No, Churchill Didn’t Sink the Lusitania, Either

Excerpted from “Churchill Sank the Lusitania to Get America into the War,” written for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original article with footnotes and more images, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, enter your email in the box “Stay in touch with us.” Your email is never revealed and remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Churchill as sinker of ships? Sir Winston has been blamed for the loss of the Titanic, and for sinking the U.S. Pacific fleet (by not tipping off the Americans to his advance intelligence) at Pearl Harbor. Why not the Lusitania as well? No worries, the experts were on to that one years ago.

Lusitania redux

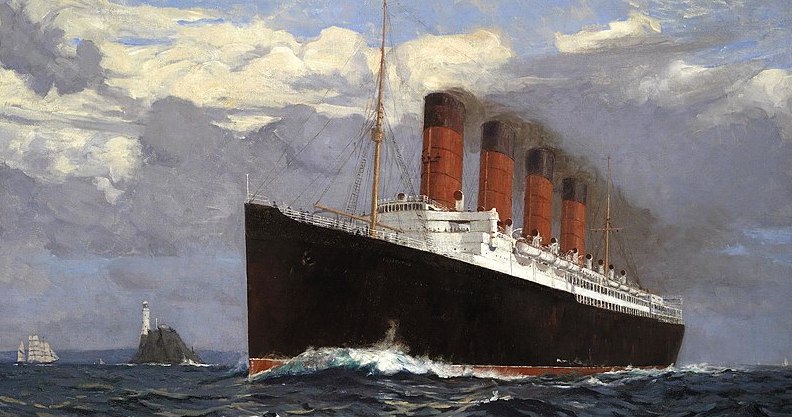

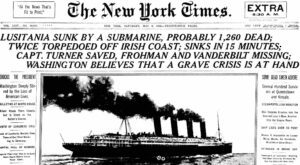

On 7 May 1915, Royal Mail Ship Lusitania was sunk within sight of land by a German submarine. Of her 1962 passengers and crew, 1199 (some estimates are higher) lost their lives. In the midst of the Dardanelles-Gallipoli crisis, the tragedy seemed incidental to some. Yet for a century, rumors swirled that Lusitania was deliberately sacrificed by the British, chiefly Churchill. His alleged aim was to infuriate the Americans, bringing them into the war against Germany. More recently, critics charged that Churchill’s Admiralty purposely contrived to steer the ship into harm’s way.

The complaint against Churchill reached critical mass in Colin Simpson’s The Lusitania (1972). This popular work was selected by four book clubs and excerpted in the Reader’s Digest and Life. Simpson’s charges have frequently been repeated, especially since the arrival of the Internet. As recently as 2014, a book on Franklin Roosevelt, The Mantle of Command, casually alleged that the Churchill had a role in the loss of the “ill-fated American liner.”

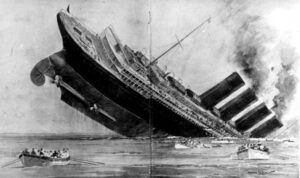

The Lusitania was British, not American, operated by Cunard, commanded by Captain William Turner RNR. Inbound from New York, she was torpedoed by the German submarine U-20 eleven miles off the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland. She experienced two explosions, the second catastrophic, and sank in only eighteen minutes. Among those lost were 128 Americans.

Scholarly testimony to the most logical events has been published, but lacking glitz and pathos, it tends to be ignored. Yet rebuttals to Simpson’s claims were in print long before his book, which mainly resurrected old canards.

“Armed cruiser containing troops and munitions”

After the sinking, the German government referred to its prior warnings to travelers to avoid the vessels of Germany’s enemies. Such ships were liable to be sunk, the Germans declared, particularly if they were armed. Simpson described the sighting of the liner, by Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger: “either the Lusitania or the Mauretania [her identical sister], both armed cruisers used for trooping.”

If that was how Schwieger saw her, it is inaccurate. RMS Lusitania (built in 1908 with possible wartime use in mind) did have twelve emplacements for small, six-inch guns. But she carried none. If she did, she certainly would have been an “armed cruiser.” Nor were any troops aboard.

Even if guns weren’t mounted, Simpson argued, they were there—not explaining what use they would be unmounted. Historian Thomas Bailey confounded even that argument, writing that a German reservist claiming to have seen mounted guns “confessed [to] perjury.” M.R. Dow, a reviewer with family connections to Cunard and the ship, wrote: “Simpson must have seen a German propaganda poster showing the Lusitania with guns popping out all over.”

“Explosives payload”

Another claim is that Lusitania carried a huge cargo of guncotton, whose detonation blew the bottom out. “This is also pure fantasy,” wrote Dow. Simpson’s explosives count nearly equalled “all the explosives delivered to the Western Front.”

Witnesses confirmed two explosions, the first caused by a German torpedo, the second of unknown but conspiratorial interest. The Lusitania was “loaded with munitions,” goes the story; these caused the second explosion, which did most of the damage. More recent scholarship suggests the second explosion occurred when incoming sea water hit the ship’s boilers.

The Germans’ best case for claiming that Lusitania was a ship of war was an order by the British Admiralty for merchant vessels to ram U-boats. But this was not their main line of defense. Speed, not ramming, was the ocean liner’s chief advantage. At her flank speed of 28 knots, Lusitania was three times as fast as a submerged U-boat, and nearly twice as fast as one on the surface.

Sailing into danger

The scholar Harry V. Jaffa placed most of the blame on human error: “Not only was her steam reduced; her crew was also…. Lifeboat davits were virtually unworkable from the moment the ship began to list. But the greatest of all the failures was the captain’s, since he navigated almost exactly as he would have done in peacetime.” Captain Turner had slowed down after striking the Irish coast in order to arrive with the tide at Merseyside.

In the 1930s, political opponents anxious to discredit Churchill’s warnings about Hitler claimed he had purposely endangered Lusitania. This view was widely held by the Germans, including the Kaiser, Bailey wrote: “No evidence has ever been presented to support the theory.”

In 1972, Simpson claimed that Lusitania had “sailing orders” instructing Turner to rendezvous with a naval escort, the cruiser HMS Juno, off southwest Ireland. This put her on a direct course for U-boat-infested areas. But Sir Courtenay Bennett, the British Consul-General in New York, was quoted by Simpson as saying no such orders were issued.

Captain Turner never referred to any orders, and Churchill said they would have made no sense. The navy did not have the resources to escort hundreds of merchant ships. Exceptions were sometimes made, but not for fast ships like Lusitania. “In a channel, where she could not maneuver, the Lusitania might well have needed an escort,” Jaffa wrote. “But why she should need one forty miles west of Fastnet is something it was incumbent upon Mr. Simpson to explain.”

Lusitania “was now alone”

The second allegation against Churchill is a meeting said to have occurred on 5 May 1915 in the Admiralty map room. Present were Churchill, First Sea Lord Fisher, Chief of Naval War Staff Admiral Oliver, Director of Naval Intelligence Captain Hall, and Commander Kenworthy of Naval Intelligence. On the map were markers denoting U-20 (apparently the British knew exactly where she was), Juno and Lusitania, “closing Fastnet at upwards of 20 knots.”

Simpson writes: “Admiral Oliver drew to Churchill’s attention the fact that the Juno was unsuitable for exposure to submarine attack without escort, and suggested that elements of the destroyer flotilla from Milford Haven should be sent forthwith to her assistance.” Here, Simpson wrote, “the Admiralty War Diary stops short…. Shortly after noon on May 5 the Admiralty signaled Juno to abandon her escort mission and return to Queenstown…. The Lusitania was not informed that she was now alone….

Churchill’s “conspiracy”

The “Admiralty War Diary” mentioned in this melodramatic paragraph appears nowhere else in Simpson’s book, not even the bibliography. No historian has found it. Professor Jaffa concluded that it was mix of accurate records and sheer supposition: “However much the ebullient Churchill interested himself in naval operations, it was not his primary task to make operational decisions”—particularly in the presence of Fisher, with whom Churchill was then “quarreling bitterly over the Dardanelles.” (Fisher resigned ten days later.)

The only eyewitness Simpson offered was Commander Joseph Kenworthy, later Baron Strabolgi, a Liberal turned Labourite and prominent pacifist. In his 1927 book, The Freedom of the Seas, he said Lusitania “was sent at considerably reduced speed into an area where a U-boat was known to be waiting and with her escorts withdrawn.” The only part of this that is credible is the last four words.

HMS Juno (laid down 1898) made no sense as an escort. Her top speed was 19.5 knots, well below Lusitania’s. It might be argued that Turner with his “sailing orders” slowed to rendezvous with Juno, having not been “informed” he was “now alone.” But Turner, who survived, never confirmed this.

Sailing orders that did exist

In recounting the tragedy in 1937, Churchill himself quoted four distinct Admiralty orders:

6 May, 0050: To all British ships: Avoid headlands. Pass harbours at full speed. Steer mid-Channel course. Submarines off Fastnet.

6 May, 0750: To Lusitania: Submarines active off south coast of Ireland.

7 May, 1125: To all British ships: Submarines active in southern part of Irish Channel. Last heard of south of Coningbeg Lighthouse. Make certain Lusitania gets this.”

7 May, 1240: To Lusitania: Submarines five miles south of Cape Clear proceeding west when sighted at 10 am.

The ship acknowledged all these messages.

Summary

Except for Kenworthy’s account, no other evidence, even circumstantial, exists of a conspiracy to sink the Lusitania. The chief cause of her loss was Captain Turner’s decision, after sighting the Irish coast, to proceed northward at reduced speed to “make the tide” at Merseyside, as he would have in peacetime. He did not avoid headlands. He did not zig-zag, a routine precaution in submarine-infested waters. Though he had the time, he did not head out to deeper waters, maintaining speed to minimize the danger. At his normal cruising speed, there was far less chance of a successful torpedo attack. There was no advantage and every danger in slowing down.

Should destroyers have accompanied her? Perhaps. But as Lusitania historian David Ramsay noted: “…the Dardanelles operation entailed the diversion from home waters of destroyers—the one class of ship in which the Royal Navy had a negligible superiority over the Germans. Commenting on the loss of the Lusitania…Admiral Duff wrote: ‘Indirectly the Dardanelles operation contributed; the [destroyers] that should be guarding merchant shipping are being used there.’”

Ramsay, writing in 2004, confirmed the findings of Bailey and Jaffa. He also quoted historians Stephen Roskill and David Stafford, “who are at one in rejecting any conspiracy, by Churchill or anyone else.”

Related articles

“Who Sank the Titanic? Hopefully Not Churchill Again,” 2019.

“Churchill Knew About Pearl Harbor,” 2015.

“Sinking the Lusitania”, by The Churchill Project, 2020. The first chapter of Nigel Hamilton’s book, The Mantle of Command, states that RMS Lusitania was an “ill-fated American liner.” He leaves the impression that Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, had played a role in the sinking in order to get the United States into the First World War. Any comment?

“Churchill Contentions: The Age of Fable and Myth,” by Richard M. Langworth, 2020. Churchill, who won a Nobel Prize, and did a few other things, cannot reply. He lies at Bladon in English earth, “which in his finest hour he held inviolate.” He’d love the controversy he stirs, on media he never dreamed of. He once said the vision “of middle-aged gentlemen who are my political opponents being in a state of uproar and fury is really quite exhilarating to me.”