Churchill and the Rhineland: “Terrible Circumstances”

Excerpted from “Churchill and the Rhineland: ‘They Had Only to Act to Win,” written for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original article with footnotes and images, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, enter your email in the box “Stay in touch with us.” Your email is never revealed and remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Hitler to the Reichstag, 7 March 1936

“We dedicate ourselves to achieving an understanding between the peoples of Europe and particularly an understanding with our Western peoples and neighbors. After three years, I believe that, with the present day, the struggle for German equal rights can be regarded as closed…. We have no territorial claims to make in Europe.” (Following this speech, Hitler dissolved the Reichstag.)

The Rhineland challenge

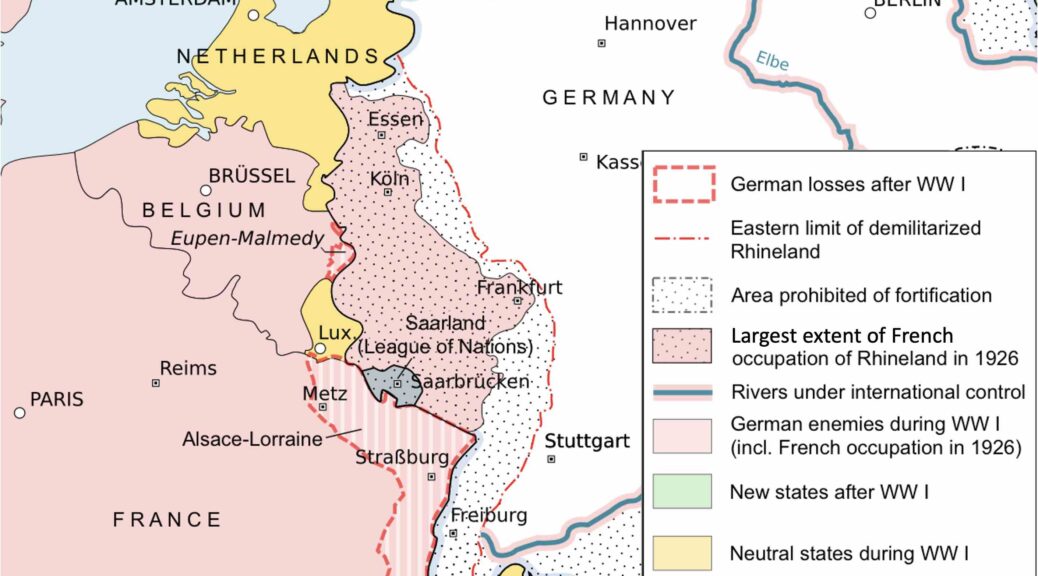

The Rhineland in western Germany is bordered by the River Rhine in the east and France and the Benelux countries in the west. It includes the industrial Ruhr Valley, the famous cities of Aachen, Bonn, Cologne, Düsseldorf, Essen, Koblenz, Mannheim and Weissbaden, and several bridgeheads into Germany proper.

After the end of the First World War, the Rhineland was occupied by the victorious Allies. Though the occupation was set to last through 1935, military forces withdrew in 1930 as a good-will gesture to the Weimar Republic. The Allies retained the right to reoccupy the Rhineland should Germany violate the Treaty of Versailles.

In March 1936, a few thousand German troops marched into the Rhineland while the populace waved swastika flags. The soldiers had orders to “turn back and not to resist” if challenged by the all-dominant French Army. Hitler later said that the forty-eight hours following his action were the tensest of his life.

Churchill’s defenders correctly cite the Rhineland as confirming his warnings about Hitler. But what Churchill actually proposed to do about it is not as clear.

“Confronted by terrible circumstances”

In January 1936, Churchill predicted that a Rhineland incursion would raise “a very grave European issue…. The League of Nations Union folk, who have done their best to get us disarmed, may find themselves confronted by terrible circumstances.”

Hitler’s future foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, recorded how Hitler conceived of slipping the occupation past the Western allies. Summoning Ribbentrop in January, Hitler said: “[I]t occurred to me last night how we can occupy the Rhineland without any friction. We return to the League!” Germany had left the League of Nations in 1933.

Ribbentrop said he too (of course) had this very idea. He suggested they strike while the French and British were on one of their weekend holidays. Hitler acted on Saturday March 7th. France, he said had abrogated the Rhineland agreements by a military alliance with Russia.

True to plan, Hitler added a sweetener, proposing “a real pacification of Europe between states that are equal in rights.” Germany would return to the League of Nations, provided her colonies, stripped at Versailles, were returned.

Would France march?

The question turned on France. Would she reassert control of the Rhineland? Or just dither and do nothing? Anthony Eden, Britain’s foreign secretary, was sanguine: Great Britain would stand by France, and he offered military staff conversations.

Unfortunately for staff conversations, the French military was led by General Maurice Gamelin, a “nondescript fonctionnaire.” The French government may have yearned for a way to stop Hitler. Gamelin and his military colleagues were more worried about stopping him from invading France proper.

British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin believed France was unwilling to act—with or without Britain. Churchill was unsure, given the resolve of French Foreign Minister Pierre Flandin. Four days after Hitler’s action Flandin visited London. Churchill recalled:

He told me he proposed to demand from the British Government simultaneous mobilisation of the land, sea, and air forces of both countries, and that he had received assurances of support from all the nations of the “Little Entente” [Czechoslovakia, Rumania and Yugoslavia] and from other States. He read out an impressive list of the replies received. There was no doubt that superior strength still lay with the Allies of the former war. They had only to act to win.

Baldwin’s reluctance

Churchill urged Flandin to press his views with Baldwin, who was unsympathetic. He knew little of foreign affairs, he said, but he did know the British people wanted peace. Flandin modified his plea. Suppose the Anglo-French “invite” Hitler to leave, pending negotiations, which would probably restore the Rhineland to Germany anyway? Even this was too risky for Baldwin. “I have not the right to involve England,” he said. “Britain is not in a state to go to war.” Flandin was deflated, and as Baldwin suspected, the French cabinet was divided.

The pressure in Britain to avoid action was strong. At a dinner of ex-servicemen in Leicester, one of Churchill’s supporters, Leo Amery, gave a fiery speech. Britain’s very existence was threatened, he exclaimed. To the amazement of one observer, the ex-servicemen sided with the Germans. They said in effect: Why shouldn’t they have their own territory back? It’s no concern of ours.

“No fresh perplexities”

Publicly, Churchill was being cautious. “I was careful not to diverge in the slightest degree from my attitude of severe though friendly criticism of Government policy,” he wrote. The friendliness is more evident than the severity. Churchill did urge a “coordinated plan” under the League of Nations to help France challenge the German action. This was denied. Sir Samuel Hoare replied that the necessary participants in such a plan were “totally unprepared from a military point of view.”

Churchill had political reasons for treading lightly. He had been urging creation of a Ministry of Defense or Supply, which he hoped to be named to head. Baldwin duly announced a “Minister for the Coordination of Defense,” which was something less entirely. Worse, the job went to Solicitor General Sir Thomas Inskip, who knew nothing of the subject.

Inskip’s appointment disappointed Churchill, who, hoping to be called to office, had carefully avoided public criticism of the government. Baldwin, Churchill reminisced, “thought, no doubt, that he had dealt me a politically fatal stroke, and I felt he might well be right.”

Churchill as peacemaker

But Churchill still had an audience. He now began a series of fortnightly articles on foreign affairs for the Evening Standard. In the first, “Britain, Germany and Locarno,” he renewed his call for League of Nations intercession on the Rhineland. He insisted that there was a peaceful way to resolve the problem:

The Germans claim that the Treaty of Locarno has been ruptured by the Franco-Soviet pact. That is their case and it is one that should be argued before the World Court at The Hague. The French have expressed themselves willing to submit this point to arbitration and to abide by the result. Germany should be asked to act in the same spirit and to agree. If the German case is good and the World Court pronounces that the Treaty of Locarno has been vitiated by the Franco-Soviet pact, then clearly the German action, although utterly wrong in method, can not be seriously challenged by the League of Nations.

This is not Churchill the defiant critic of appeasement, but Churchill the statesman. At this point he was urging prudence and adjudication. He did warn that if the League failed in its duty, it might cause events to “slide remorselessly downhill towards the pit in which Western civilization might be fatally engulfed.”

He continued to urge strength and resolution: “I desire to see the collective forces of the world invested with overwhelming power. If you are going to depend on a slight margin, one way or the other, you will have war.”

Collective Security

Churchill’s next article returned to his theme of unified action. This was no task for France and Britain alone, he declared. It was a task for all: “There may still be time. Let the States and people who lie in fear of Germany carry their alarms to the League of Nations at Geneva.” In the absence of French military action he was falling back on Collective Security.

Aside from political considerations, Churchill was attempting to see things from the view of Britain’s closest ally. The French were “afraid of the Germans,” he wrote to The Times; France had joined the sanctions against Italy over Mussolini’s 1935 invasion of Abyssinia, and the resulting estrangement had given Hitler his Rhineland opportunity:

In fact Mr. Baldwin’s Government, from the very highest motives, endorsed by the country at the General Election, has, without helping Abyssinia at all, got France into grievous trouble which has to be compensated by the precise engagement of our armed forces. Surely in the light of these facts, undisputed as I deem them to be, we might at least judge the French, with whom our fortunes appear to be so decisively linked, with a reasonable understanding….

Did Churchill waver?

Winston Churchill favored a collective response to the Rhineland, recognizing its implications. One event followed the other, as the hardline Member of Parliament Robert Boothby recorded later:

The military occupation of the Rhineland separated France from her allies in Eastern Europe. The occupation of Austria isolated Czechoslovakia. The betrayal of Czechoslovakia by the West isolated Poland. The defeat of Poland isolated France. The defeat of France isolated Britain. If Britain had been defeated, the United States would have been given true and total isolation for the first time.

Churchill certainly would have backed French reoccupation of the Rhineland. But evidence suggests that he knew the League was toothless. Churchill’s theme did not dramatically change in 1936; it merely evolved. As early as 1933 he had declared: “Whatever way we turn there is risk. But the least risk and the greatest help will be found in re-creating the Concert of Europe.”

That was not to be. The failure of a concerted response over the Rhineland was to be repeated. Each time western statesmen hoped the latest Hitler inroad would be his last.

Prudence and statesmanship

It is the belief of many thoughtful historians that Churchill said and did nothing about the Rhineland, even in the weeks after he had been denied office. His actions are more complex than that. He did give mixed signals, but he also proposed solutions. When France refused unilateral action, he favored collective action. His public declarations were hardly a clarion call. But we must bear in mind also that he was not in office.

Churchill never admired Hitler, except in the narrow sense of Hitler’s political skills. There is no doubt that he spoke well of Mussolini, up to 1940. Was this because he admired Fascism, or because he hoped to influence the Italian dictator? Until the mid-1930s, Italo-German relations were precarious.

The Rhineland marked Churchill’s final disillusionment over the League of Nations. It impelled his efforts to secure Collective Security through “a coalition of the willing” (to use a more recent and perhaps uncomfortable phrase). The problem was that the willing were few—and demonstrably unwilling to cooperate.

Author’s note

This essay appeared in longer form in my book, Churchill and the Avoidable War: Could World War II Have Been Prevented? (2015). It was prompted years before by Robert Rhodes James’s argument that Churchill said and did nothing to stop Hitler over the Rhineland. I argued otherwise, and he kindly agreed to hear me out. Alas my piece appeared too late for his lifetime, and cost me his almost certain learned response. I miss my friend. RML

Related articles

“Great Contemporaries: The Three Lives of Churchill’s Hitler Essays,” 2024.

“Robert Rhodes James: ‘A Good House of Commons Man,” 2023.

2 thoughts on “Churchill and the Rhineland: “Terrible Circumstances””

It is useful to highlight the Belgian situation at that time, a small country being a buffer between France and Germany. I fully agree to the summary as written by M. Daniel Wybo. Leopold III, King of the Brlgians, did not have any other choice. In the end Belgium was overrun owing to the failure by France and Britain to take proper measures in due time. History could have been different.

–

Mr. van Leemput is National Chairman, Royal Veterans League of King Leopold III.

Some Belgian background: In 1936, Belgium realized that neither the French nor British would do anything about Hitler’s reoccupation of the Rhineland, and France had refused to extend the Maginot line along her border with Belgium. For one of few times in history, the Belgian people were unanimous that their territory should never again be used as a battlefield. Thus Belgium asked to be absolved of 1925 Locarno Treaty obligations and entered into a policy of armed neutrality. The British and French Governments recognized that Belgium was making the most effective contribution towards the security of the surrounding States and doing her utmost to fulfill her function in a part of Europe often exposed to the ravages of war. On 24 April 1937 the British and French governments acknowledged Belgium’s position. Armed neutrality might have reduced the risk, but did not prevent, German aggression. Only the Great Powers could have done that. But Belgium’s policy cemented national unity and strengthened the common will to resist an onslaught of unparalleled violence, the moral torture of a new occupation, and the specter of famine. These were the fundamental safeguards that Belgium needed to have when her very existence was threatened by the storm. I encourage readers to read Richard Langworth’s “Feeding the Crocodile: Was Leopold Guilty?”

–

Mr. Wybo is a spokesman for The Royal League of Veterans of HM King Leopold III.

Comments are closed.