What Price Tiffany? Ned Jordan and History’s Greatest Car Ad

Jordan: The ethereal chariot

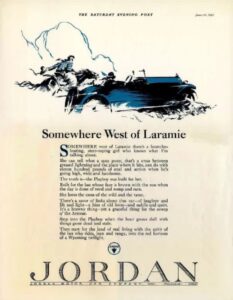

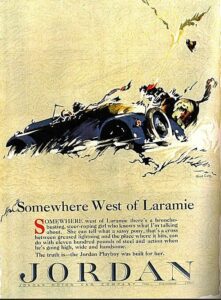

The greatest advertisement in the history of the automobile, “Somewhere West of Laramie,” was written for a medium-priced car during a dull era and a duller economy, by a cocky little 40-year-old redhead, Edward S. Jordan.

The Jordan was what we then called an “assembled automobile.” Outside suppliers provided its components—albeit of high quality. Ned Jordan explained the idea in a 1945 monograph, The Inside Story of Adam and Eve:

We were pioneers of a new technique in assembly production, custom style sales and advertising…had only one air compressor to power the assembly line…bought only the finest component parts from the most experienced quality parts makers…designed a chassis for those parts that possessed the most ideal weight distribution yet attained. Then we “dolled them up” just as every good car is dressed today.

Not many care about the cars, though a few hundred survive, and from the mid-1920s they were pretty snappy numbers. Some Jordans are even designated “Classics” by the Classic Car Club of America. What mattered was the magic Ned Jordan wove around them: the most romantic (and often risqué) prose ever expended on an automobile. After Packard, Jordans were the first cars seriously promoted to women.

Ned, Kate and John Henry

Edward S. Jordan was born in 1882, in the lumber town of Merrill, Wisconsin, the only boy in a family of six. He was talkative, brash and a bit rude. He had heaps of determination but little money. Ned wore white spats and bright ties and well-tailored suits, but he wasn’t a huckster. He had style—like the cars he built and the words he wrote.

Working his way through college as a newspaper reporter, Jordan discovered his talent for words. Two people provided his sales and advertising know-how: his mother and John Henry Patterson.

Kate Jordan taught Ned about people—”vital,” he wrote, “to all good advertising. She never used the word ‘psychology.’ But she did say that ‘Tilly Hart wound up at the Devil Creek place because she valued silk stockings above her immortal soul.’ And: ‘Mrs. Webster’s Fred has been raised to $5 a day, so she is trying to learn to like olives and read a book.’”

J.H. Patterson was President of the Google of its day: National Cash Register (NCR). It commanded 97% of the business machine market. John Henry hired Ned Jordan out of college, advising him: “Do at least one thing, however simple it may be, a little better than anybody else. Then go out and make your prospective buyer feel as you do about your product. Just remember, a man is only half-sold until his wife is sold.”

“How’d you get fired?”

Ned married one of the Jeffery girls from Kenosha, which put him into the car business. In 1907 he arrived at Jeffery, freshly fired by Patterson: “Any man fired by John H. is worth from $10,000 a year on up to any business. ‘How’d you get fired?’ was the lodge greeting among old NCR men.”

Jeffery hired Jordan as advertising manager, and he was general sales manager before he was 30. “Confidentially,” he said, “I was the one who encouraged Jeffery to sell to Nash, because they knew I was then planning to organize the Jordan Company. By now, Ned had seen the light:

Cars are too dull and drab. People dress smartly, so why should they drive prosaic looking automobiles? I think people are growing sick and tired of ordinary cars. Great careening arks of bulk and extravagance. The world is too full of the commonplace.

Do you know why Henry Ford is the greatest man in the automobile industry? All the other early manufacturers built cars in which they like to ride themselves. He was the first to build a car for the other fellow.

Jordan told dealers he’d emphasize “appearance, style, comfort and convenience, power in reserve, durable service and quality…. Thousands of Dodge and Buick owners aspire to own a better car. If you can sell 25 Jordans, you stand a good chance of making 45% on your investment.”

“We were a bunch of bright kids,” he reflected. “I was 33, the rest 28, when we started. We did make a lot of money, awfully fast. The Idea was almost too gol-darned good.”

“The girl who loves to swim and paddle and shoot”

In Detroit, chief engineer Russell Begg developed a body to wrap around a six-cylinder Continental engine. They had no factory, so Ned paid $50,000 for a five-acre site in Cleveland. By mid-1915, Jordans were coming off the line.

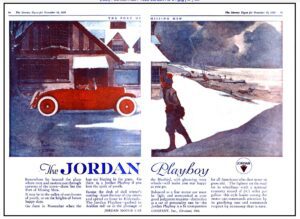

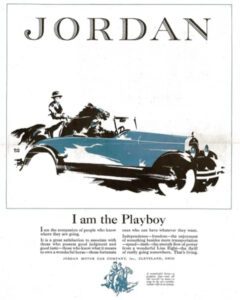

Jordan recognized the closed car market and added a sedan and coupe in 1917. By 1918 he was building 5000 cars a year—impressive for a small independent. Plant space was expanded, bonuses paid. In April 1919 came the first Jordan Playboy. Hardly anyone noticed—but Ned was just getting started. His next inspiration was named Eleanor:

Dancing one night at the Mayfield Country Club, Cleveland, with a real outdoor girl, Eleanor Borton. “Why don’t you build a swanky roadster for the girl who loves to swim and paddle and shoot, and for the boy who loves the roar of the cutout?” asked Eleanor. “Girl, you’ve given me an idea worth a million dollars! Thanks for the best dance I’ve ever had. I’m leaving for New York.”

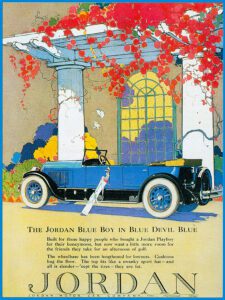

Next day…a custom body designer permitted a private peek at a roadster designed for Billie Burke as a present from her fiancé, Florenz Ziegfeld. Burglary ensues! The design, very simple, sketched out on an envelope in an inside pocket. Result: the Playboy (a name adapted from Sygne’s Playboy of the Western World ) became a part of the American language. A dashing, debonaire Something in Copenhagen blue.

We built one just for the fun of doing it. Stepped on it, and the dogs barked and the chickens ran. It’s a shame to call it a roadster, so full is this brawny, graceful thing with the vigor of boyhood and morning.

“The Port of Missing Men”

There was a certain risqué character to Jordan ads. Though Ned specialized in wheedling women buyers, he also had a crack at the male market. After all, what better customers for a car called the Playboy?

So in 1920, well before “Somewhere West of Laramie,” he tempted the propriety watchdogs of a century ago, just as anxious to stifle “offensive” prose as the self-appointed nannies of today’s social media. Let Ned himself tell the story:

The trick was to get the copy to the [Saturday Evening Post] in time to beat the deadline. And [not] to bring the Society for the Suppression of Vice down on our necks. They were squeamish then….

I grabbed a piece of stationery, sketched a lonely roadside inn, marked the building “midnight blue”…big, walloping moon…a couple of stars…one pale red spot of color behind the curtain of one window. Playboy two-passenger roadster parked in front…line for illustration: “The Port of Missing Men.”

A letter from vice headquarters. And the reply: “We regret exceedingly that our recent advertisement has offended your high moral sense. It is evident that we must exercise closer supervision over our art department. Perhaps if the artist had placed the lights in two or more windows…. I assure you that this advertisement will not appear in the Post again.

That was Ned Jordan, the man who put sex appeal on wheels.

Wooing Eve

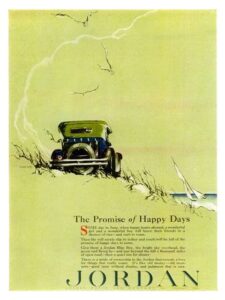

By 1918, women were buying more cars than ever—a development not lost on the canny Jordan. So his ads began appealing directly to them. Flattering and beguiling, they conjured up wanderlust and adventure, appealing to a woman’s taste and style:

Eve walks into the showroom because she’s read an advertisement that is “down her alley.” No injector manifolds or gear reduction talk. No engineering details. That’s all fine and dandy if you’re selling locknuts.

She looks. The color is Burgundy Old Wine, Egyptian Bronze, Ocean Sand grey, Copenhagen blue. The color of the sun, the sky, the grass, her gown. She feels the upholstery material always. It’s Laidlaw—eight dollars per yard. She steps in, grasps the wheel, relaxes on Marshall cushion springs: A position of poise she sees reflected in the mirror in the salesroom. Pictures herself in the darkest window as she drives down the avenue. Her good taste approves. What price Tiffany? she wonders to herself.

The debonaire salesman would say, “Well, madam, you can see this car has so many things that only custom cars have. And we built so few and for a quite limited group of buyers. Let’s see now.… Silvertown Cord tires with two extras, wire wheels, Crane Simplex finish, Waltham clock, Vogue vanity cases. Of course you want this car for your personal use…. We wouldn’t want to deprive your husband of the old car….

“The price is $3475, including the Cordovan leather boot and saddle bag in the tonneau for your personal things. You’ll want that, won’t you?” Oh! the joy of watching a real salesman prove that he’s not just a price-conscious order taker.

Laramie, July 1923

Laramie, July 1923

Ned Jordan spent July 4th, 1923 at his Rhode Island summer home, watching his daughter Jane perform tricks on a salty pony. “That child could ride—well enough to win prizes at rodeos….”

Three days later, on the Overland Limited, bound for San Francisco. A chat, at about dusk, with Mr. Austin, a New York lawyer, in the forward end of the lounge car. We passed some station in Wyoming, too late to catch the sign. Just then a husky Somebody whirled up on a rarin’ cayoose…he, acting as if he’d never seen a Union Pacific train. She reminded me of Jane.

“Where are we now?” I inquired, to make conversation.

“Oh, somewhere west of Laramie,” yawned my companion.

I took an envelope from my pocket, wrote down the phrase, and added, as I looked from the window, “there’s a bronco-busting, steer-roping girl who knows what I’m talking about. She can tell what a sassy pony, that’s a cross between greased lightning and the place where it hits, can do with eleven hundred pounds of steel and action when he’s going high, wide and handsome. The truth is—the Jordan Playboy was built for her….”

Artist Fred Cole provided the perfect artwork of the girl on her horse racing a Jordan Playboy. The job was done.

“My wings are spread…I’ll fly to you”

Imagine how that broadside hit the war-weary public—women especially. Car ads then were filled with paragraphs of specifications. Not Jordan’s. “That was no mundane vehicle of a solid sphere,” Ned recalled. “That car was an ethereal chariot, imbued with the spirit of young romance and old boxing gloves….

The letters poured in. A girl in Ohio wrote: “I don’t want a position with your Company. I just want to meet the man who wrote that advertisement. I am 23, blonde, weight 130. My wings are spread. Just say the word and I’ll fly to you.”

I think the best things are written like that. You write as you feel…or, you compose with an effort, hoping to make others feel. Stephen Foster asked his brother to name a southern river to use in his song…rejected “Peedee” for the name “Suwanee.” Brother knew his geography. Stephen knew rhythm. With the right copy you can get a smile out of the Sphinx.

The best Jordans began with the 1925 Line Eight: 125.5 inches of wheelbase, rakishly low, 74 horsepower, an unprecedented turn of speed, only $1695. Jordan’s best year was 1926: over 11,000 cars, led by the Line Eight Playboy and the senior Great Line Eights.

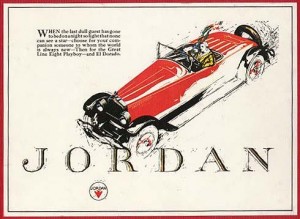

“When the last dull guest has gone…”

Ned predicted a good year in 1927, “but no repeat of ’26.” Then he made a mistake, one often made in the car business. He launched a small car before its time.

The Little Custom expressed Jordan’s traditional goal of lightness, balance, precision and economy. It had chiseled lines, crowned fenders, aluminum radiator, luxurious upholstery, a wicker dash with polished walnut instrument panel. It flopped.

The company ran into the red. “The big volume manufacturers began selling on time payments, financing their distributors,” Jordan complained. “The shadow of 1929 was clearly on the wall. We started to liquidate in 1928, finished in 1931.”

Jordan’s health failed along with his marriage after 1927. His interest waned, though his firm toward the end built its best cars ever. The company went out in style, fielding the ultimate Jordan, the aptly named Model Z. The factory built only 14 (one survives). The 1930-31 models saw no changes, and Jordan had vanished by 1932. Estimates vary, but total production was probably about 70,000.

“Heigh-ho!…for the open road…”

Were Jordans really any good? “If you want to find out, ask one of the owners,” Ned would say. “There are a few on the road yet. I know one that has gone 400,000 miles. The owner got a lump in his throat when I told him my name. He loves that car—and it’s four times as old as my daughter Kate.”

Ned Jordan never reentered the car business. He remarried in 1940 and joined MacArthur Advertising, where he spun prose for three-dimensional signs in railroad terminals. In the Fifties he enjoyed a comeback. writing a popular column, “Ned Jordan Speaks,” for Automotive News. “I won’t charge you a nickel for my pontifical advice,” he wrote a friend of mine. “It’s always free.”

Jordan died in New York in 1958, the original romancer of the automobile. His “Golden Girl from Somewhere” never aged. Through Ned’s words, she’s still there in our collective memory:

When the Spring is on the mountain and the day is at the door…leave the hot pavements of the town. Then heigh-ho!…for the open road. Five roads to the right, five roads to the left…and you’ll greet the rising sun in El Dorado.

***

Letters from readers

This article was originally published in four parts in 2011. So as not to lose them, I reprise comments received at that time… RML

Michael Robertson: Thank you, Mr. Jordan, for that wonderful advertisement. I wonder what happened to the 130 pound blonde. I experienced a Freudian Slip when I read “My wings are spread.” RML: Tut-tut, Mr. Robertson. Somewhere West of Laramie, there’s a silver-haired woman who knows what you’re talking about…

Tim Lyman: Was there an association between Jordan and Cole automobiles? In what old magazines should I look for Jordan ads? RML: I don’t think there was one. Cole was in Indianapolis, Jordan in Cleveland. Fred Cole was the artist of the famous “Somewhere West of Laramie” ad, but I don’t think he had a connection to Cole automobiles. Look for ’20s copies of The Literary Digest, Vogue and Saturday Evening Post, among others. Search the web and eBay for Jordan car ads.

Ike: Fascinating story! Thank you! RML: Labor of love, Ike.

2 thoughts on “What Price Tiffany? Ned Jordan and History’s Greatest Car Ad”

How many versions of Somewhere West . . . were there? Was the ad run in the Post more than once?

–

There was only one version of the text, but it ran several times in the Post. Sorry, I don’t have a list. -RML

Superb article, surpassed only by the artwork. That Jordan Blue Boy ad must have stood out like a beacon in the 1920s. Packard had several color ads in the early ’20s—but nothing like that! Artist Fred Cole was featured in an article by Gwil Griffiths in The Packard Cormorant #35 (Summer 1984). Cole produced four ads for the 1931 through 1934 Packards. Packed away in my loft is my collection of Automobile Quarterly, so I am going by memory here…Was it you or Beverly Rae Kimes who wrote “Ned Jordan: The Spell He Wove / The Cars He Built”?

–

Thanks, Stuart. Good memory! It was AQ, Vol. 13, No. 2, second quarter 1975, by Tim Howley (The Spell) and me (the cars). Bev Kimes was editor then. She always loved Jordans. —RML

Comments are closed.