the area they had hoped for.”

Sir Martin quoted King Saud’s words to Churchill: “I have continually advised moderation to the Arabs with regard to Palestine, but fear that a clash might come.” When the war ended, Churchill replied, good arrangements can be made so that “all legitimate interests are in harmony.”

King Saud remained pessimistic. West Palestine Jews, he told Churchill, “intend to create a form of Nazi-Fascism within sight of the democracies and in the midst of the Arab countries…. Joshua captured the land of the Canaanites—an Arab tribe—with great cruelty and barbarity…. [They were] aliens who had come to Palestine at intervals and had then been turned out over two thousand years ago.”

A better scholar than I is needed to judge who was there first, or who turned out whom, but if Jews were expelled, then they too were refugees.

Further reading

“‘Jarring Gong’: Benjamin Netanyahu on Winston Churchill,” 2023.

“When Did Churchill Become a Zionist?,” 2022.

“Churchill at the Stroke of the Pen: Jordan and the Indian Army,” 2021.

“Churchill and Lawrence: Conjunction of Two Bright Stars,” 2020.

“Avaricious Imperialists or Nation Builders? The Middle East 100 Years On,” 2020.

One thought on “Churchill, Palestine and Israel, Part 1: 1917-1945”

Excellent work! I am grateful to have the necessary historical perspective and will share it widely.

Comments are closed.