Churchill, Canada and the Perspective of History (Part 1)

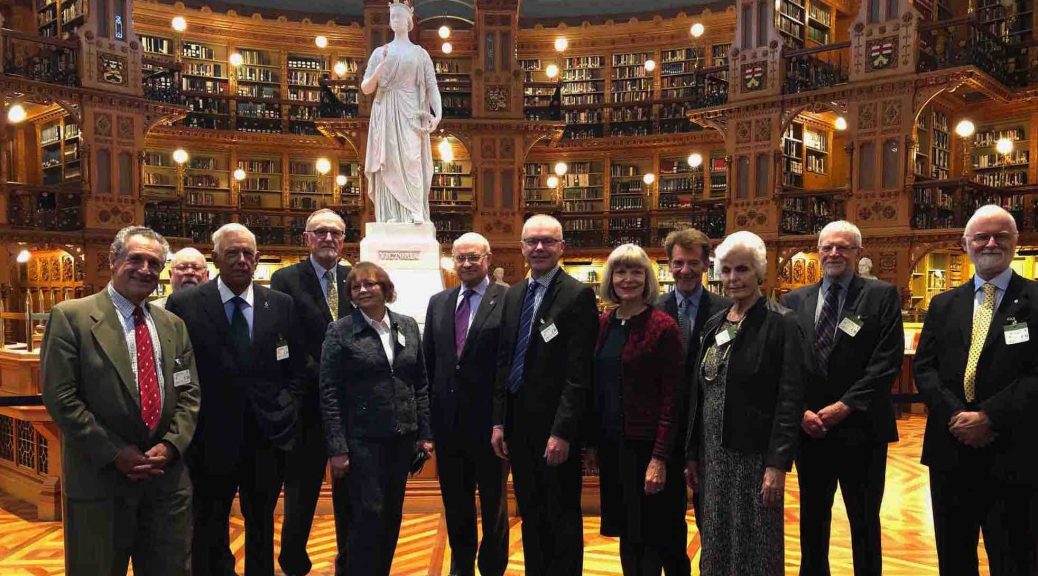

Address to the Sir Winston Churchill Society of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, on Churchill’s 144th birthday, 30 November 2018 (Part 1). We were kindly hosted at Earnscliffe by the British High Commissioner, Susan le Jeune d’Allegeershecque.

Churchill and Canada, 144 Years On

I thank Ron Cohen. And return his compliments. I thank him for his scholarship—especially his great Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill, which is one of the eight or ten standard works on Winston Churchill. And for his prowess as bag man, helping me empty the bookshops of Hay-on-Wye, which he has just described to you.

In 1954, Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent arrived in London, exhausted from a world tour. A frequent traveler, Sir Winston offered him advice: “Never stand when you can sit. Never sit when you can lie down. Never miss an opportunity to visit a washroom.” It falls on me to stand. But since I promised Ron not to take more than 3 1/2 hours, I’m sure I can make it.

Sir Winston lies at Bladon in English earth, “which in his finest hour he held inviolate.” He would enjoy the controversy he stirs today, on media he never dreamed of. He would revel in the assaults of his detractors, the ripostes of his defenders. The vision “of middle-aged gentlemen who are my political opponents being in a state of uproar and fury is really quite exhilarating to me,” he said. Yes, and the not so middle-aged, too.

I have five quick points to make. One of them is Churchill’s overriding message—I differ in this from some of my colleagues. Another is, Churchill’s encounters with Canada. They are many, and they are important. I’ll then describe what Canada meant to him. And I’ll say what the world thinks of him right now. Finally we’ll look at where he stands in the perspective of history: what is it about him that is most worth bringing to the attention of thoughtful people.

What is Churchill’s overriding message?

At this hour on New Year’s Eve 1941, the day after he spoke here, describing Britain as a chicken with an unwringable neck, Churchill was on a train hurtling past Niagara Falls. He was heading back to Washington, to finish telling the Americans what the war was like. You probably know what he said when a colleague urged him to approach the U.S. with caution and deference. “Oh! That is the way we talked to her while we were wooing her. Now that she is in the harem, we talk to her quite differently!”

The war had gone global, and Mr. Churchill was on top of his game. As the sweep second hand of “The Turnip,” his gold Breguet pocket watch, counted down the final moments of 1941, he called staff and reporters to the dining car. There, raising his glass, he made this toast: “Here’s to 1942. Here’s to a year of toil—a year of struggle and peril, and a long step forward toward victory. May we all come through safe and with honour.” That was a tough year. But came through we did.

I think this was his overriding message then. I think it is still his message today. No, there is no Third Reich, no Imperial Japan. But there are stateless enemies who seek our ruin. There is economic uncertainty. There are strains between old friends. What a time for Churchill’s strength and optimism. And there he is to encourage us: never despair, we will all come through safe and with honor.

* * *

How often he knew exactly what to say! It’s true he insisted that the people had the “lion heart,” that he had merely provided the roar; that he had always earned his living by his pen and his tongue. What did they expect? They came through that time in part because they were led by a professional writer. And today, 144 years since his birth, his words, statesmanship, optimism and courage still beckon to us. We are right to worry over current events. And to remember Churchill’s unswerving faith that all will come right.

I like what a Churchill speaker, the publisher William Rusher, said to us at a conference in Banff: “I know we have a tendency to be discouraged about how things are going,” Bill said, “although in our time, you know, they haven’t gone all that badly. The Marxist idea lies in ruins. Free market economics, which I wouldn’t have given you a plugged nickel for at the end of World War II, is now so popular that even China calls its policy ‘Market Socialism,’ whatever that is. These are big victories. There is still much that is worrisome. But Churchill, if he were here, would encourage us: Never despair. Never give in.” Good advice. And just look–despite all the kerfuffle, we even have new North American trade deal!

Encounters with Canada

Our theme is the perspective of history, and since we are where we are, let’s start with the perspective of Canada—for much has emerged about Churchill and what he called “the linchpin of the English-speaking world.”

David Dilks’s 2005 book The Great Dominion is a signal legacy. Churchill loved Canada, David wrote. “He never returned to India after 1899, or to South Africa after the Boer War. He never visited Australia, New Zealand, British Southeast Asia, the British Pacific. Half-American though he was, he never considered the Great Dominion an appendix to the United States, nor regarded Canadians as decaffeinated Americans.”

In early 1901 he was lecturing in Manitoba, which astonished him. “At the back of the town,” he wrote his mother, “there is a wheat field 980 miles long and 230 broad…a visit here is most exhilarating.” It was there that he heard Queen Victoria had died. He was struck by the shared sense of loss: “The news reached us at Winnipeg,” he wrote, “and this city far away among the snows, 1400 miles from any town of importance, began to hang its head and hoist half-masted flags.”

* * *

On his next visit in 1929 he contemplated moving here. “Darling, I am greatly attracted to this country,” he wrote his wife. “Immense developments are going forward….I have made up my mind that if Neville Chamberlain is made leader of the Conservative Party or anyone else of that kind, I clear out of politics and see if I cannot make you and the kittens a little more comfortable before I die. Only one goal still attracts me, and if that were barred I should quit the dreary field for pastures new….But the time for decision is not yet.”

Who knows what would have happened? Would he have become a Vancouver timber mogul, an Edmonton oil baron, or got into Parliament? Probably the latter. After all, as he once told the U.S. Congress, if things had been different he might have got there on his own. It’s probably just as well, I think we all agree, that he didn’t emigrate—Neville or no Neville.

What did Canada mean to Churchill?

He visited Canada again on his 1932 lecture tour, four times during the war, twice in the Fifties—nine times in all. Fifty-four years after his first visit he arrived for his last. “I love coming,” he told reporters. “Canada is the master link in Anglo-American unity, apart from all her other glories.” And he added, in French—“I think of Canada as being almost my own country.”

He respected Canada’s contributions to liberty. “We have not journeyed all this way across the centuries, across the oceans, across the mountains, across the prairies,” he told Canadians in 1941, “because we are made of sugar candy.” They didn’t have to be told. Today we see in Canada tolerance, equality, the golden rule. Eighty years ago there was a somewhat limited tolerance for certain persons, and it led to playing a huge part in the wars that made us what we are today.

When World War I ended 100 years ago last month, Canada had suffered 263,000 casualties, eight times the number per capita of the USA. When World War II began, Canada had 10,000 soldiers and ten Bren guns. By the end of the war there were a million men in uniform, and 25,000 enlisted women. 107,000 were killed or wounded, again more per capita than the United States.

* * *

At dinner here at Laurier House after his 1941 speech to Parliament, Prime Minister Mackenzie King said, “Canada plans to make an immediate gift to you of one billion dollars.” Churchill, accustomed to speaking in English terms of “a thousand million,” wasn’t sure he’d heard right. He asked King to repeat himself. “A billion dollars,” Mr. King said. Then he added two billion in cash and interest-free loans. That is $57 billion in today’s money—twice the size of your current defense budget. Churchill was floored.

From the start of the war, Canadian food supplies and convoys kept Britain from starving. Toward the end, Canadian miners supplied ingredients for “Tube Alloys,” the atomic bomb. Deputy Prime Minister Clement Attlee scarcely knew about it. “Mackenzie King knew everything about it, through Minister of Munitions C.D. Howe, who held a seat on the project’s board.

Nor was World War II the end of Canada’s contributions. Canadians fought and died in Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan. A Canadian general directed the NATO effort in Libya. No peacekeeping force in the past fifty years was without Canadians.

David Dilks brought all this out masterfully in his book. “That is what Canada has done,” he said—“in NATO, the UN, the Commonwealth and in peace-keeping operations. My audience contains many distinguished Canadians. I hope they will allow me to say what is felt by countless people in Britain and America, but too seldom expressed: Thank you a thousand times.”

Continued in Part 2…

One thought on “Churchill, Canada and the Perspective of History (Part 1)”

Bravo for your speech in Canada. Sorry I couldn’t be there in person. Instead I spoke to your friends of the New England Churchillians in Boston on Nov. 3oth. A good meeting with extra time to enrich Brattle Bookshop and have more than one bowl of chowdah. All the best to you and Barbara.

Comments are closed.