Churchill, Orwell and “1984”

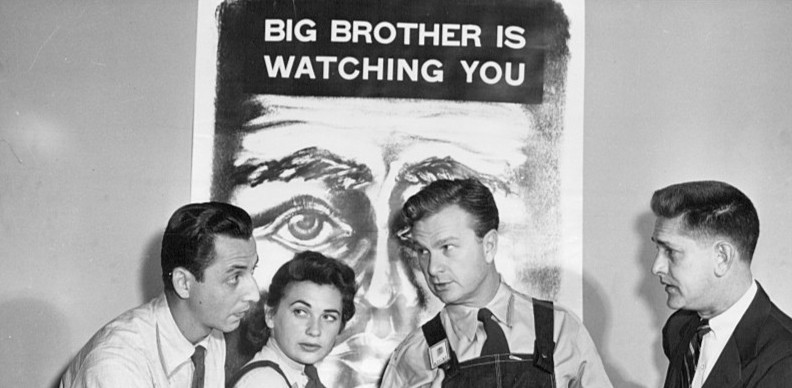

(Update.) George Orwell’s prescient masterpiece 1984 turns 73 years old this year, and is still in the news. Thoughtful people say this is because we are, post-Covid, with government ever increasing its intrusion into our lives, closer to the totalitarian world Orwell imagined than ever.

Some reviewers of 1984 have found the need to take a whack at Churchill. One of those was Robert Harris in The Sunday Times, where he wrote with singular inaccuracy: “Given that only five years [before the book], Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin had divided up the world into ‘zones of influence’ at the Teheran Conference, [Orwell’s] vision did not seem entirely fantastic.”

What is fantastic is where people get such notions. “Zones of influence” came up not at Teheran but at the Moscow (“Tolstoy”) Conference between Churchill and Stalin a year later. It divided influence in former occupied German territories, by then being occupied by the Red Army.

Churchill thought this as an expedient, with final arrangements to be made at a peace conference. Stalin had something more permanent in mind. In any case, it was not “dividing up the world.”

The main result of that meeting was to allow Churchill to save Greece from a communist takeover—temporarily. (Stalin had another go a few years later). And the only reason we even know about the Moscow agreement was because Churchill freely described it in his war memoirs. (See “Athens, 1944.”)

Churchill on Orwell

Of WSC’s opinion of Orwell we know little, except from his doctor Lord Moran’s “diaries.” That was in 1953, during WSC’s second premiership, three years after Orwell’s untimely death at age 46. Churchill told his physician that was reading a “remarkable” novel. He did not, however, mention 1984 in his speeches. Nor, as far as I know, did he allude publicly to Orwell’s oeuvre.

Orwell on Churchill

Sir Fitzroy Maclean once asked Tito, “a most perceptive man, what had struck him most about Winston. Tito replied instantly and I thought it was very clever of him: ‘His humanity. He is so human.’ By this central humanity, and his statesmanship and courage, Churchill did something that not many politicians seem to do nowadays. He caught people’s imagination and won their affection.” (See Fitzroy Maclean, Wit and Wisdom.)

Orwell, like Tito a man of the Left, held exactly the same view. This was noted eloquently by Robert Pilpel, quoting Orwell in Finest Hour 142, Spring 2009:

His writings are more like those of a human being than of a public figure…. And whether or not 1940 was anyone else’s finest hour, it was certainly Churchill’s…. One has to admire in him not only his courage but also a certain largeness and geniality…. The British people have generally rejected his policies, but they have always had a liking for him, as one can see from the tone of the stories told about him….

At the time of the Dunkirk evacuation, for instance, it was rumoured that what he actually said, when recording his speech for broadcast, was: “We will fight on the beaches…we will fight in the streets…we’ll throw bottles at the bastards; it’s about all we’ve got left!” One may assume that this story is untrue, but at the time it was felt that it ought to be true. It was a fitting tribute from ordinary people to the tough and humorous old man whom they would not accept as a peacetime leader [in 1945] but whom in the moment of disaster they felt to be representative of themselves.

“From one giant guardian of our heritage to another”

I’ve always loved Bob Pilpel’s conclusion, redolent of what Winston Churchill truly meant to his contemporaries—of many political persuasions. Some might flatly disagree with him. Some would argue hammers and tongs across the floor of the House of Commons. But underlying it all was a grounding of mutual respect. Pilpel concludes:

Speaking as a considerably less tough and more sentimental old man, I confess that Orwell’s gentle accolade—from one giant guardian of our heritage to another on the opposite end of the political spectrum—always makes my eyes mist over. I offer this confession willingly, even cheerfully, happy in the knowledge that many admirers of Churchill, no matter what their age, may go me one better and shed a tear.