“In Search of Churchill,” by Martin Gilbert: An Appreciation

Excerpted from “Pure Gold: Martin Gilbert’s In Search of Churchill,” written for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original article with more images, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, and fill in your email in the box entitled “Stay in touch with us.” Your email address is not given out and remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

A Churchillian Classic

Martin Gilbert, In Search of Churchill: A Historian’s Journey. London: HarperCollins; New York: Wiley, 1994), new paperback edition, $19.95, Kindle $11.39.

In Search of Churchill is one of Sir Martin Gilbert’s most captivating single volumes—as generous and humorous as its subject. For the dedicated student of Churchill, it is a panorama of rare experience. It is now available as a paperback and e-book. No dedicated Churchillian will put it down.

Sir Martin began his journey in 1962 at Stour, East Bergholt, the home of then-official biographer Randolph Churchill. Lady Diana Cooper had written a letter of introduction: “’Darling Randy, here is Martin Gilbert, an interesting researching historian young man who loves Duff and hates the Coroner. He is full of zeal to set history right. Do see him.” (“The Coroner” was Brendan Bracken‘s nickname for Neville Chamberlain. Lady Diana was referring to Randolph’s pet villain, but neither Martin nor Churchill hated political opponents.)

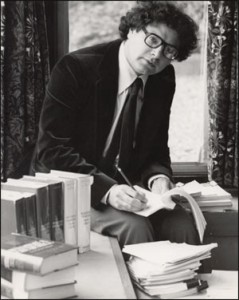

Gilbert became one of Randolph’s “Young Gentlemen,” helping to research and draft the “great work.” When Randolph died in 1968, Martin succeeded him. Today, Hillsdale College proudly houses the Gilbert Papers: 40 tons of material on Churchill, 20th Century and Jewish history. We lost Martin in 2015, but his work never dies. In 2019 Hillsdale completed The Churchill Documents from material he had compiled.

Personal testament

More than any of his nearly ninety works, In Search of Churchill is deeply personal. It is Martin’s answer to all those critics over the years (they are, in his polite way, never mentioned by name) who accused him of being uncritical. It is a self-defense manual for friends of Churchill: a smorgasbord of historical karate-chops.

Why was Gilbert so positive? Because time and again, In Search explains, he was prepared to find Churchill’s tragic flaw. And then he would come away more impressed with his wisdom, generosity and humanity. “I might find him adopting views with which I disagreed. But there would be nothing to cause me to think: ‘How shocking, how appalling.’”

“Beast of Bergholt”

Gilbert’s friends warned him he probably wouldn’t last long at East Bergholt. But Sir William Deakin, who had worked for Sir Winston, urged him to take the job anyway: “Working with Randolph, for however short a period, will provide a lifetime of anecdotes.”

Martin did survive, and Randolph anecdotes are served up wholesale. One glittering example involves the night a London newspaper editor was entertained at Stour. Randolph served him a fine repast, hoping to get the biography serialized in his newspaper.

The conversation turned to the truncated 1930s news reports from Berlin on the Nazi military buildup. The poor editor made the mistake of saying he had been responsible for cutting them. Randolph turned from the carving table, knife in hand, declaring: “You should have been shot by my father in 1940!” The editor, Martin recalls, left the next morning. (He felt able to spend the night!?)

Yet there are many vignettes attesting to Randolph’s kindliness toward his aides, his fascination with the fruit of their research, which he always referred to as “lovely grub.”

In search personally

Martin Gilbert found himself the official biographer, starting with the third volume. In Search devotes a chapter to the Dardanelles, the first great controversy he faced. Here we see his method of study: photocopy every relevant document, explore every source. If necessary, ring everyone named “X” in the London telephone book. Thus, he learned that initially it was Churchill who was wary about the Dardanelles campaign. Admiral Fisher, who later rebelled, was its backer. Churchill overextended himself defending an action he could not control. Then Fisher resigned, and Prime Minister Asquith formed a coalition with the Tories, whose price was Churchill’s departure.

Why did Asquith give in? Martin Gilbert could not comprehend it—until he found Judy Montagu, with whose mother, Venetia Stanley, Asquith was besotted at the time. Montagu brought him the priceless letters in which Asquith poured out his despondency after Venetia became engaged. Here was the “lovely grub” which structured Volume III’s account of Churchill’s worst political defeat.

In Search describes Churchill’s fearlessness in battle, combined with his detestation of war. Biographers who claim the opposite should read this: “Ah, horrible war,” says Churchill the warmonger: “If modern men of light and leading saw your face closer, simple folk would see it hardly ever.” He called the Second World War unnecessary and avoidable. He was rarely vindictive, but he never forgave the Prime Minister he held responsible: “I wish Stanley Baldwin no ill, but it would have been much better if he had never lived.” Sir Martin writes: “In my long search for Churchill, few letters have struck a clearer note than this one.”

“The factory”

“The factory”

In Search introduces us to the vast writing factory of Chartwell, with glimpses of it in action. Three chapters are devoted to literary assistants and secretaries. Some critics dwell on how much of their work Churchill passed off as his own. In fact, he signed off on every word, and his assistants loved him for the respect and appreciation he paid them.

Winston’s “secretaries” began with a Harrow school chum, John Milbanke, who took dictation while Churchill bathed. Milbanke later won the Victoria Cross, and was killed in action at Gallipoli. A succession of young people followed, and many told Sir Martin their experiences.

“One lady who worked with Churchill for just under three months in 1931, while he was in the United States, did not like him,” notes Martin. “She made her objections plain when, nearly 60 years later, she was interviewed at length by the BBC. It was curious, and for me distressing, that the other secretaries, who were with him for so much longer, and saw him at his daily work, were given far less time to say their piece.”

“Sagacious Cat”

A subject of much modern hindsight is Churchill’s marriage—which one well-publicized biography called a “loveless farce.” Sir Martin explored every paper, diary and memory touching on Churchill’s marriage and family: “I became aware of how close he had been to his wife and children—a closeness shown both by the time spent together, and intimate correspondence; an uninhibited and open relationship.”

In Search offers scores of examples of the love Clementine and Winston bore each other. One illustrates what Sir Martin calls “the unending fascination of the search.” He had written that Clementine, Winston’s “Sagacious Cat,” prevailed upon him to wear civilian dress in Paris to receive the Médaille Militaire in 1947. Later he learned, through a mutual friend of this writer’s, that WSC had for once rejected her advice, choosing the uniform of the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars. My friend Bill Beatty’s photo of the occasion appears in the book.

Even as he profited from these personal recollections, Gilbert admits that he is probably dealing with just a fraction of the record: “How often must Churchill have spoken on similar occasions, with no mechanical or human Boswell present, only a small group of listeners caught up in the force of his convictions, and realizing that they had listened to something rare, profound and extraordinary.”

“Golden inkwells”

In “Diaries and Diarists,” In Search describes the “golden inkwells” that mean so much to a biographer. Here we chop away at the vines of apocryphal stories choking the true image of Churchill. Gilbert himself admits falling for some: “I felt ashamed to have been caught telling them, being always so scornful myself of unauthenticated stories.”

“Dear Mr. Gilbert” is a grand finale chapter of spiraling fireworks and shooting stars. Amidst queries of every kind, Gilbert explodes ridiculous myths with which the public, and certain writers, seem besotted.

How did Churchill get by on so little sleep? (Actually he averaged seven to eight hours a day.) Did actor Norman Shelley deliver a Churchill speech over the BBC? (Never, though a cigar sometimes cluttered WSC’s delivery.) Is this signature or that painting a fake? (A surprising number are.) Did Churchill have royal blood? (undetermined) or illegitimate offspring? (No.) Was he unfaithful? (Never.) Did he rant against Jews? (Only Jews working with Lenin.) Did he lose the 1945 election with his “Gestapo Speech?” (“The Gestapo speech is always quoted, the social reform pledge hardly ever.”)

Prime Minister Edward Heath asked: How did Churchill work with his speechwriters? (“He didn’t use them,” said Martin, incurring the wrath of Heath’s speechwriter, later Britain’s foreign secretary.) Why are the Churchill papers on Dieppe open only to Martin Gilbert? (“This caused me to blow my top in Canada during a speech…. I said they were at the Public Record Office at Kew…. [The speaker] went on at a bright puce, and I have felt sorry for him ever since.”)

Eternal Chartwell

In Search of Churchill winds up at Chartwell, “where every vista, every artifact and every room has a story behind it.” Martin Gilbert recalls his many visits there over the years. Old hands pointed him both to obscure details and explained the central role Chartwell played in the saga.

Here, in Gilbert’s discrete way, are polite but firm rebuttals of silly stories spun by less fastidious biographers. Churchill’s alleged ego, lack of friends, heavy drinking, or his cavalier treatment of guests, are methodically debunked. Again, one quote will suffice, by Patrick Buchan-Hepburn, later Lord Hailes:

Winston was a meticulous host. He’d watch everyone all the time to see whether they wanted anything [and] was a tremendous gent in his own house. He was very quick to see anything that might hurt someone. He got very upset if someone told a story that might be embarrassing to somebody else in the room. Winston had a delicacy about other people’s feelings. In his house and to his guests he was the perfection of thoughtfulness.

More broadly, Buchan-Hepburn dismissed the vision of Churchill as a man who didn’t relate to ordinary people: “He had no class consciousness at all. He was the furthest a person could be from a snob. He admired brains and character; most of his friends were people who had made their own way.”

The real Churchill, the real Gilbert

I am well over my allotted space I haven’t told you the half of it. In Search of Churchill is pure gold—a book you simply must have. You may find yourself dog-earing or sticky-noting it for reference in confrontations with scoffers. It might well form part of the Official Biography itself. It is that warm, personal side of Martin Gilbert which he set out not to show in his biographic volumes.

Honest critics may argue over the merits of Martin’s approach, and the conclusions he draws. Martin himself admitted that he had barely scratched the surface. But fair-minded readers will come away from In Search of Churchill realizing that Sir Winston was lucky to have had such a biographer. Sir Martin has left a monument as stable and lasting as Chartwell itself.

2 thoughts on ““In Search of Churchill,” by Martin Gilbert: An Appreciation”

This just confirms what I have gathered in my readings of Mr. Churchill. What a magnificent man to read about and learn from.

Richard, a fine article about a splendid book. Martin inscribed my copy, “To Doug—-his favorite-and mine too! with the author’s regards Martin Alaska 15th September 2000” Your article has moved the book from the shelves to my stack for rereading. Thank you again.

Comments are closed.