Winston Churchill, Magnanimity and the “Feeble-Minded,” Part 2

Continued from Part 1…

Youthful discretions

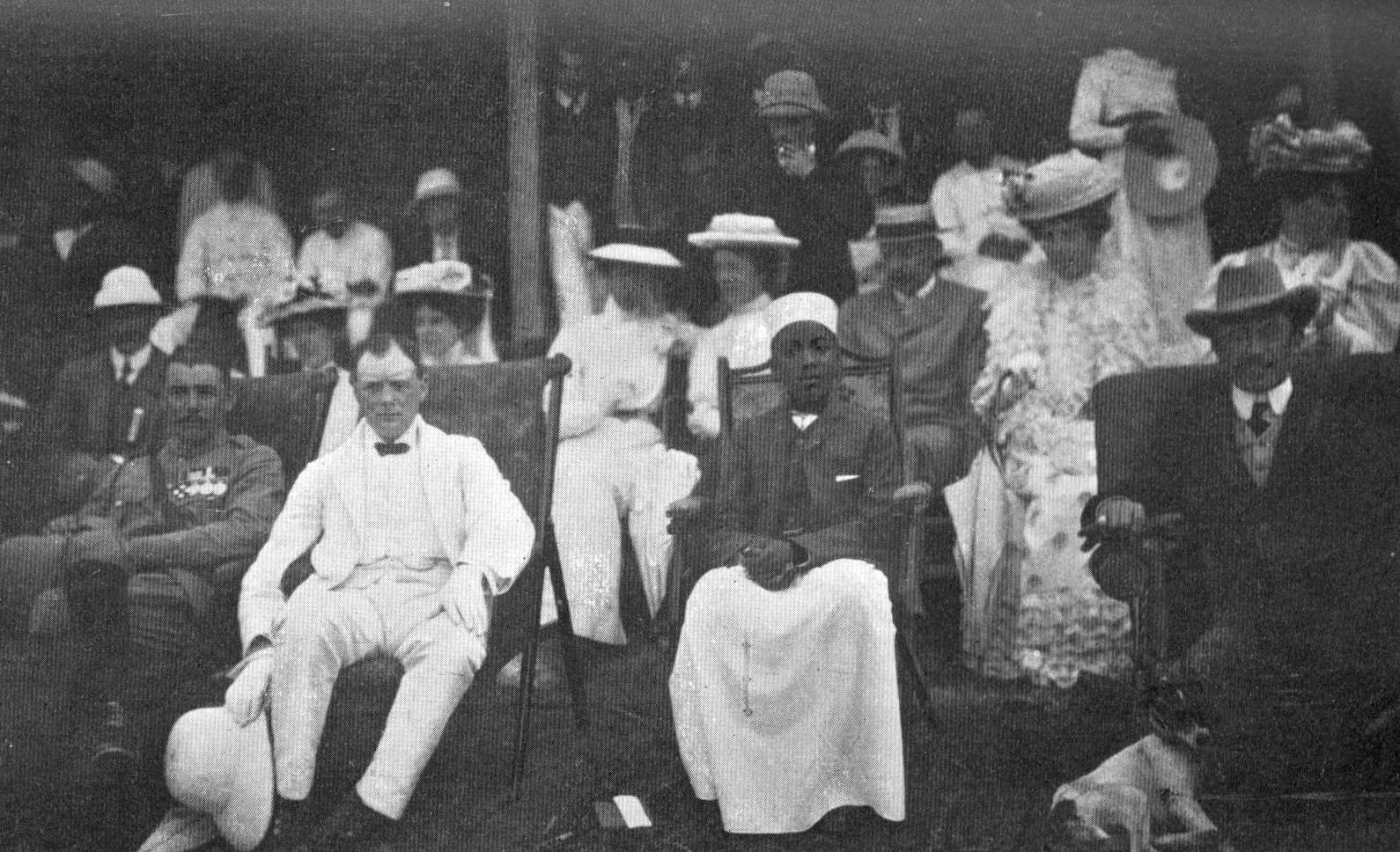

Churchill was born into a world in which virtually all Britons, from the Sovereign to a Covent Garden grocer, believed in their moral superiority. They preached it to their children. All learned that the red portions of the map showed where Britannic civilization had tamed savagery and cured pandemics. Churchill’s assertions, especially as a young man, were often in line with this. And yet he consistently displayed this odd streak of magnanimity and libertarian impulse.

It was Churchill, the aristocratic Victorian, who argued that Dervish enemy in Sudan had a “claim beyond the grave…no less good than that which any of our countrymen could make.” In South Africa, he asserted that Boer racism was intolerable, that the Indian minority deserved the same rights as all British citizens. (This was something Gandhi never forgot, though Churchill did—which Gandhi praised years later, when they were opponents over the India Bill.)

Fair play and magnanimity

After the Great War ended, this same Churchill urged that shiploads of food be sent to a starving Germany as the wartime blockade ended. Other leaders preferred to “squeeze Germany till the pips squeaked.” They did, and the long-term results were not good.

The Jallianwala Bagh or Armritsar massacre of Indians in 1919 found Churchill in full cry against the perpetrators. It was Churchill who in 1920 secured India’s support in the future Hitler war, and assured independent India’s military legacy. Arthur Herman in Gandhi & Churchill writes:

For every disgruntled or discouraged subaltern who joined Japan’s puppet Indian National Army, a dozen KCIOs and VCOs served with distinction on every front in the British war effort…. And the minister of war who created the KCIOs in 1920 had been Winston Churchill…. Churchill never grasped the full magnitude of what he had done, but Gandhi nearly did. Many times over the years he had spoken of brave Indian soldiers who would defend their country and then return home to carry the future burden of freedom.

In the 1920s, it was Churchill who argued that the coal miners should be compensated after the 1926 General Strike. In the 1940s it was Churchill, not FDR, certainly not Stalin, who declared carpet bombing German cities morally reprehensible. Ten years later, he denied South Africa’s demand for Basutoland, Bechuanaland and Swaziland without the consent of their inhabitants.

A singular record

No statesmen of stature exhibited such magnanimity for so long: Not the leaders of the Tory or Labour parties; not the chieftains of wars. Many who heard Churchill’s proposals shook their heads. Some thought him a mental case, a traitor to his class, or a good man gone soft. “I have asserted many times and without being contradicted,” writes historian Larry Arnn, “that Winston Churchill never said or implied that the rights of any person were conditioned upon the color of his or her skin.”

There are countless examples of Churchill’s magnanimity bucking what Andrew Roberts called “The Respectable Tendency.” He recognized and cited the rights of minorities and the oppressed long before the World Wars. He understood that the claim to liberty was not Britain’s alone, and that understanding welled up in his finest hour. Yet similar views had governed his political thought virtually from the start.

Verdict of historians

I often quote what William Manchester wrote. Churchill, he declared,

…always had second and third thoughts, and they usually improved as he went along. It was part of his pattern of response to any political issue that while his early reactions were often emotional, and even unworthy of him, they were usually succeeded by reason and generosity. Given time, he could devise imaginative solutions.

Martin Gilbert wrote about the thousands of documents he examined in writing the Official Biography:

I never felt that he was going to spring an unpleasant surprise on me. I might find that he was adopting views with which I disagreed. But I always knew that there would be nothing to cause me to think: “How shocking, how appalling.”

Yet today some writers profess shock at Churchill’s stray, emotional, unworthy remark. Time and again, the full context of what he said produces an entirely opposite impression.

On the matter of Eugenics (Part 1), to equate Churchill’s record with “the extremities practiced to a tee by the Nazis is”—forgive me—pretty extreme.

One thought on “Winston Churchill, Magnanimity and the “Feeble-Minded,” Part 2”

I recently came across a copy of Piers Brendon’s Winston Churchill: A Brief Life (1984). Would you have perhaps reviewed it, and if so where might I find that file?

Right now I am about half way through the book. To this point it seems to be just what it claims to be, a brief account of WSC’s life, and nicely written. But interesting here is that it reflects your point that in Churchill’s time beliefs in what was right are not necessarily those we hold today.

I believe that with each generation we become more conscious of human rights and take action accordingly. WSC, with his “fair play and magnanimity,” demonstrated that. We still have a long way to go and there have been many terrible falls in the centuries along the way. On the flip side, we are increasingly encountering excesses of zealotry in the name of human rights that actually erode them. But overall I think we are inching forward. Thus 100 years ago, even 60 years ago when I was a young adult in the UK, there was the belief by the British in their “moral superiority,” but that expressed today would be quite rightly condemned. It makes no sense to vilify, by the standards we hold today, the beliefs held in good faith by past generations. No matter how wrong they now appear, they were sincerely thought to be for the betterment and advance of civilization. It is not logical to use today’s standards to judge standards of past ages. Yet today many supposedly educated people apparently cannot grasp that simple truism.

=

Well said, thank-you. I’ve emailed you two reviews of Piers Brendon’s book, which certainly meet Emerson’s dictum never to read anything that is not at least a year old. I published them back in 1984. Dr. Brendon is an old friend, former Keeper of the Churchill Archives, and recently the author of Churchill’s Bestiary, a charming book on WSC and animals, which I reviewed with pleasure. That didn’t prevent Ashley Redburn and me from criticizing parts of his Brief Life, though it has its many good points. He is more diffident about WSC than I am, but honest differences of opinion are all to the good.

You will have to forgive me for not buying into the “only a man of his time” excuse. My maxim in defense of WSC is: surrender nothing, lest you lose everything. If we try to let him off with the excuse that “everybody back then was a racist,” we do him an injustice. Young Winston made himself very unpopular with the Edwardian establishment, defending the likes of blacks and Indians early on, and preaching human rights to the Boers long after everybody else was excusing them. Arguably he could have furthered his career by just “going along.” You might like my pieces on South Africa beginning here. I greatly appreciate your thoughtful comments. —RML

Comments are closed.