Churchill’s War Memoirs: Aside from the Story, Simply Great Writing

Excerpted from “Trumpets from the Steep: Churchill’s Second World War Memoirs,” an essay for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original article with endnotes and more photos, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, and fill in your email in the box entitled “Stay in touch with us.” Your email address is never given out and remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

The Memoirs: An Appreciation

We were welcomed here like people returning from the Promised Land of Utopia. A million questions…. “What do they really think?” “Do they think us phony?” “Are they on our side?” “Why is the betting going against us?”…. And weaving through the alarms was the conviction of Parliament and the people that Winston must take the helm of our scandalised ship. He must shoulder our hopes and our efforts and imbue us with courage, or the ship would sink. —Lady Diana Cooper, returning from America, March 1940, Trumpets from the Steep, 1960.

*****

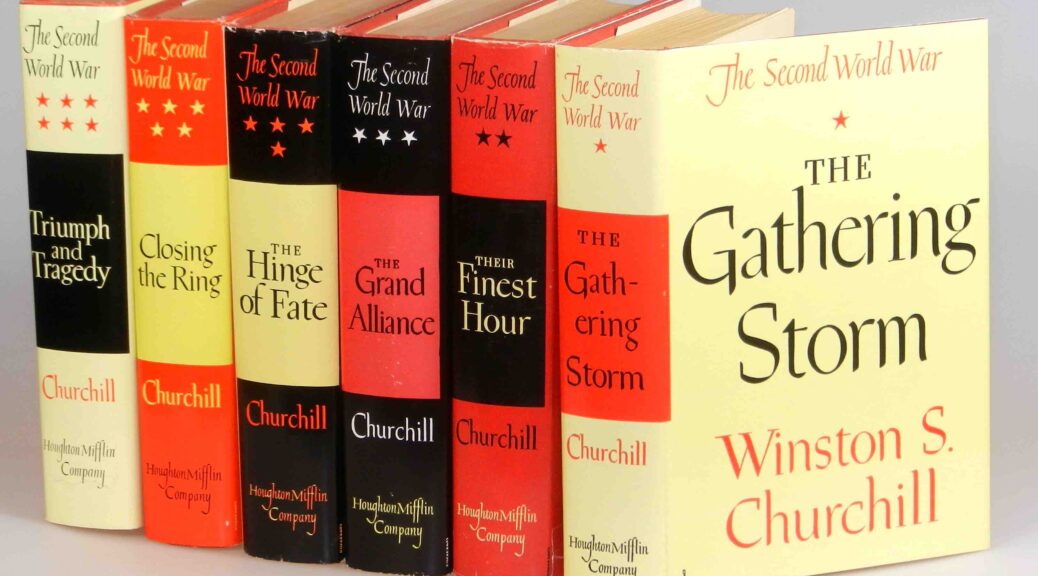

Let us begin by recording the main criticisms of Churchill’s The Second World War. It is not history. Its grandiose prose was inflicted on apathetic readers who only wanted peace and a quiet life. It is biased—the author never puts a foot wrong. He publishes hundreds of his own memoranda and directives—but few replies to them. He moralizes incessantly about dictators and their empires—but not Britain’s. The impact of the war on Britain, the details of Cabinet meetings, are vague. Churchill alone confronts the French, Hitler, the Soviets, the Americans. “Every instance of adversity becomes an occasion for the narrator’s triumph.” Finally, Churchill didn’t write it himself—he relied on a team of researchers, military and political.

In the words of Arthur Balfour, these indictments contain much that is true and much that is trite. “But what’s true is trite, and what’s not trite is not true.”

“This is not history—this is my case”

Professor J.H. Plumb referred to Churchill’s work as A History of the Second World War —and then said it was not history. Churchill himself contributed to the confusion: “…it will be found much better by all Parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history myself.” He also referred to his “history” in letters to Truman and Eisenhower. But it’s a memoir, not a history—like The World Crisis, his volumes on the First World War. There he had explained his approach:

I must therefore at the outset disclaim the position of the historian. It is not for me with my record and special point of view to pronounce a final conclusion. That must be left to others and to other times. But I intend to set forth what I believe to be fair and true; and I present it as a contribution to history of which note should be taken together with other accounts.

Some thought Churchill dissembled and was too modest. John Keegan called The Second World War “a great history” of “monumental quality…extraordinary in its sweep and comprehensiveness, balance and literary effect; extraordinary in the singularity of its point of view; extraordinary as the labour of a man, already old, who still had ahead of him a career large enough to crown most other statesmen’s lives; extraordinary as a contribution to the memorabilia of the English-speaking peoples.”

“Britain was led by a professional writer”

If that seems too positive a view, consider Manfred Weidhorn’s evaluation: “a record of history made rather than written…. No other wartime leader in history has given us a work of two million words written only a few years after the events and filled with messages among world potentates which had so recently been heated and secret. Britain was led by a professional writer.”

As a professional writer wishing to build a legend, goes another refrain, our author ignored or buried unpleasant facts, or twisted them to suit his purpose. I have yet to read a memoir that didn’t. Yet few memoirs are so magnanimous, as illustrated by a principle Churchill adopts in his preface: “Never criticising any measure of war or policy after the event unless I had before expressed publicly or formally my opinion or warning about it.” The effect, Keegan tells us, “is to invest the whole history with those qualities of magnanimity and good will by which he set such store, and the more so as it deals with personalities.”

Intensely personal

So much for the non-trite and non-true. Other criticisms are hardly crippling. That Churchill assigned passages of military and political history to teams of specialists should hardly surprise us. When he began the writing he was over 70, not in the best of health, exhausted after six years of struggle. How many septuagenarians would take on such memoirs without help? Yet Churchill, of course, signed off on every word. He corrected multiple galleys, demanding fresh ones, correcting again, until beyond the last moment, to the exasperation of publishers.

The Second World War is indeed intensely personal, considering the war from Churchill’s angle not Britain’s. He even gave the work its own Moral: “In War: Resolution; In Defeat: Defiance; In Victory: Magnanimity; In Peace: Good Will.” The memoirs are biased; they exaggerate; they commit sins of omissions and a few counterfactuals. All personal memoirs do.

His own spin

Churchill had a right to make his case. Many times in his career he had been second-guessed or misjudged. There was Antwerp and the Dardanelles in the First World War. There was Bolshevism, Irish independence, the General Strike in the 1920s. Then came the India Act, the Abdication, the Spanish Civil War, Mussolini and Hitler. That is a formidable assortment of grist for critics.

During the war Churchill had attacked an ally’s fleet, fired generals, lost battleships, stalled on launching a second front, argued with Roosevelt and Stalin, and carpet-bombed Germany. He felt the need to defend his actions, knowing that very soon he would be second-guessed by postwar critics, former colleagues and historians eager to seize on and emphasize his mistakes. And the mistakes were there.

In fact, “revisionism” had already begun as he wrote the second of six volumes. Churchill confronted it:

In view of the many accounts which are extant and multiplying of my supposed aversion from any kind of large-scale opposed-landing, such as took place in Normandy in 1944, it may be convenient if I make it clear that from the very beginning I provided a great deal of the impulse and authority for creating the immense apparatus and armada for the landing of armour on beaches, without which it is now universally recognised that all such major operations would have been impossible.

Simply great writing

The merits of Churchill’s memoirs eclipse their evident flaws. There is, first, what Robert Pilpel calls “the warm sense of communion,” through which only a great writer can place the reader at his side in the march of events. Those events are conducted like a symphony.

Or if you will allow the risk of hyperbole, consider Manfred Weidhorn’s comparisons of Churchill’s greatest scenes with those of a first class novel:

Such is the eerie sense of déjà vu and ubi sunt upon his return in 1939, as First Lord [of the Admiralty], to Scapa Flow, exactly a quarter of a century after having, at the start of the other world war, paid the same visit during the same season in the same capacity….

The collapse of the venerable and once mighty France and Churchill’s agony are beautifully rendered by the sensuous detail of the old gentlemen industriously carrying French archives on wheelbarrows to bonfires….

Near the end of the work appears one of the greatest scenes of all. On the way to the Potsdam Conference, Churchill flies to Berlin and its “chaos of ruins.” Taken to Hitler’s Chancellery, he walks through its shattered halls for “quite a long time”…. The great duel is over; the victor stands on the site from which so much evil originated…. “We were given the best first-hand accounts available at that time of what had happened in these final scenes.”

Puck’s escape

Amid the pathos, humour bubbles incessantly to the surface, Pilpel writes, “as if Puck had escaped from A Midsummer Night’s Dream and infiltrated Paradise Lost.” Few other memoirs, let alone histories, leaven their wisdom with such merry wit.

There is Churchill’s famous desert conference with his Generals, “in a tent full of flies and important personages.” We read his courtly letter to the Japanese Ambassador, signed “your obedient servant,” announcing “with highest consideration” that a state of war exists between Britain and Japan. “When you have to kill a man,” he adds, “it costs nothing to be polite.”

All this levity “somehow sits well with the cataclysmic and lugubrious matter of the story,” Weidhorn adds, “for Churchill does not allow the humor to take the sting out of events or reduce war to a mere game. He simply refuses to overlook the light side…. Such a tone, markedly different from the histrionics of the other side, may well be a secret of survival. As Shaw said, he who laughs lasts.”

Telegrams, directives, harangues

Churchill also adds lengthy appendices of personal communications and directives to military and civilian officials. Here again he has been accused of bias, selectivity and an air of infallibility. Some of the messages were trivial—even unworthy of him. But in the main they had a powerful effect: they kept everyone’s eyes on the prize.

Eliot A. Cohen has described a vivid example of one of these, in volume 3, The Grand Alliance. It followed the invasion exercise called VICTOR, in January 1941, which presupposed that the Germans landed five divisions on the Norfolk coast and established a beachhead. Churchill wrote its commander, General Alan Brooke:

I presume the details of this remarkable feat have been worked out by the Staff concerned. Let me see them. For instance, how many ships and transports carried these five Divisions? How many Armoured vehicles did they comprise? How many motor lorries, how many guns, how much ammunition, how many men, how many tons of stores, how far did they advance in the first 48 hours, how many men and vehicles were assumed to have landed in the first 12 hours, what percentage of loss were they debited with?

What happened to the transports and store-ships while the first 48 hours of fighting were going on? Had they completed emptying their cargoes, or were they still lying in shore off the point protected by superior enemy daylight Fighter formations? How many Fighter airplanes did the enemy have to employ, if so, to cover the landing places?… I should be very glad if the same officers would work out a scheme for our landing an exactly similar force on the French coast at the same extreme range of our Fighter protection and assuming that the Germans have naval superiority in the Channel….

* * *

Brooke gamely replied, Churchill rebutted, and the debate went on until it finally petered out in May. What is its significance? Professor Cohen explains:

It is noteworthy, first, that the commander in charge of the exercise, Brooke, stood up to Churchill and not only did not suffer by it, but ultimately gained promotion to the post of Chief of the Imperial General Staff and Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee. But more important is Churchill’s observation that “It is of course quite reasonable for assumptions of this character to be made as a foundation for a military exercise. It would be indeed a darkening counsel to make them the foundation of serious military thought.”

By no means did Churchill always have it right, but he often caught his military staff when they had it wrong. Churchill exercised one of his most important functions as war leader by holding their calculations and assertions up to the standards of a massive common sense, informed by wide reading and experience at war.

“Trumpets from the steep”

Space is running out, and I haven’t told you the half of it. The memoirs remind us of Trumpets from the Steep, Diana Cooper’s deathless title (from Wordsworth). The Second World War is indeed a trumpet call—from heights the reader might not otherwise glimpse. A prose epic like The River War and Marlborough, it belongs among the first rank of Churchill’s books. Flaws and all, it is indispensable reading for anyone who seeks understanding of the war that made us what we are today. As Manfred Weidhorn concludes, “this is not just a unique revelation of the exercise of power from atop an empire in duress, but also one of the fascinating products of the human spirit, both as an expression of a personality and as a somewhat anomalous epic tale filled with the depravities, miseries and glories of man.”

Bibliography: Books on the Book

Arranged chronologically: All of these works concentrate in part or whole on Churchill memoirs, often disputing them on specific points. For notes, editions and links to reviews see my Annotated Bibliography, Hillsdale College Churchill Project, 2021. Look for copies on Bookfinder.com or Amazon.

Fabre-Luce, Alfred. La Fumée d’un Cigare [The Smoke of a Cigar]. Paris: L’Élan, 1949, 246 pp., softbound, text in French; an Italian edition was also published.

Kwasniewski, Tadeus. An Open Letter of a Chicago Waiter to Winston Churchill. Chicago, privately published by the author, 1950, 20 pp., softbound. On the half-title: “Let’s Face the Truth, Mr. Churchill.”

Neilson, Francis. The Churchill Legend. Appleton, Wis.: C. C. Nelson Publishing Co., 1954, 470 pp. Republished as The Churchill Legend: Churchill as Fraud, Fakir and Warmonger, Brooklyn, N.Y.: Revisionist Press, 1979. Also listed as Churchill’s War Memoirs, 1979.

J.H. Plumb, “The Historian,” in A.J.P. Taylor, ed., Churchill: Four Faces and the Man (London: Allen Lane, 1960); Churchill Revised. New York: Dial Press, 1969, 274 pp.

Vicuñia, Alejandro. Winston Churchill a través de sus Memorias [through His Memoirs]. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Universidad Catôlica, 1961, 398 pp., text in Spanish.

Graebner, Walter. My Dear Mr. Churchill. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; London: Michael Joseph, 1965, 128 pp. Translations: German, Finnish, Norwegian.

Ashley, Maurice. Churchill as Historian. London: Secker and Warburg, 1968, 246 pp.

Weidhorn, Manfred. Sword and Pen: A Survey of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill. Albuquerque, N.M.: University of New Mexico Press, 1974, 278 pp.

Weidhorn, Manfred. Sir Winston Churchill. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1979, 174 pp. “Twayne’s English Author” series.

***

Alldritt, Keith. Churchill the Writer: His Life as Man of Letters. London: Hutchinson, Random Century Group, 1992, 168 pp.

Woods, Frederick. Artillery of Words: The Writings of Sir Winston Churchill. London: Leo Cooper Pen and Sword Books, 1992, 184 pp.

Gilbert, Martin. Winston Churchill and Emery Reves: Correspondence 1937-1964. Austin, Tex.: University of Texas Press, 1997, 398 pp.

Valiunas, Algis. Churchill’s Military Histories: A Rhetorical Study. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001, 192 pp.

Reynolds, David. In Command of History: How Churchill Waged the War and Wrote His Way to Immortality. London: Allen Lane, 2004, 600 pp.

Rose, Jonathan. The Literary Churchill: Author, Reader, Actor. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014, 528 pp.

Allport, Alan. Britain at Bay: The Epic Story of the Second World War, 1938-1941. New York: Knopf, 2020, 608 pp.

One thought on “Churchill’s War Memoirs: Aside from the Story, Simply Great Writing”

As Churchill put it only after his uninterrupted achievement of much literary success to an acquaintance of his in the year 1946, “If I had to make my literary will and my literary acknowledgements, I should have to own that I owe more to Macaulay than to any other English writer.” Thank you, Mr Langworth, for sharing characteristically an essay that is going to be a pleasure even to reread.

–

Thanks for the kind words. —RL

Comments are closed.