Churchill and Racism: Think a Little Deeper

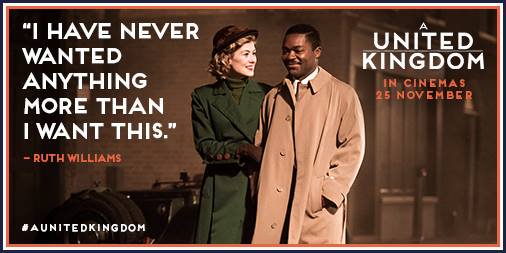

Q: Another new movie, A United Kingdom, saddles Churchill with racism. It’s the story of Seretse Khama of the Bechuanaland royal family and heir to the throne. After studying in England, he meets and marries a British woman, Ruth Williams. The South African government, which is adopting Apartheid, is troubled by the interracial marriage. It presses the Attlee government in Britain to exile Khama, which they do. Churchill is not a character in the film, but we are told that he supports Khama and will restore him if Churchill’s party wins the 1951 election. Churchill does win, but now we are told he has exiled Khama for life. The movie as usual compresses history and tells us at best a version of the truth. I am wondering if the Churchill part of the story is accurate. —P.L., Richmond, Va.

Q: Another new movie, A United Kingdom, saddles Churchill with racism. It’s the story of Seretse Khama of the Bechuanaland royal family and heir to the throne. After studying in England, he meets and marries a British woman, Ruth Williams. The South African government, which is adopting Apartheid, is troubled by the interracial marriage. It presses the Attlee government in Britain to exile Khama, which they do. Churchill is not a character in the film, but we are told that he supports Khama and will restore him if Churchill’s party wins the 1951 election. Churchill does win, but now we are told he has exiled Khama for life. The movie as usual compresses history and tells us at best a version of the truth. I am wondering if the Churchill part of the story is accurate. —P.L., Richmond, Va.

______

A: It is not. I heard about this and bounced it off others, because I am a bit busy fending off nonsense about Churchill in “Viceroy’s House,” “The Crown,” and other Drama that Goes Bump in the Night. A colleague replies:

The Labour government exiled Khama in 1951, when he returned to England where he had been a Law student. In 1956 he was allowed to return as a private citizen before entering politics in 1961. As for the charge of racism, you can’t compare today with the 1950s. It was a different world.

Contrary to the film, Churchill did not promise to end Khama’s exile if elected, then withdraw it and exile him for life. Commonwealth Relations Minister Lord Ismay warned the incoming Churchill cabinet that his return would provoke South Africa’s racist government. They would resort to economic sanctions and demand annexation of Bechuanaland, kept out of their hands since the Union of South Africa in 1910. (The Churchill Documents, Vol. 23, 34.) Khama and Ruth returned home in 1956. In 1966 he was elected first president of independent Botswana. Under Khama (1966-80), Botswana developed one of the world’s fastest growing economies. It boasts a record of uninterrupted democracy. Their son Ian was Botswana’s fourth president, serving 2008-18.

Racism?

Another Churchill scholar, author of a recent book on Churchill’s thought, challenges even the “different world” excuse. by responding as follows. This is certainly something to think about. Anyone reading this may do so. Note particularly the bold face:

Of course, and you can quote Abraham Lincoln in precisely the same sense, and also most of America’s founders (who abolished slavery in two-thirds of the Union during their lifetimes). The remarkable thing is not that any of them, or Churchill, had the standard view of questions like intermarriage. There was almost no experience with that and the prejudice against it was universal or nearly so.

The remarkable thing is that Lincoln, for the slaves, and Churchill, for the Empire, believed that people of all colors should enjoy the same rights, and that it was the mission of their country to protect those rights.

Therefore to say that Winston Churchill was “a man of his time,” or that “everyone back then was a racist,” is to miss the singular feature.

We spend a lot of time arguing that Churchill was remarkable. Then when something comes along that we do not like, we excuse it or explain it as typical of the age. I do not think Churchill was typical of the age on this question, if the age was racist.

Another thing to remember was that Lincoln and Churchill were political men. Also they were democratic men. They needed, and thought it was right that they needed, the votes of a majority. If they lived in an age of prejudice (and every age is that) then of course they would be careful how they offended those prejudices.

See also “Churchill as Racist: A Hard Sell”

4 thoughts on “Churchill and Racism: Think a Little Deeper”

It is true that the British government did not cave to Jan Smuts, either under Labour or the Tories. By the Fifties, the National Party was in power in South Africa. I think there is a case to be made that the British government did cave to the NP, which, of course, had no legal power to annex what was at that time British protectorates. The Afrikaners believed that South Africa was sovereign, and that the sovereignty of her neighbors was a fit topic for discussion. That’s why they considered the annexation of South West Africa, and sent troops into the Republic of Angola to fight for Jonas Savimbi. British policy on South Africa was to denounce Apartheid while cashing in on it.

=

I think those are valid points and thank you for making them, though Smuts was out of office after 1948. My point is that Churchill rebuffed Malan’s and the National Party’s efforts to annex Bechuanaland (and two other black protectorates) when he was in office (1951-55). South Africa never annexed South West Africa but illegally treated it as a province in the high-tide of Apartheid, and did send troops into Angola, but this was well after Churchill’s time. My focus is on Churchill’s actions while in power. These are discussed in more detail in “The Art of the Possible: Churchill, South Africa, Apartheid, Mandela.” RML

I was also curious about this point in the film, and an alternative source states:

Unmoved, the government announced its decision on 27 March I952. Ministers argued that their predecessors, having quite rightly concluded that Seretse was ‘not a fit and proper person’ to be chief, had then been guilty of ‘ a classic example of procrastination in public affairs’. Peace was hardly likely to be achieved by continuing uncertainty’; ‘temporary exclusion’ must therefore now be turned into permanent non-recognition. This was a line of argument the Labour opposition found hard to rebut.

(THE POLITICAL CONSEQUENCES OF SERETSE KHAMA: BRITAIN, THE BANGWATO AND SOUTH AFRICA, 1948-1952. Author: RONALD HYAM. The Historical Journal, 29, 4 (I986), pp. 92I-947)

=

Thanks, point taken. Hyam is a reliable historian. -RML

As my correspondent noted, it is broadly true. I have not read the book and would be interested in your take on it. We do know that Smuts, a segregationist when young, extended old age and disability payments to native blacks and Indians, and lost the 1948 election (in which only whites voted) after supporting the Fagan Commission, which recommended relaxing segregation. But Smuts died in 1950, so he could not have influenced the 1951 Churchill government. South African ruling circle opinion may however have been a factor. As another scholar writes (last paragraph above), Churchill, like Lincoln, was a politician, needing the votes of a majority in an age of prejudice, and that has to be borne in mind.

Is it accurate that when running for office, WSC said he’d lift the ban, then, once elected as PM, the ban was extended to life? I have bought the book specifically to read about it, instead of just viewing the movie.

A quick read of the pages with WSC’s name connected, appears as though he “caved” to Smuts of South Africa. Will read more thoroughly when I have time but that’s my quick read.

Thus, questions aren’t whether WSC was a man of his times and/or a racist, but, rather was he a person who took a very liberal position when running and then a horribly harsh one once elected?

Comments are closed.