Winston Churchill on War, Part 3: Anthony Montague Browne

3. Ruminations with Anthony (concluded from part 2)

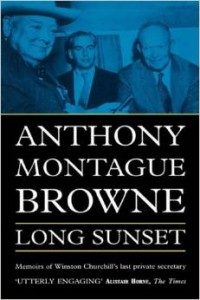

Sir Anthony Montague Browne KCMG CBE DFC (1923-2013) was an RAF fighter pilot and a diplomat who gave up a promising Foreign Office career to serve as Churchill’s private secretary from 1952 to 1965. His essential and poignant memoir, Long Sunset, is available in various formats.

For 20 years beginning 1983 I had the privilege of several long visits with AMB. (He had a score of WSC’s books, all finely bound and personally inscribed. “What do you think of them?” he smiled. “Well,” I said, you’ve made a fairly good start.”)

We sometimes pondered Sir Winston’s late-life despondency. “He’d made a deep study of history,” Anthony said. “And he had an extreme sensitivity to the winds and crosscurrents of world situations.”

I had the greatest respect for Anthony’s opinions from so unique a vantage point, and have quoted those words often. But in considering Churchill’s views on the great issues of peace and war, it is always appropriate to have Anthony’s fuller thoughts.

“Peace does not sit untroubled…”

Churchill was not always upbeat about the ability of humankind to save itself. A hint of future forebodings came in Canada while he was still prime minister:

What is the scene which unfolds before us tonight? It is certainly not what we had hoped to find after all our enemies had surrendered unconditionally and the great world instrument of the United Nations had been set up to make sure that the wars were ended. It is certainly not that. Peace does not sit untroubled in her vineyard. —Winston S. Churchill, 14 January 1952, Chateau Laurier, Ottawa

“Cureless folly done and said…”

His morose thoughts multiplied. During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 he murmured, “we’re all going to be blown up.” Toward the end of his life, the old lion who had implored, “Never Despair,” was gripped by melancholy. His despondence has been noted in varying degrees by critics and champions, historians and analysts, family and contemporaries. What was at the root of it? Anthony reflected:

I think that towards the end of his life his prophetic power was an unhappiness to him. He saw all too clearly what was happening to the civilised world, and to the stern values that stand out so clearly in his life’s work…. He used to quote this sad verse of Housman‘s: “Cureless folly done and said, and the lovely way that led, to the slimepit and the mire, and the everlasting fire.”

I tried to rally him. I spoke of the extraordinary life he had enjoyed, culminating in the fact that at the end, with all he had said and done, he was almost universally popular and admired. When he received the Charlemagne Prize in Germany in 1956, as he drove through the streets of Aachen and Bonn, he was cheered. It astonished him. After all, it was not very long after the end of the war. I referred to that, to his Nobel Prize for Literature, the vast scope of his activities. How, I concluded, could he be so downcast, when he had achieved so much?

I noted his reply verbatim, and he said the same thing on other occasions: “Yes, I worked very hard all my life, and I have achieved a great deal—in the end to achieve nothing.”

Triumph and Tragedy

In 1985 I offered Anthony two reasons why Sir Winston might have felt that way. The first was the realization, probably as early as the Teheran Conference, that he had fought down one monster only to create another, and later that the settled peace he strove for had never materialized. The second was that the English-Speaking Peoples never forged the close relationship on which he placed so much hope.

Anthony’s reply did not come right away. He saved it for a speech he made at a dinner in his honor at the Savoy, later that year:

I think that is a very incisive view. I do indeed believe that the lack of true cooperation between the three great powers had been a terrible and increasing disappointment to him, going back as far as Teheran and Yalta. At that time I was not with him, but this is certainly the impression he gave me in his later years.

I do not think in his heart of hearts that he ever expected anything very different from the Soviet Union, though he had hopes—dismally unfulfilled—of a change of heart after victory. But the euphoria of the early relationship with President Roosevelt during the first years of the war was gradually to die away, as the American administration believed that it could do business with “Uncle Joe.” Some business.

The so-called “special relationship” with the United States was largely of British making, and something of an illusion even from the very start. It was not for nothing that Winston Churchill called the last volume of his war memoirs Triumph and Tragedy.