Winston Churchill and Polo, Part 2, by Barbara Langworth

“Winston Churchill and Polo” was first published in 1991. It is now updated and amended, thanks to the rich store of material available in The Churchill Documents published by Hillsdale College Press. This article is abridged without footnotes from the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the complete text and footnotes, click here.

============== Continued from Part 1…

Part 2: Dislocations

On 18 December 1898 Winston Churchill wrote to his friend Aylmer Haldane. “I am leaving the army in April. I have come back merely for the Polo Tournaments.” He told his mother he would stay at Government House. He was “playing polo quite well now. Never again shall I be able to do so. Everything will have to go to the war chest.”

Fortune interfered: “Everything smiled until last night—when I fell downstairs and sprained both my ankle and dislocated my right shoulder,” he wrote his brother Jack in February.

In his autobiography three decades later, Churchill wrote that he first dislocated his shoulder on arriving in India in 1896. At the Bombay quayside he had grabbed an iron hand-hold ring when the boat fell with a sudden surge and he wrenched his shoulder. Thereafter, he wrote, he had to play polo with his arm strapped to his side.

* * *

His letters at the time make no mention of this incident. It was his habit to mention injuries—an injured knee in December 1896, for example. In the first version of this article (1991), I suggested that Churchill’s first dislocation likely occurred after falling at Government House in 1898, rather than the much more romantic quayside episode in 1896. Upon reflection and expert advice, I believe Churchill’s version is correct. After describing the Bombay accident he writes: “Since then, at irregular intervals my shoulder has dislocated on the most unexpected pretexts; sleeping with my arm under the pillow, taking a book from the library shelves, slipping on a staircase, swimming, etc.” (Emphasis mine.) This makes it clear that Bombay was the initial incident, although his staircase fall two years later certainly aggravated his condition.

Even with his arm immobilized, Churchill managed to play well. His team beat the 5th Dragoon Guards 16-2, and the 9th Lancers 2-1, in the first round on 23 February. “Few of that merry throng were destined to see old age,” Churchill ruminated sadly. “Our own team was never to play again. A year later Albert Savory was killed in the Transvaal, Barnes was grievously wounded in Natal, and I became a sedentary politician increasingly crippled by my wretched shoulder.”

Playing on

Despite his departure from the home of polo, Churchill continued to play. An appointment book for 1901, his first year in Parliament, showed ten dates in May and June. Listed for Saturday July 6th was “House of Commons versus Guards.” The games on Monday-Wednesday August 5th-7th were marked “Windsor.”

In 1902 Churchill wrote a long letter to Secretary of State for War St. John Brodrick. He argued against a proposed prohibition of inter-regimental polo tournaments. He attributed the increasing cost of ponies to the English gentry’s participation in the game. Polo, he wrote, contributed to building a soldier’s character and skill. Two years later (after opposing Brodrick over the latter’s army estimates), Churchill left the Tories for the Liberal Party. As a consequence, he felt obliged to alter his club membership. It is often said that Churchill was unaware of the political animus he engendered. But in May 1905 he remarked to Liberal MP Alexander Murray (later Baron Murray of Elibank):

I foolishly allowed myself to be proposed for Hurlingham as a polo playing member; & was of course at once black-balled. This is almost without precedent in the history of the Club—as polo players are always welcomed. I do not think you and your Liberal friends realize the intense political bitterness which is felt against me on the other side.

Polo in later life

Pushing fifty, polo was still very much Churchill’s sport. In the summer of 1921, for example, he and his wife were looking for a family summer cottage. Clementine rented one of the houses at Rugby School, near Ashby St Ledger. “The plan was that Winston would stay with them all,” her biographer wrote, “and be diverted by polo with his Guest cousins.” This the same year Clementine cautioned Winston against speculating in stocks…. “Politics are absolutely engrossing to you…and now you have painting for leisure and polo for excitement and danger.”

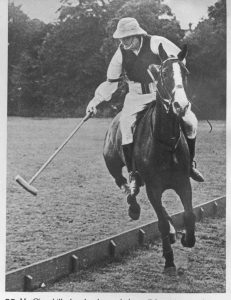

At Chartwell, which he bought in 1922, Churchill would sometimes embark on a well-meant but briefly kept economy programs. In 1926 he suggested that Chartwell be rented and that all livestock—except the two polo ponies—be sold. The ponies were still sacred! Many photographs exist of the mature Churchill at play, always with his right arm strapped to his side. A group picture taken on 18 June 1925 shows WSC with fellow players Capt. G.R.G. Shaw, Captain Euan Wallace and Captain the Hon. Freddie Guest, after Churchill’s Commons team defeated the House of Lords. Winston and Clementine are seen at Hurlingham the same year, to watch the British Army play polo against an American team.

Last chukka

Winston’s last game had the longest gestation of all. Plans for it began in the autumn of 1926, when Admiral Sir Roger Keyes invited Churchill, who was taking a holiday cruise in the Mediterranean, to inspect the fleet. They were old friends, having met during polo around 1904, according to Keyes’s biographer. In those days young Keyes and his friends “would drive down to Wembley and play polo on hired ponies from 8 to 9 am. Often, before they finished, a party of young Members of Parliament would arrive to play from 9 to 10 am. It was at Wembley that [Keyes] first made the acquaintance of Winston Churchill.”

Responding to Keyes’s invitation, Churchill replied on 15 November:

As to Polo, of course I should love to have a game. It is awfully kind of you to offer to mount me. It would have to be a mild one as I have not played all this season. However I will arrange to have a gallop or two beforehand so as to ‘calibrate’ my tailor muscles [sartorius]. Anyhow I will bring a couple of sticks and do my best. If I expire on the ground it will at any rate be a worthy end!

Taken at a gallop, he must have reasoned, and would later write in My Early Life, it would be a very good death to die.

* * *

The enthusiastic Sir Roger replied immediately. “Don’t bother to bring polo sticks—you will find all kinds and lengths here. What is your Hurlingham handicap? We’ll get up a four chucker [sic] match for one day after you’ve had a bit of practice. I expect 4 would be about enough if you haven’t been playing—also where do you like playing?”

On 24 December 1926 Churchill wrote Keyes in Malta. “I shall be with you in plenty of time to play on Saturday afternoon [8 January]. I do not think one day’s practice would do me much good; in fact it would only make one stiff. I hope to do a little hacking in the next few days, if the snow which now overlays us should permit.”

Evidently, Churchill managed his final game without mishap. From Admiralty House, Malta, 10 January 1927 he wrote Clementine: “I got through the polo without shame or distinction & enjoyed it so much.”

At age 52, that was the last recorded occasion when Winston Churchill played polo.

Author’s note

Barbara F. Langworth is a New Hampshire publisher and editor. “Churchill and Polo” was first published in 1991. This updated, amended version is published by kind permission of the author in response to reader requests for more information on Churchill’s favorite team sport. The article incidentally demonstrates the rich store of material available in The Churchill Documents, published by Hillsdale College Press.

Endnotes

Barbara Langworth is a bacteriologist, editor and publisher in New Hampshire. Multi-talented, she runs everything.

One thought on “Winston Churchill and Polo, Part 2, by Barbara Langworth”

Enjoyed your article Barbara about the well known game Winston Churchill played in his early carreer.

Comments are closed.