The Language: Canceling Clichés and Issues over “Issues”

“Let us have an end of such phrases as these: ‘It is also of importance to bear in mind the following considerations….’ Or: ‘Consideration should be given to the possibility of carrying into effect.’ Most of these woolly phrases are mere padding, which can be left out altogether or replaced by a single word. Let us not shrink from using the short expressive phrases, even if it is conversational.” —Winston S. Churchill “to my colleagues and their staffs,” 9 August 1940.

Canceling Clichés

Commentator Bill O’Reilly proposes a new Cancel Culture for a collection of jargon that Churchill would define as “grimaces.” A cliché, he says, is “a phrase or opinion that is overused and lacks original thought.” Good on Bill, and we applaud his nominations for grimaces we never need to hear again. He forgot “issues,” but it’s not a bad list….

“Circle back”: A banal term often used in presidential briefings

“Here’s the deal”: President Biden’s favorite.

“Deep Dive” (used interchangeably with “From 30,000 feet”): Supposed to refer to your detailed opinion (from the worm’s eye, or from on high). Often encountered in the media—always painful.

“Perfect Storm”: Description of the 2024 U.S. election.

“At the end of the day”: O’Reilly: “What day? Thursday? Stop it! Athletes in particular.”

“It is what it is.” Dreadful.

“Give a listen.” Used in absence of an intro. Beloved by Brett Baier on Fox. [I added that one.]

“I’ll be honest”: This implies that most of the time you’re not honest.

“Sorry, not sorry”: O’Reilly: “Sorry, you are a moron.”

“Game changer”: All-purpose slough off.

“We’ll see”: When you don’t know what you’ll see.

“The new normal”: Means you don’t know what is normal.

“Slam dunk”: “The most over-used phrase in the language.”

“By the way”: “What way? Where? Stop!”

Why has this jargon so permeated the media? One of the culprits, O’Reilly suggests, “is the collapsing public education system. In New York City, taxpayers spend $31,000 per student per year and many students cannot speak proper English.”

Some issues over “issues”

O’Reilly is targeting brief phrases or single words. Somewhat longer “wooly phrases” have also been creeping into our language—for a long time. For decades now, we have substituted politically correct fad-phrases for long-understood words in everyday language.

My pet favorite is the word “issues,” as substituted for “problems” or “difficulties.” The idea is that we must not be judgmental (another popular favorite) about our troubles, because our troubles may be right. After all, a mugger with a knife is only expressing his issues.

No. Issues are subjects on which there are different points of view. Most of the time, when we say we have “issues,” we mean to say we have ”problems.” But we want to be nice.

This word-substitution is subconsciously catching, because we all want to use hip forms of speech. If editors don’t watch out, even we fall for it. I recently had to stop myself from saying that I had “issues” with certain fanatics who are trying to kill us. What I had, of course, are “problems,” if not “violent objections.”

“Reaching out”

Then there is “reaching out.” One doesn’t contact someone any more. One “reaches out.” The theology behind that is that “contact” suggests you are “demanding” something. Like the courtesy of a reply, which might be “offensive.” By “reaching out,” you become a supplicant, making a tentative plea that will not offend anyone. Your contact doesn’t really have to answer. (And have you noticed? Quite a few of them don’t.)

One might expect anyone familiar with the life of Winston Churchill to tilt toward traditional language, and one would be right. I don’t care what you think about the wars in Ukraine or Syria or Gaza, economic policy, immigration, religion, global warming, or the leaders of countries. All those are legitimate, er, issues, over which reasonable people may disagree.

Real issues

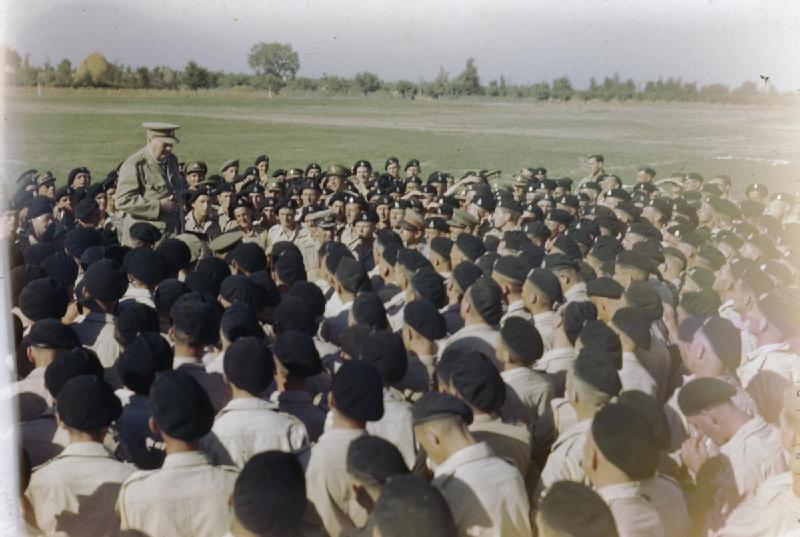

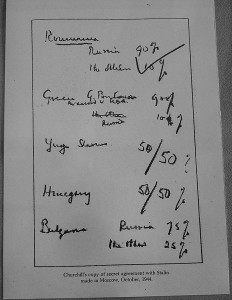

Issues (in the legitimate meaning of the word) came up at a scholarly panel over the “percentages” agreement. That was the “spheres of influence” agreement in eastern Europe, between Churchill and Stalin at the “Tolstoy” conference in October 1944. That, it was said at the time, proved that Churchill and Britain were no different than Stalin and Russia. Both sides had identical objectives, i.e., their own national interests. But British interests in Greece involved things like the ouzo concession for Harrods, or maybe Greek support for British Mediterranean policy. Soviet interest in Romania were everything Romania had or could produce.

There are those who would have us believe that the Western democracies are no better than Nazis, Soviets, or Islamofascists. We hear the line quite often nowadays. A High Personage will suggest that the displacement of Palestinians after the 1948 Arab-Israeli war was morally equivalent to the Holocaust.

Right, that’s an issue. Why then are there no “issues” over other forced migrations since 1945? Such as sixteen million Sikhs, Muslims and Hindus in India; 800,000 Jews from Arabia; Crimean Tatars, Chechens, Ingush and Balkars “relocated” by Stalin; Japanese and Korean Kuril and Sakhalin islanders; or Italians in Istria? What about three million ethnic Germans in Silesia and the Sudetenland? Or, more recently, the Greeks of Turkey and Cyprus and the Vietnamese boat people?

“Many of these refugees built new lives and a higher standard of living than in the lands they left,” wrote Andrew Roberts. “None are today actively demanding the right to murder people who have now lived in their former lands for over seven decades.” Sorry. I digress.

A shade of difference

Celebrate Mr. O’Reilly’s modest proposal: Avoid fashionable filters and fad-words in language. “Short words are best,” Churchill said, “and the old words, when short, are best of all.” His thoughts and deeds, however antique they may sound today, still represent concepts we can understand. No issues there.

Related reading

“Churchill on Jargon: The Language as We Mangle It,” 2019.

“Churchill on Jargon: “Let Us Have an End to This Grimace,” 2024.

“Athens, 1944: Some Lighter Moments in a Serious Situation,” 2020.

“Churchill, Orwell and 1984.” 2022.

“Churchill’s War Memoirs: Aside from the Story, Simply Great Writing,” 2023.

3 thoughts on “The Language: Canceling Clichés and Issues over “Issues””

Stu Needleman writes: “I don’t think ‘deep dive’ and ‘from 30,000 feet’ are the same. The latter means a high-level look at an ‘issue’ while a ‘deep dive’ is delving into the details.” I agree, although both expressions refer to the same kind of superior people who profess to interpret the news for the vast unwashed multitude.

Spot on! A couple more that I really hate are:

“Let’s unpack that.”

“Kick the can down the road”

“I hear you”

—and one used on me by parents, spouses, bosses whenever (which is not often) I ask for something they have absolutely no intention of agreeing to: “I’ll think about it.”

–

Thanks for reaching out and circling back! -RML

I’ll add one to the list: “no problem.” It bugs us when we say “thank-you” to someone (say a waiter) and the response is “no problem.” I didn’t think it was a problem in the first place. How about a “you’re welcome”?

–

Bingo. “No problem” is another faddish “nice” expression attempting to acknowledge that gee, I’m so glad you weren’t offended in our encounter.” Thanks! -RML

Comments are closed.