Winston Churchill and Polo, Part 1, by Barbara Langworth

“Winston Churchill and Polo” was first published in 1991. It is now updated and amended, thanks to the rich store of material available in The Churchill Documents published by Hillsdale College Press. This article is abridged without footnotes from the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the complete text and footnotes, click here.

==============

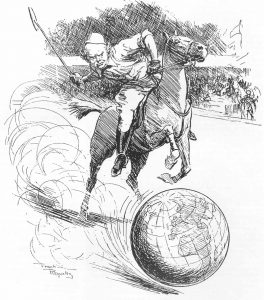

Churchill loved polo, which he called “The Emperor of Games.” A contemporary writer’s description of his polo tactics is remindful of much else in the statesmen’s approach to life and politics:

He rides in the game like heavy cavalry getting into position for the assault. He trots about, keenly watchful, biding his time, a matter of tactics and strategy. Abruptly he sees his chance, and he gathers his pony and charges in, neither deft nor graceful, but full of tearing physical energy—and skillful with it too. He bears down opposition by the weight of his dash, and strikes the ball. Did I say strike? He slashes the ball.

Sandhurst

Churchill first mentions polo in a letter to his father, seeking permission to ride in September 1893. He had just arrived at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. In the entrance exam, his final test score was too low for him to be accepted in the infantry and qualified him only for the Cavalry. This was a disappointment to his father Lord Randolph, who was troubled by the expense: “In the infantry one has to keep a man; in the cavalry a man and a horse as well.” His son recalled later: “Little did he foresee not only one horse, but two official chargers and one or two hunters besides, to say nothing of the string of polo ponies!”

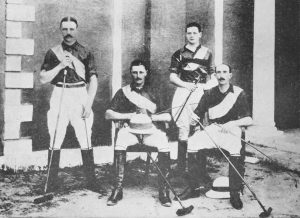

In the spring of 1894, Colonel J.P. Brabazon expressed interest in having Winston join a cavalry regiment. He wrote his mother, Lady Randolph: “How I wish I were going into the 4th [Hussars] instead of those old [60th] Rifles. It would not cost a penny more & the regiment goes to India in 3 years which is just right for me.” Following Lord Randolph’s death in January 1895, Winston duly joined the 4th Hussars. On 12 February 1895 he received his commission as a second lieutenant.

Polo at Aldershot

At Aldershot the same month, Churchill began intensive training as a cavalry officer. As his father had feared, finances were a problem. It was a stretch for their mother to maintain Jack, Winston and herself in the way they would all like. And by now young Winston had discovered polo. In April 1895 he wrote his mother,

Everyone here is beginning to play as the season is just commencing. I have practised on other people’s ponies for 10 days and am improving very fast. If therefore, as I imagine—you have some ready money do lend me a hundred pounds…. I cannot go on without any for more than a few days unless I give up the game, which would be dreadful.

Churchill played regularly during his eighteen months at Aldershot. By May 1896 he was hoping to make the regimental team. “I am making extraordinary progress at Polo,” he wrote his mother, “but I want very much to buy another pony, I wish you would lend me £200 as I could then buy a really first class animal which would always fetch his price.”

It bears mentioning, in those far off days, that £200 had the purchasing power of £20,000 today. It is like your son asking for a loan to buy a car…

For six months he lived in London and played polo at Hurlingham in Essex and Ranelagh. As summer ended the 4th Hussars gave up their cavalry chargers to a returning regiment, and sailed for India.

India

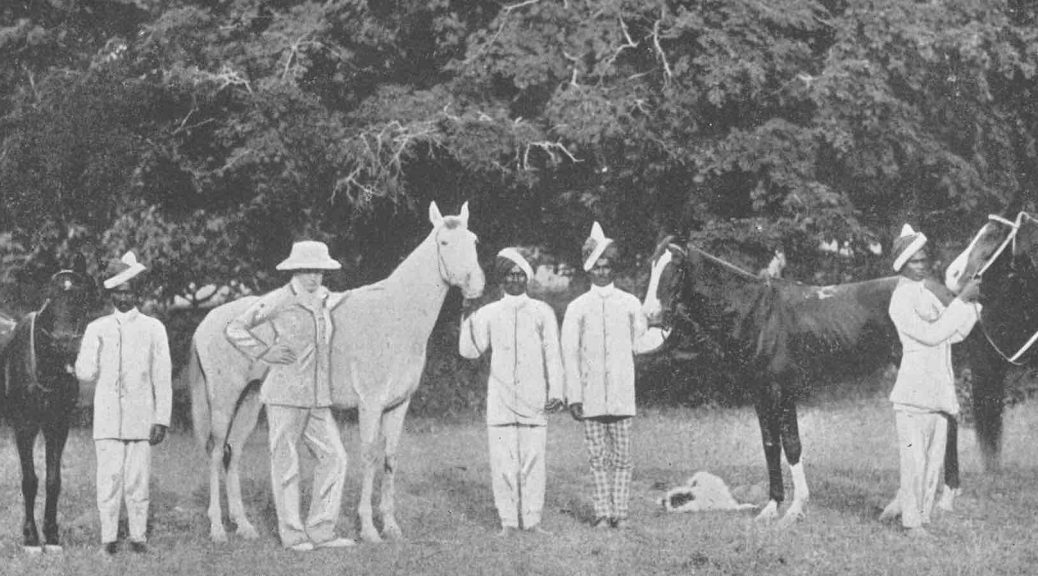

In Bombay a native regiment, the Poona Light Horse, was thought to have the best ponies. In what Churchill called an “audacious and colossal undertaking,” the 4th Hussars bought a complete polo stud of twenty-five horses. This gave them a huge advantage of well-trained ponies immediately upon arrival at their duty station, Bangalore in the south of India.

The Hussars were out to win, and Winston’s letters home were full of the sport. “I get up here at 5 o’clock every morning…ride off to parade at 6. At 8 o’clock breakfast and bath and such papers as there are: 9.15 to 10.45 Stables—and no other engagement till Polo at 4.15.″

A polo game lasts an hour and is divided into periods or chukkas of seven minutes each. Churchill played in every chukka he could get into. His prodigious efforts soon came to the notice of the Aga Khan. “It was at Poona in the late summer of 1896 that our paths first crossed,” the Khan wrote later:

A group of officers of the 4th Hussars, then stationed at Bangalore, called on me…. none was a better judge of a horse, than a young subaltern by the name of Winston Spencer Churchill. He was a little over twenty, eager, irrepressible, and already an enthusiastic, courageous, and promising polo player.

“Give your son horses”

In November 1896 Churchill’s team won a tournament at Hyderabad, a 24-hour, 700-mile train journey. Winston told his mother that the entire population turned out to watch, not infrequently betting thousands of rupees:

This performance is a record: no English regiment ever having won a first-class tournament within a month of their arrival in India. The Indian papers express surprise and admiration. I will send you by the next mail some interesting instantaneous photographs of the match — in which you will remark me—fiercely struggling with turbaned warriors….

Churchill was fond of other horse sports; he participated in steeplechases, point-to-points and pleasure riding. In a letter to Jack in November 1896, he proudly noted that their father’s racing colors, chocolate and pink, would appear on Indian soil for the first time at a pony race meeting. In his 1930 autobiography Churchill would advise parents:

Don’t give your son money. As far as you can afford it give him horses. No one ever came to grief— except honourable grief—through riding horses. No hour of life is lost that is spent in the saddle. Young men have often been ruined through owning horses, or through backing horses, but never through riding them; unless of course they break their necks, which, taken at a gallop, is a very good death to die.

Expanding horizons

During leave in 1897, Churchill traveled in Europe and then went home to England. By September he was back in India, chasing fame and notoriety as a war correspondent with Sir Bindon Blood and the Malakand Field Force. From Nowshera he wrote polo team-mate Reginald Barnes, “Best luck at Poona. It is bloody hot.”

Lt. Churchill returned to Bangalore—“to polo and my friends”—in October 1897. But the success of his writing, and the realization that it could be a serious source of income, had taken the edge off his consumption with polo. “I am off to Hyderabad on Sat for a polo tournament,” he wrote his mother. “It is a nuisance having to go when I am so busy.” He referred to the writing of his first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force. Hoping for more action in the Sudan, where General Kitchener had been appointed to reconquer that territory on behalf of Britain and Egypt, was later attached to the 21st Lancers. This adventure provided material for his second book, The River War.

* * *

Before he left India he got “rid of every polo pony I possess…. I hope to get rid of them all soon. They eat.” Churchill would not return to India again, and would soon leave the army. The Malakand Field Force “earned me in a few months two years’ pay as a subaltern.” He was about to publish his novel Savrola and had offers to write biographies of his father and his ancestor the First Duke of Marlborough. Above all, however, Churchill hungered for a seat in Parliament.

Concluded in Part 2.

_____

Barbara Langworth is a bacteriologist, editor and publisher in New Hampshire. Multi-talented, she runs everything.