A Detailed Review of “Churchill by Himself”

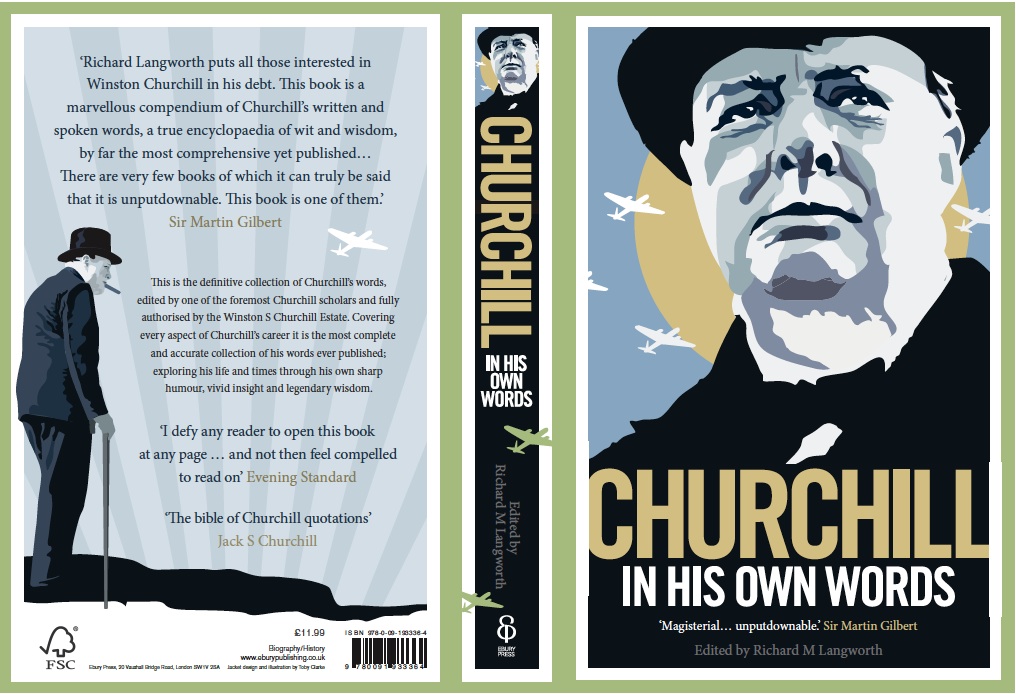

Richard M. Langworth, ed., Churchill by Himself (2008), Churchill in His Own Words (2012), ebook edition by Rosetta Books, 2015.

Heights of Sublimity: A Landmark in Churchill Studies

by Manfred Weidhorn

Dr. Weidhorn was Guterman Professor of English, Yeshiva University, author of four books on Churchill including the seminal Sword and Pen. His review, first published in 2009, is reprinted by kind permission. Readers may also be interested in a shorter review by R. Emmett Tyrrell.

The great man by himself

When one reads a book for the purposes of teaching or scholarship or rebuttal, the usual procedure is to highlight important passages. Richard Langworth has done just that with the vast corpus of Churchill’s writings and speeches. Within the covers of one thick volume, our Happy Reaper has gathered them all. All of Churchill’s witticisms, maxims, and ripostes. And a rich selection of his scintillating prose passages.

The source for each passage is scrupulously given (including the occasional uncertainty). And, at long last, those few famous utterances which Churchill did not make are included. These are in an appendix, entitled “Red Herrings.” No more should there be inquiries as to whether or where Churchill said this or that. Now, as Casey Stengel used to say, “You can look it up.”

Churchill at his best

Here is a distillation of Churchill by Himself: the writer and orator at his very best. We see him in all the various periods of his uniquely long career. He began a callow youth seeking both fame and vocation. He became a fire-breathing young radical, then a “triphibian” military expert. Next he was a Cassandra warning about India (alas!) and Hitler (cheers!). He became the greatest war leader of a democracy in peril (with apologies to Lloyd George and FDR). By himself again, he was the Cold Warrior, meeting “jaw-to-jaw” instead of in war. Then, finally, he became a sage in the era of Mutually Assured Destruction. He was unwilling to surrender hope despite the ambiguities of technological progress which he himself feared.

What other political leader, living through so many phases and tackling so many different issues, possessed so much curiosity in so many areas, so much erudition and such a consistently mesmerizing style? Ah, but what other leader was a professional writer?

Churchill by Himself also reminds us of Churchill’s Falstaffian side: The corpulent man who likes his drink. The man never at a loss for a quip just when others think they have him trapped.

He trended through the decades from a severe criticism of laissez faire capitalism to a severe criticism of socialism. This he brilliantly called “Queuetopia.” By himself, unlike most knee-jerk anti-communists, he understood the complexity of life: “Bolshevism is a great evil, but it has arisen out of great social evils” (147).

The same insight he would also apply to Hitler and Nazism, though not so succinctly. He had a jarring warning for knee-jerk radicals, as well: “Those who talk of revolution ought to be prepared for the guillotine” (394).

“Study history!”

Such observations are based on an understanding of the past (“Study history!”), and reading Churchill by Himself reminds us of some of the fateful junctures of history. It’s not just that in 1931 his famous near fatal taxi accident almost lost us the Second World War. It’s also that, in 1929, at the eerily arithmetical midpoint of his career, he was toying with the idea of retiring from politics and even emigrating to Canada (155).

The letter expressing such velleities suggests that his My Early Life, being written at that time, was a valedictory memoir. Did he think his sadly unfulfilled career might become a mere footnote in history? A “study,” as Robert Rhodes James put it, “in failure”?

But he stayed on, and compelling are the selections from the speeches of the 1930s, on the rearming of Germany and the flaccidity of the Baldwin-Chamberlain response. Juxtaposed with each other in Churchill by Himself, these passages create a chill in the reader, as he temporarily suspends his awareness of the ultimate happy though costly outcome.

Organizing an encyclopedia

With such a wealth of material (twenty million words) on such a wide range of topics, Mr. Langworth faced a major decision about organization. Would he go by alphabet, or chronology, or topic? A tough call. In the end, he arrived at a happy compromise: Broad topics (though in no inevitable pattern). Alphabetically-ordered subdivisions within them; chronology within the latter.

As warranted, Langworth allowed himself variations and exceptions. It is not always a perfect solution—for example, one of Churchill’s greatest sentences, the one about being turned out after five years’ success, is hard to track down. So is the fascinating question of when he first expressed the ambition to become Prime Minister. Or when he spoke of the exhilaration of being shot at without result. The index simply cannot perform all that is asked of it—the index to the new 2025 edition is far more capable. But the result is better than that of all those other schemata that have been tried from time to time.

“Virgil to the reader’s Dante”

Greatly helpful are the cross references among the famous utterances. These are part of the editor’s sage interventions. After every two or three items, Langworth provides brief comments (footnotes, as it were). These clarify, correlate, quote, refer, contextualize, and sometimes take a wider view. When necessary, he glances at recent or current events and tendencies, but in an objective, non-partisan fashion. One therefore cannot tell—and rightly so–whether he is a Left or Right Churchillian. We can tell only that his erudition is immense.

With these judicious notes, Langworth is the Virgil to the reader’s Dante. And that image is not far-fetched, for the journey takes us through vast tracts of Hell and Purgatory. It even proffers (beyond Virgil’s power) glimpses of heaven—or at least of peace and relatively good times.

Churchill’s unique prose

Bringing together the best of Churchilliana reminds the reader that, not only does Churchill’s prose (in any period of his career, unlike the poetry of the gradually maturing Shakespeare) roll as smoothly as the Mississippi River. But, except for some occasional boilerplate about patriotism, duty, and morality—legitimate values necessary in a leader’s rhetorical arsenal but often overdone by lesser politicians—it shows little of the Victorian purple rhetoric that some “modern” (as Churchill might have said with a sneer) literary critics have complained about.

Passage after passage demands to be read aloud for the sheer aural and verbal effects. Churchill’s brilliance was in discursive reasoning and expository prose. In Churchill by Himself it’s there right at the beginning. As in, for example, his prescient and eloquent argument in 1901 that future European wars would be dreadful (504).

His had a unique way of expressing himself, whether in rolling period, in careful or stimulating choice of words. In a surprising twist of thought, he inspired use of concrete detail. Just note one example of the many amusing ways he had of asserting that a political opponent was wrong or untruthful (or that the opponent had only by chance stumbled upon the truth): “An uncontrollable fondness for fiction forbade him to forsake it for a fact” (232). Where in American politics, since that lovable Senator Everett Dirksen in the 1960s—though he was often more windbag than Churchillian–do we have anybody like that? For shame, inarticulate Americans!

Homely simile, apt metaphor

But no less stunning is the eruption of the apt homely simile or metaphor that brings the discussion home to even the dullest mind. To wit, many people have observed that the opposite extremes of Communism and Fascism actually meet. They are a line becoming a circle. But only Churchill comes up with the apt analogy of the North and South Poles, equally cold and barren (384).

Consider other examples: “Every offensive lost its force as it proceeded. It was like throwing a bucket of water over the floor” (23). Or: “China, as the years pass, is being eaten by Japan like an artichoke, leaf by leaf” (157). Warning against the “great folly” of extending the Korean War into China, he said, “It would be like flies invading fly paper” (437).

About his curious fusion of agnosticism and traditionalism: “I am not a pillar of the church but a buttress—I support it from the outside” (465). Or take this paean to democracy: “The alternation of parties in power, like the rotation of crops, has beneficial results” (110). Or his at once poetic, patriotic, and mischievous praise of the American foundational document: “No constitution was written in better English” (127).

“”Drill sergeant of words”

Then there is the matter of his unprecedented and risky injection of humor into speeches addressing the most dire situations: “We are waiting for the long-promised invasion. So are the fishes” (160). On discontinuing the plan to ring church bells to warn that the German army has landed: ”I cannot help feeling that anything like a serious invasion would be bound to leak out” (297).

Hitler, in forgetting about the Russian winter, “must have been very loosely educated….I have never made such a bad mistake as that” (347). Or take the earthy way he has in making the pedestrian military observation that Hitler has lost air power superiority: “Hitler made a contract with the demon of the air, but the contract ran out before the job was done, and the demon has taken on an engagement with the rival firm” (207).

But to cite these examples is to betray hundreds of equally great ones. What a drill sergeant of words he was, and what an outrage it was to let someone like him loose to embarrass and humiliate the rest of us mere mortal users of the language!

A trove of profound observations

Legend has it that when Milton’s Paradise Lost was published, John Dryden, the greatest poet of the next generation, said to fellow poets frequenting a coffee house, “This man cuts us all out, and the ancients too.” In the same way, all collections of the “Wit and Wisdom of Churchill” are now rendered automatically obsolete. Indeed it is hard to think of a “Wit and Wisdom” vade mecum devoted to anyone (other than perhaps Shakespeare)—Pope, Twain, Wilde, Shaw, Proust, Lincoln—that is not diminished by the scope of this book, the volume of memorable utterances, the helpful commentary.

As a treasure trove of profound observations, rolling periods, amusing—often hilarious—one-liners, it threatens the hegemony of Bartlett’s Quotations. Who could have thought that any one man had so many wonderful things to say? He makes the value of the other merchandisers of sagacity seem inflated.

A book for lovers of English

Mr. Langworth’s previous publication was a record of the editions of Churchill’s books. That definitive work was of interest only to that class of harmless eccentrics known as book collectors. Churchill by Himself (nice title, too) is of interest to anyone who loves English—nay loves language itself. It shows how this puny, featherless, two-legged creature called man can use his invention of words to reach heights of sublimity.

Churchill by Himself is not conventional scholarship or criticism. It doesn’t advance a new interpretation, or bring to light obscure documents or connect the dots in revisionist fashion. Instead it puts a larger number of dots at our disposal for us to connect. It is nothing less than a landmark in Churchill studies.

Indeed, thanks to Langworth’s well-intentioned efforts, some academic scoundrel will no doubt spare himself the enjoyable but time-consuming task of reading Churchill’s fifty or so books. Rather, he will use just this one volume in order to write a credible monograph on “Churchill’s political philosophy.” Or “Churchill’s Prose Style.” Or “Churchill and …” any number of topics. (Churchill was certainly right to have his doubts about “progress.”)

Related reading: Churchill by Himself

“All the Quotes Winston Churchill Never Said,” Part 1 of four parts, 2018.

“Churchill Quips: God, Santayana, Musso and Not Getting Scuppered,” 2024.

“Churchill by Himself: Errata and Future Editions,” 2019.

“Robert Rhodes James: ‘A Good House of Commons Man,’” 2023.

R. Emmett Tyrrell, “A Short Review of Churchill by Himself,” 2009.