The Greatness of Alex Tremulis: A Car Designer from Another Era (1)

My Tremulis piece was published in full in The Automobile, March 2020.

“That was a different time,” Alex Tremulis told me, recalling his heyday in car design. “The Forties through the Seventies. Back then a single person could often influence the shape of a car. Sometimes the whole car. Of course, lots of our ideas were sheer rubbish. But now and then, by luck or force of personality, we put something good into production.”

Many famous automotive designs did have whimsical beginnings. Bill Boyer put portholes on the rear roof quarters of the 1956 Ford Thunderbird to recall “the coachwork heritage.” They became so iconic that they reappeared on the retro-Bird in 2002. Dutch Darrin gave the seminal 1951 Kaiser its belt-line dip and vast glass area, which spread throughout the industry. Inspired by fighter aircraft, GM’s Ned Nickles created the postwar Buick’s “gunsight” mascot and fender portholes. Sarah Ragsdale, wife of a GM engineer, inspired the “hardtop convertible.” (She loved the sportiness of convertibles, but always drove with the top up to spare her coiffure.) “Nowadays, where design is largely spun by computers,” Alex Tremulis continued, “you can’t imagine the fairyland our business was back then.”

Starting at the Top

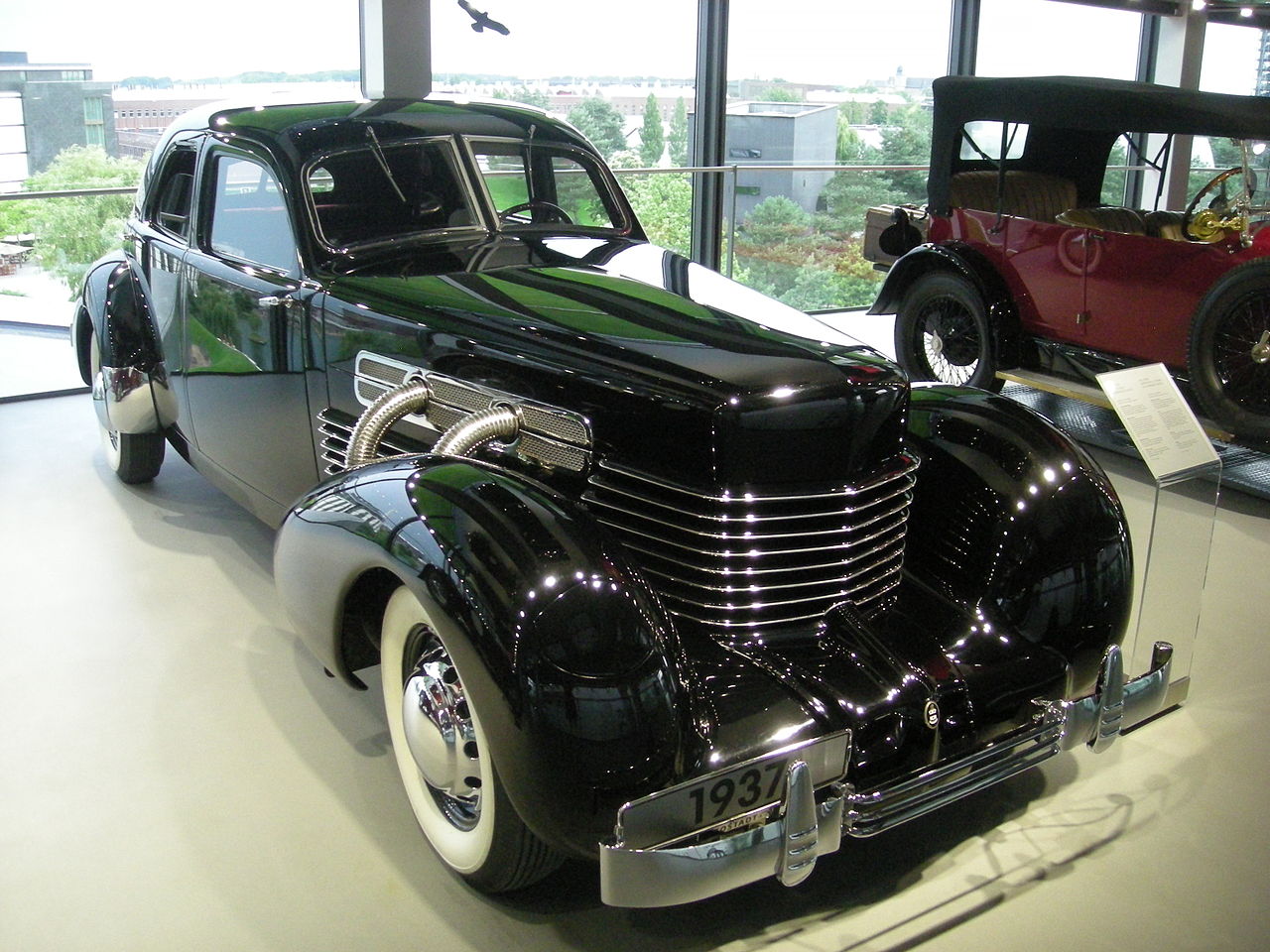

Unlike many of his styling colleagues, Tremulis was reticent to blow his own horn. He always credited the famous “coffin nose” 1936-37 Cord to Gordon Buehrig, whom he regarded as a genius. When pressed, however, he’d admit that it was he who gave the car its famous outside exhaust pipes. Buehrig, whom Alex replaced as chief designer for Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg, never really liked them. Later he acknowledged that they had become a hallowed trademark.

Alex once told me he was “proud to be a Spartan.” His Greek immigrant parents, Antonia and Sarantos, came from a village near that city. Alex was born in Chicago in 1914. His family was well off, so he grew up driving Stutzes, Templars and Mercedes. His education ended after high school, and he had no formal design or engineering training. Yet at the age of nineteen, he found himself at Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg, helping to create some of the fleetest and most beautiful cars on American roads.

* * *

In 1936, when Buehrig left, Alex became A-C-D’s chief stylist. “He had real inborn talent,” Gordon Buehrig told this writer. “He produced many exciting shapes, but unfortunately A-C-D was a goner. Between the Depression and E.L. Cord’s stock market machinations, they were out of business by 1938.”

Alex moved to California to build custom bodies for Hollywood society. While there he designed a convertible for American Bantam, formerly the American Austin. Bantam President Roy Evans asked him to create it from a new Bantam saloon. Sure, said Alex. The next day Evans said he’d changed his mind. “Too late,” replied Alex, “I’ve already cut the top off.” He drove the prototype to the Bantam works in Butler, Pennsylvania. Added to the line, it sold well.

Briggs and the Thunderbolt

Tremulis wandered to Detroit and the Briggs Body Company, where opportunity knocked. Chrysler asked Briggs for new designs to replace its aging fleet of post-Airflow clunkers. “Styling at Briggs was almost a ‘good will’ department,” Alex recalled. “We could offer clients a fresh viewpoint, free from engineering restrictions, dedicated solely to ideas.” The result was a pair of exotic dream cars. The Newport dual-cowl phaeton was styled by Ralph Roberts, formerly of LeBaron. The Thunderbolt was styled by young Tremulis. Chrysler built six of each.

Alex originally proposed the names Golden Arrow and Thunderbolt, after two British Land Speed Record cars. His promotional slogan was “The Measured Mile Creates a New Motor Car.” Sir Henry Segrave’s Golden Arrow had set the record 231.5 mph in 1928. Captain George Eyston’s Thunderbolt set it twice, at 312.0 and 357.5 mph in 1937-38. At the last minute, however, Chrysler changed “Golden Arrow” to “Newport.”

The Thunderbolt had the world’s first retractable hardtop, long and low on a 127-inch wheelbase. Its broad single seat could accommodate four passengers. Alex created the smooth envelope body, hidden headlamps; Budd streamliners inspired the wraparound bright molding. Pushbutton electrics controlled the headlamps, windows, trunk lid and top. The Thunderbolt and Newport were soon wowing crowds at car shows and Chrysler dealerships around the country.

Tremulis believed the two cars “revived streamlining at Chrysler after the failure of the Airflow.” They influenced many later prototypes. The Thunderbolt’s curved corner bumper sections were chrome-plated brass, impractical in mass production. Hidden headlamps appeared on the 1942 DeSoto, but were not revived after the war.

Tremulis in the War

After America’s entry into the Second World War, Tremulis joined the Army Air Corps. A lover of aircraft, he began sketching advanced fighter planes at what is now Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. On a weekend pass to Chicago in 1942, he met Chrisanthie Politis. They married and lived happily ever after.

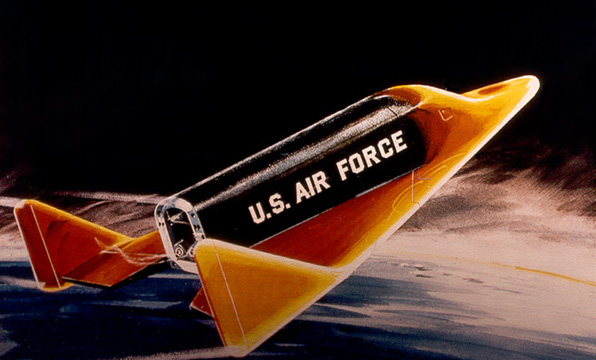

Alex left the USAAC in 1944, but his Air Force connections continued. Between 1957 and 1963 he helped design the Boeing X-20 Dyna Soar, a precursor to the Space Shuttle. The orbiting re-entry vehicle performed aerial reconnaissance, bombing, space rescue, satellite maintenance and intercepting enemy space vehicles. Alex always regretted that NASA canceled the project just after initial construction had begun.

Meeting Tucker

Alex and Chrissie were from Chicago, so they moved back there in 1946. Alex found work with the industrial design firm Tammen and Denison. Among their clients was an energetic promoter with a vision of a ground-breaking car: Preston Tucker. “We met and hit it off right away,” Alex remembered. “He wanted me to be his chief stylist, so he talked T&D into releasing me. Preston could talk the birds out of the trees. When he looked at you with those soft brown eyes, you were hooked.” For a thirty-two-year-old stylists, it seemed the chance of a lifetime.

One thought on “The Greatness of Alex Tremulis: A Car Designer from Another Era (1)”

Thanks for the history on my Uncle Alex!

Comments are closed.