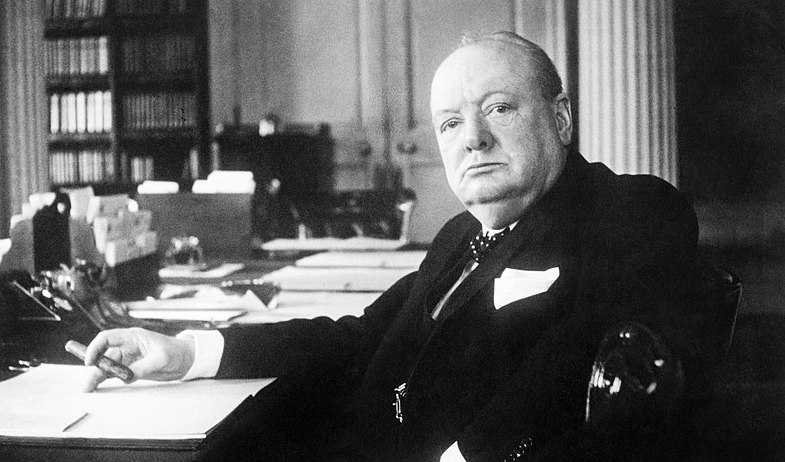

80 Years On: Winston Churchill Prime Minister, 10 May 1940

The 10th of May…

In the splintering crash of this vast battle the quiet conversations we had had in Downing Street faded or fell back in one’s mind. However, I remember being told that Mr. Chamberlain had gone, or was going, to see the King, and this was naturally to be expected. Presently a message arrived summoning me to the Palace at six o’clock. It only takes two minutes to drive there from the Admiralty along the Mall. Although I suppose the evening newspapers must have been full of the terrific news from the Continent, nothing had been mentioned about the Cabinet crisis. The public had not had time to take in what was happening either abroad or at home, and there was no crowd about the Palace gates.

I was taken immediately to the King. His Majesty received me most graciously and bade me sit down. He looked at me searchingly and quizzically for some moments, and then said, “I suppose you don’t know why I have sent for you?” Adopting his mood, I replied, “Sir, I simply couldn’t imagine why.” He laughed and said, “I want to ask you to form a Government.” I said I would certainly do so. —Winston S. Churchill, “The Gathering Storm,” 1948

Churchill explained that his commission did not extend to creating a national government. But in the crash of events, and Germany’s invasion in the West, he believed a coalition was essential. He had always favored coalitions in grave times. Now he would call upon members of all parties to “stand by the country in the hour of peril.”

The Grand Coalition

The Labour Party leader Clement Attlee shortly arrived, with Arthur Greenwood. Would they join a coalition under his leadership? They would. Both entered the Cabinet, Attlee as Lord Privy Seal. Churchill received a similar commitment from Sir Archibald Sinclair, leader of the Liberal Party, who became Air Minister. Magnanimity prevailed. Defying criticism from Chamberlain friends-turned-enemies—he made Chamberlain Lord President of the Council.

It was a remarkable collection of talent and former critics. Chamberlain’s stalwart ally Lord Halifax remained Foreign Secretary. Anthony Eden went to the War Office, A.V. Alexander to the Admiralty. It was probably the easiest task Churchill would have for many months. He reflected that in the recent past, he had come “far more often into collision with the Conservative and National Governments than with the Labour and Liberal Oppositions.” Churchill himself remembered his chief past failure, over the Dardanelles. Then he had attempted to direct “a cardinal operation of war” without plenary authority. Not this time: “I assumed the office of Minister of Defence, without however attempting to define its scope and powers.” Churchill continued:

Thus, then, on the night of the 10th of May, at the outset of this mighty battle, I acquired the chief power in the State, which henceforth I wielded in ever-growing measure for five years and three months of world war, at the end of which time, all our enemies having surrendered unconditionally or being about to do so, I was immediately dismissed by the British electorate from all further conduct of their affairs.

Honor to them all, heroic figures from “all parties and all points of view,” who came together and, eventually, prevailed. On this night of the 10th of May, raise a glass to Old Excellence.

Comments

Any thoughts from readers will be posted here. An old friend, escaped from the Nazis to Belgium, got out in time to America, had a distinguished academic career, and is still going strong…

I still vividly remember waking up on this day 80 years ago in Antwerp and hearing thunder but seeing no clouds. My mother told me that war had begun, and I felt joy about not having to go to school. Only later did I learn that this day was important for Mr. Churchill as well. A truly unforgettable day, almost a century ago. All through the years I always felt relief that things had gotten better than that day. For the first time now, I lack that confidence. -M.W.

My grandfather was a housemaster at Winchester College in 1940. Then as today, Winchester has no central dining. Boys eat in their boarding houses. One day in the summer term of 1940 Phil, a small boy in my grandfather’s house was walking back to his house, late for lunch. Phil loved my grandfather dearly, and told me this story at least twice. As he walked, he was behind two elderly housemasters. Both had fought in World War I and one had been a POW. Neither knew he was behind them. One said, “I really don’t see any choice. We are going to have to surrender. There’s no possibility of our surviving otherwise.” The second agreed. After lunch the worried Phil asked my grandfather: “Is it really true Sir? Are we going to have to surrender?” My grandfather didn’t pause: “Of course we are going to win!” Phil replied, “But Sir, how do you know?” My grandfather said: “Churchill says so, and that’s good enough for me!” From that moment Phil never doubted that we would win the war. -R.B.