Churchill and Lawrence of Arabia: A Conjunction of Two Bright Stars

Excerpted from “Great Contemporaries: T.E. Lawrence,” written for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the complete text and more illustrations, please click here.

Churchill and Lawrence

If the Almighty dabbles in the creation of individuals, He must have chortled when He conjured up Lawrence of Arabia. For here was the ideal adviser, foil and friend of Winston Spencer Churchill. To paraphrase WSC’s apocryphal quip, Lawrence possessed none of the virtues Churchill despised, an all the vices he admired.

He was “untrammeled by convention,” Churchill wrote, “independent of the ordinary currents of human action.” Arabs loved this fair-haired Westerner who helped wrest their homeland from the Turks in World War I. Then Lawrence wrote a book about it, of the same grandiloquent style as Churchill himself. An admiring Churchill leaned heavily on him after the First World War, and mourned his loss as the Second World War approached.

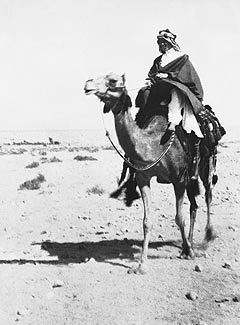

Lawrence claimed to care not a fig about his reputation, changed his name twice to stop it pursuing him. Yet Churchill thought that “he had the art of backing uneasily into the limelight. He was a very remarkable character, and very careful of that fact.” Lawrence for his part nursed that unqualified admiration for Churchill which was common among WSC’s friends. Churchill’s daughter Mary recalled his romantic image. “He would arrive at Chartwell of an afternoon, a short, nondescript, sandy-haired airman riding a motorcycle. Then he would dress for dinner, presenting himself in the flowing robes of a Prince of Arabia.” God simply couldn’t have invented a person Winston Churchill would have liked more.

Thomas Edward Lawrence…

…was born in North Wales in 1888 and began traveling in the Middle East while still an Oxford undergraduate. Obtaining a first class degree in history in 1910, he engaged in Middle East archeology, exploring the Negev Desert before joining the Geographical Section of the War Office in 1914. When the Arabs rebelled against the Turks, Britain saw an opportunity to secure a vital ally against the Central Powers. Lawrence was seconded to Ronald Storrs as a British representative to the Arabs. He became successively liaison officer, adviser, friend and promoter of the Emir Feisal, whom Churchill ultimately placed on the throne of Iraq. Feisal and his son ruled, unenlightened but in the main moderately, until the revolution of 1958, which ultimately produced Saddam Hussein.

The significance of Lawrence in the Arab revolt is a matter of discussion among historians. What is unarguable is that Lawrence wrote one of the best books to come out of World War I. A classic of English literature, his Seven Pillars of Wisdom was subtitled A Triumph. Among the triumphs were his surprise capture of Akaba in July 1917 and the conquest of Damascus in October 1918.

When he sat down to write the book, Lawrence worked largely from wartime notes. Then he lost the manuscript along with many notes, and began writing anew from memory. In 1926 he issued a private printing to a limited circle of subscribers including Churchill. A commercial edition called Revolt in the Desert followed, but it was an abridgement. Not until after his death did the full unabridged work appear, achieving posthumously his lasting fame.

Advocate for Arab justice

Lawrence accompanied Feisal to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919-20 with strong forebodings. He had for some time doubted Britain’s promises of independence if the Arabs helped win the war. Paris did not alter his doubts. Two years later, Churchill persuaded him to return from seclusion to join the Middle East Department of the Colonial Office. In 1921, Lawrence joined Churchill at the Cairo Conference, convened to fix the borders of the Middle East. For better or worse, those are the borders we still know today. At Cairo, Churchill argued vainly for a separate Kurdish homeland, “to protect the Kurds from some future bully in Iraq.” The Foreign Office thought his fears groundless.

The year before, France, feeling entitled to spoils of victory, had acquired League of Nations “mandates” in Syria and Lebanon. “Mandate” was polite shorthand for opportunistic colony grabbing, but Churchill sympathized. A nation “bled white by the war,” as Churchill put it, would tolerate nothing less. Britain received mandates in Palestine and Iraq. Though Iraq gained nominal independence in 1932, Britain continued to reap the benefit of the vast Iraqi oil fields. France, by contrast, ruled her mandates with her customary iron hand into World War II. Some analysts of French resistance to the 2003 Iraq War traced France’s attitude back to 1920, which left France with Syria, Lebanon, and no oil.

“The old men took our victory”

Lawrence never lost faith in Churchill, and thought he had addressed most Arab desiderata at Cairo. He was, however, profoundly disappointed by the Paris Peace Conference. A new world had beckoned, he wrote. Then “the old men came out again and took our victory to re-make in the likeness of the former world they knew.” Embittered, he rejected an honor by King George V at the moment of its presentation. Churchill rebuked him. It was “unfair to the King as a gentleman and grossly disrespectful to him as a sovereign.”

Lawrence renounced his past, enlisting in the Royal Air Force as “J.H. Ross” in 1922. A year later he joined the Royal Tank Corps as “T.E. Shaw.” In 1925, still as Shaw, he rejoined the RAF. He retired in 1935, shortly before his death on his Brough Superior motorcycle near his bungalow, Cloud’s Hill in Dorset. Visitors will find the cottage lovingly maintained by the National Trust, and a Lawrence Society exists to keep his memory.

Lawrence in retrospecct

Reflect on the time, now nearly a century ago, when he and Lawrence set out for Cairo. Their simple mission was to settle affairs in the Middle East. Today with clear hindsight we judge the mistakes and failures of that mission. It was not so clear at the time. Churchill wrote in Great Contemporaries:

…we had recently suppressed a most dangerous and bloody rebellion in Iraq, and upwards of forty thousand troops at a cost of thirty million pounds a year were required to preserve order. This could not go on. In Palestine the strife between the Arabs and the Jews threatened at any moment to take the form of actual violence. The Arab chieftains, driven out of Syria with many of their followers—all of them our late allies—lurked furious in the deserts beyond the Jordan. Egypt was in ferment. Thus the whole of the Middle East presented a most melancholy and alarming picture.

The modern equivalent of £40 million is $2 billion. The U.S. alone spent $750 billion in Iraq between 2003 and 2010. The UK spent £4.6 billion. Many more than 40,000 soldiers have been involved, and the picture is still melancholy and alarming. Arab chieftains, many our late allies, lurk furious in the deserts. President Harry Truman reflected: “the only thing that’s new is the history you don’t know.”

What may we learn…

…from Lawrence’s and Churchill’s ardent but ultimately failed efforts to promote Middle East peace? That those who ignore the lessons of the past are doomed to relive it? That Arabs are not the stereotyped gaggle of cutthroat fanatics some proclaim them to be? That some yearn for justice and a peaceful life? That the Twice-Promised Land—Lawrence to the Arabs, Balfour to the Jews—is a burden history has thrust upon us?

All of these, assuredly. But there is something more. And that is the innate decency and sense of fairness which animated Churchill and Lawrence. Some of that may glimmer in the recent Israel-UAE and Israel-Bahrain peace agreements. Those are qualities which will be needed in our statesmanship, if the lands Lawrence loved are ever to be placid and free.

“He was not in complete harmony with the normal”

The reader should turn now to Churchill’s Lawrence essay in Great Contemporaries. I will not quote it at length, because such beautiful writing deserves to be savored as a whole. But Churchill’s summary view is appropriate and true:

Those who knew him best miss him most; but our country misses him most of all, and misses him most of all now. For this is a time when the great problems upon which his thought and work had so long centred, problems of aerial defence, problems of our relations with the Arab peoples, fill an ever larger space in our affairs. For all his reiterated renunciations, I always felt that he was a man who held himself ready for a new call. While Lawrence lived one always felt—I certainly felt it strongly—that some overpowering need would draw him from the modest path he chose to tread and set him once again in full action at the centre of memorable events.

It was not to be. The summons which reached him, and for which he was equally prepared, was of a different order. It came as he would have wished it, swift and sudden on the wings of speed. He had reached the last leap in his gallant course through life.

“All is over! Fleet career,

Dash of greyhound slipping thongs,

Flight of falcon, bound of deer,

Mad hoof-thunder in our rear,

Cold air rushing up our lungs,

Din of many tongues.”*

* From “The Last Leap” by the Australian poet Adam Lindsay Gordon (1833-1870), who died by his own hand, nine years younger than Lawrence.

One thought on “Churchill and Lawrence of Arabia: A Conjunction of Two Bright Stars”

Two of my absolute heroes: and great writers, too. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom is as magnificent as Churchill’s Marlborough. Epic, eloquent works by brilliant, motivated men at the height of their creative genius, both of whom wielded the power of pen and sword, who could inspire armies and nations. Their mutual respect for each other, and particularly their writing, is abundantly and reassuringly clear in the correspondence they exchanged. ✌🏻🗡✒️📚

Comments are closed.