Reflections on the Birthday of George Washington

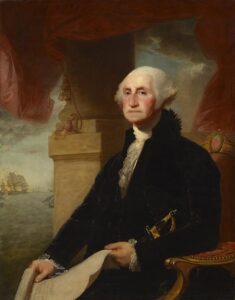

George Washington as President

Disinterested and courageous, far-sighted and patient, aloof yet direct in manner, inflexible once his mind was made up, George Washington possessed the gifts of character for which the situation called. He was reluctant to accept office. Nothing would have pleased him more than to remain in equable but active retirement at Mount Vernon, improving the husbandry of his estate.

But, as always, he answered the summons of duty, Gouverneur Morris was right when he emphatically wrote to him, “The exercise of authority depends on personal character. Your cool, steady temper is indispensably necessary to give firm and manly tone to the new Government.”

There was much confusion and discussion on titles and precedence, which aroused the mocking laughter of critics. But the prestige of Washington lent dignity to the new, untried office. —Winston S. Churchill, The Age of Revolution (1957), 260

It is still Washington’s Birthday

Washington’s Birthday, February 22nd, has been celebrated since 1968 on the third Monday of February. It was NOT replaced by President’s Day. The latter name more or less oozed forward through political and commercial influences in the 1980s. But George Washington’s Birthday is still on the books as a Federal holiday. (Lincoln’s Birthday is not, though four states still celebrate it.)

The ostensible reason for a President’s Day was to make room for Martin Luther King Day, That was fine, but the other two should be reestablished. What difference does it make if we take an extra day off a year? We don’t need to celebrate Millard Fillmore, James Buchanan, Andrew Johnson, and several rather more recent forgettable presidents. (Which, in the George Washington spirit of bipartisanship, let’s not bother to name.)

Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich has posted a thoughtful consideration of George Washington for his birthday, 22 February. It is not the equal of Churchill’s tributes, but nevertheless worth considering. Often in his podcasts, the Speaker acts as a thoughtful sage. What he offers on Washington’s Farewell Address is a reminder that its message and words of caution could have written yesterday. Churchill, writing in the 1950s, also saw that clearly.

Churchill on the Farewell Address

Churchill’s take was not what his admirers might have expected. A confirmed internationalist, with unshakable confidence in Anglo-American partnership, he seemed unlikely to endorse an essentially isolationist view.

Of course Washington was writing in 1796, long before the horrors of 1914 and 1940. So Churchill’s description of the Farewell Address was scrupulously uncritical:

This document is one of the most celebrated in American history. It is an eloquent plea for union, a warning against “the baneful effects of the Spirit of Party.” It is also an exposition of the doctrine of isolation as the true future American policy.

“Europe has a set of primary interests, which to us have none, or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies, the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence therefore it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves by artificial ties in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics or the ordinary combinations and collisions of her friendships or enmities.

“Our detached and distant situation invites us to pursue a different course…. ’Tis our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world…. Taking care always to keep ourselves, by suitable establishments, in a respectable defensive posture, we may safely trust to temporary alliances for extraordinary emergencies.” —WSC, The Age of Revolution, 346-47.

“The just pride of Patriotism”

Speaker Gingrich chose other passages from Washington’s Farewell which have a more current application. Consider GW’s plea for patriotism, a nation without hyphenated-Americans, united around a proposition, not a monarch.** That was unique at the time. It is now somewhat more widespread. Washington wrote:

The unity of Government, which constitutes you one people, is also now dear to you. It is justly so; for it is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquillity at home, your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very Liberty, which you so highly prize, that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national Union….

For this you have every inducement of sympathy and interest. Citizens, by birth or choice, of a common country, that country has a right to concentrate your affections. The name of American, which belongs to you, in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of Patriotism, more than any appellation derived from local discriminations. With slight shades of difference, you have the same religion, manners, habits, and political principles. You have in a common cause fought and triumphed together; the Independence and Liberty you possess are the work of joint counsels, and joint efforts, of common dangers, sufferings, and successes….

However combinations or associations of the above description may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people, and to usurp for themselves the reins of government; destroying afterwards the very engines, which have lifted them to unjust dominion.

“The enterprises of faction”

The First President, Mr. Gingrich adds, would have abhorred both the riots of summer 2020 and of 6 January 2021. To George Washington the rule of law and rights of property, public or private, were sacrosanct:

It is requisite, not only that you steadily discountenance irregular oppositions to its acknowledged authority, but also that you resist with care the spirit of innovation upon its principles, however specious the pretexts…. remember, especially, that, for the efficient management of our common interests, in a country so extensive as ours, a government of as much vigor as is consistent with the perfect security of liberty is indispensable….

It is, indeed, little else than a name, where the government is too feeble to withstand the enterprises of faction, to confine each member of the society within the limits prescribed by the laws, and to maintain all in the secure and tranquil enjoyment of the rights of person and property.

“Riot and insurrection…sharpened by the spirit of revenge”

Washington feared what is now called Balkanization—a nation dissolving into interest groups. He was aware that unity is fragile, quickly diminished by tyrants and demagogues. In modern times we’ve had plenty of examples. Mao, Hitler, Stalin, Kim: the list goes on. The First President foresaw them all:

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism.

The disorders and miseries which result, gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of Public Liberty.

Washington didn’t regard that as a certainty for America, but he warned against it:

Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind, (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight), the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

It serves always to distract the Public Councils, and enfeeble the Public Administration. It agitates the Community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms; kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection; opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.

The end of the beginning

George Washington holds one of the proudest titles that history can bestow. He was the Father of his Nation. Almost alone his staunchness in the War of Independence held the American colonies to their united purpose.

His services after victory had been won were no less great…. firmness and example while first President restrained the violence of faction and postponed a national schism for 60 years. His character and influence steadied the dangerous leanings of Americans to take sides against Britain or France.

He filled his office with dignity and inspired his administration with much of his own wisdom. To his terms as President are due the smooth organisation of the Federal Government, the establishment of national credit, and the foundation of a foreign policy. By refusing to stand for a third term he set a tradition in American politics which has only been departed from by President Franklin Roosevelt in the Second World War.

For two years, Churchill concludes,

Washington lived quietly at his country seat on the Potomac, riding round his plantations, as he had long wished to do. Amid the snows of the last days of the 18th century he took to his bed. On the evening of December 14, 1799, he turned to the physician at his side, murmuring, “Doctor, I die hard, but I am not afraid to go.” Soon afterwards he passed away. —WSC, The Age of Revolution, 347-48

Endnote

** Professor Allen Guelzo, in a brilliant podcast on Washington with Douglas Murray (see below), eloquently defines the the uniqueness of the American founding:

Americans need their history and we argue about it a great deal, and we do that because we don’t have an ethnicity. We don’t have a national religion, we don’t have a national language, we don’t have something that you can point to from centuries back….

Americans are organized around a proposition, as Lincoln said at Gettysburg, that all men are created equal. How do you found nation based on a proposition? In the 1780s and 1790s, people in Europe rolled around laughing at the idea. How could you have a nation built solely on a commitment to a series of propositions based on the Declaration and the Constitution? And yet that is what we are….

We are really committed to these propositions, and so we hold ourselves to a very strict and demanding standard. We don’t live up perfectly to that standard, and that always creates dissonance…. [But if] Americans are a people created not by race or ethnicity or language or religion but by their allegiance to a proposition, then our history is the only thing we have which gives us the stories we tell about ourselves, about Washington and Lincoln and our founding.

Further Reading

George Washington: His Farewell Address, published 19 September 1796.

D. Craig Horn, “Ties That Bind, Part 1, George Washington,” Hillsdale College Churchill Project, 2022.

Audio

Douglas Murray’s Uncancelled History, Episode 5: Washington, with Professor Allen Guelzo, 2022.

Newt Gingrich, “Washington’s Farewell Address,” 20 February 2022.

One thought on “Reflections on the Birthday of George Washington”

Bravo RL. If you have not yet read it, I highly recommend Cincinnatus, George Washington and the Enlightenment: Images of Power in Early America, by Garry Wills (1984).

Comments are closed.