Churchill and Lincoln: Scholars Consider the Cooper Union Speech

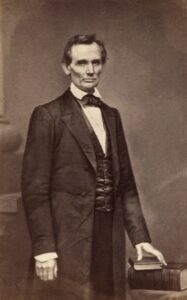

Cooper Union, 27 February 1860

Abraham Lincoln in 1860 confronted as existential a threat as Churchill as Prime Minister in 1940. A recent podcast of the Hillsdale Dialogues offers thoughtful comparisons.

Lincoln 1860, Churchill 1940

“Lincoln and Churchill found themselves challenged by wars of national survival,” writes the Lincoln scholar Lewis Lehrman. “Even though their early lives appear to be different, there are similar aspects in their educational preparation….

In June 1860, Lincoln wrote that “when I came of age I did not know much…. The little advance I now have upon this store of education, I have picked up from time to time under the pressure of necessity.”

Churchill in March 1949 would echo these remarks at Massachusetts Institute of Technology: “I frankly confess that I feel somewhat overawed in addressing this vast scientific and learned audience.… I have no technical and no university education, and have just had to pick up a few things as I went along.”

Their observations undervalued the immense effort both had put into self-improvement. At 23, Lincoln had stated in his first political campaign that education is “the most important subject which we as people can be engaged in.” At that age Lincoln was hard at work…at the study of grammar…. By age 45 he had mastered Euclid.

We are reminded again of these shared traits by Hillsdale College President Larry Arnn and author and broadcaster Hugh Hewitt. On October 27th, they discussed Lincoln’s 1860 Cooper Union speech on the weekly Hillsdale Dialogues.

What does “demonstrate” mean?

It is ironic that the greatest speech in American constitutional history was delivered at Cooper Union, where on October 26th Jewish students sheltered or hid from fanatical “demonstrators.” That is an interesting word, demonstrate. A digression is in order, because Lewis Lehrman’s reference to Lincoln and Euclid was repeated by Dr. Arnn, who offered something Lincoln said in 1859:

Reading law, I kept coming across the word “demonstrate.” I thought at first that I understood its meaning, but soon became satisfied that I did not. What do I mean when I “demonstrate”? More than when I reason or prove? How does “demonstrate” differ from any other proof? I consulted Webster. “Certain proof,” he says it means. I thought a great many things were proved beyond a possibility of doubt without recourse to any such extraordinary process of reasoning. So I said to myself, Lincoln, you will never make a lawyer if you do not understand what “demonstrate” means. I left my situation in Springfield, went home to my father’s house, and stayed there. until I could give any proposition in the six books of Euclid at sight. I then found out what “demonstrate” means, and went back to my law studies.

“Can you imagine any modern politician saying that?” Dr. Arnn asks. Evidently, we have somewhat obfuscated the meaning of the word “demonstrate.”

“Adamant in principle, moderate in practice”

Arnn and Hewitt deftly analyze Lincoln’s Cooper Union speech—as vital an oration as Churchill at M.I.T. in 1949 or Harvard Yard in 1943. In the beginning, Lincoln brilliantly demolishes the constitutional arguments for slavery. What catches the eye particularly today, however, are certain later paragraphs. They begin with his definition of conservatism:

What is conservatism? Is it not adherence to the old and tried, against the new and untried? We stick to, contend for, the identical old policy on the point in controversy which was adopted by “our fathers who framed the government under which we live”; while you with one accord reject, and scout, and spit upon that old policy, and insist upon substituting something new.

True, you disagree among yourselves as to what that substitute shall be. You are divided on new propositions and plans, but you are unanimous in rejecting and denouncing the old policy of the fathers.

What is the modern application of Lincoln’s precepts? It is, says Dr. Arnn, to proclaim when one does not agree with “something new,” but to do so prudently: “I counseled somebody in politics lately. I said you must couple two things together, because they are of a piece. You should be adamant in principle, and moderate in practice. And in tone.”

Lincoln to Republicans

Lincoln’s concluding words at Cooper Union are immortal. He spoke first to his party, then to his countrymen. He began with moderation:

A few words now to Republicans. It is exceedingly desirable that all parts of this great confederacy shall be at peace, and in harmony, one with another. Let us Republicans do our part to have it so. Even though much provoked, let us do nothing through passion and ill temper. Even though the southern people will not so much as listen to us, let us calmly consider their demands, and yield to them if, in our deliberate view of our duty, we possibly can. Judging by all they say and do, and by the subject and nature of their controversy with us, let us determine, if we can, what will satisfy them.

“Right makes might…”

Underneath that moderation lay the steel of principle:

Let us be diverted by none of those sophistical contrivances wherewith we are so industriously plied and belabored—contrivances such as groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong, vain as the search for a man who should be neither a living man nor a dead man—such as a policy of “don’t care” on a question about which all true men do care—such as Union appeals beseeching true Union men to yield to disunionists, reversing the divine rule, and calling not the sinners but the righteous to repentance—such as invocations to Washington, imploring men to unsay what Washington said, and undo what Washington did.

Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the government nor of dungeons to ourselves. Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.

Or as Churchill said, in a similar circumstance: “I refuse to be impartial as between the fire brigade and the fire.”

One yearns for a politician able to express their sentiments today.

Further reading

“Churchill’s Steady Adherence to His ‘Iron Curtain’ Speech, 2021.

“Churchill’s Ersatz Meeting with Lincoln’s Ghost,” 2018.