Thoughts on National Churchill Day 2017: TheQuestion.com

Q: TheQuestion tries to provide our readers with the most reliable knowledge from experts in various fields. As we celebrate National Churchill Day, April 9th, we would appreciate your thoughts on three questions. These are currently posted without responses on our website: Was Winston Churchill really that good an artist? What made him a great leader? What was his greatest achievement?

TheQuestion: Churchill as Artist

Please take a virtual tour of Hillsdale College’s recent exhibition of Churchill paintings and artifacts. Here your readers can decide for themselves. The consensus among experts, however, is that Churchill was a gifted amateur. He had genuine talent, but he also had good tutors: Sir John and Lady Lavery, Paul Maze, Walter Sickert. Several professionals—Picasso was one—said that if painting had been his profession, he would have done very well. (Picasso rarely shared his politics, and is reputed to have wished that happened…)

Churchill himself never pretended to be more than an amateur, referring to his 600 oils as “my daubs.” Until very late he resisted exhibiting, and was sensitive to his works being patronized because of his fame. In 1944, General Eisenhower’s chauffeur, an amateur painter, asked if he might show one of his oils to the Prime Minister. “Very good,” Churchill said, “but you, unlike myself, will be judged on talent alone”

TheQuestion: Leadership

To answer TheQuestion’s second query would require many words. Whole books have been written on the subject, notably Churchill on Leadership by Steven Hayward. Churchill’s Trial, by Dr. Larry Arnn, College, considers how Churchill resolved the nature and needs of the citizenry with constitutional democracy and ordered liberty.

In my opinion two qualities of his leadership stand out: his ability to pursue the paramount goal to the exclusion of all rivals, however worthy; and his ability to communicate that goal to a baffled or frightened world. In May and June 1940, he was the only possible choice for premier, because for almost a decade he had warned of Nazi Germany as the primary threat. “I thought I knew a good deal about it all,” he wrote in his memoirs, “and was sure I should not fail.” A year later, when Hitler invaded Russia, he pledged immediate aid to the Soviet Union, which he had long excoriated: “If Hitler invaded Hell, I would at least make a favourable reference to the Devil in the House of Commons.”

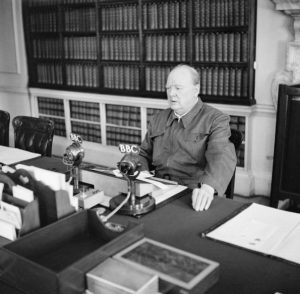

As a communicator he was unique in his time, and perhaps any time. I remember a Belgian lady at a Churchill conference, gripping Lady Soames’s arm to tell her what her father’s wartime speeches had meant to Belgians gathered around surreptitious radios, listening to crackling broadcasts over the forbidden BBC. Ronald Golding, a former RAF pilot who was briefly Churchill’s detective after the war, said: “After one of those speeches, we wanted the Germans to come.”

TheQuestion: Achievement

Churchill himself said “nothing surpasses 1940,” and we must look there for his greatest accomplishment—there, and not the glorious victory years later. Churchill didn’t win the Second World War. Winning took the combined resources of the Empire/Commonwealth, Russia and America. His biggest achievement was not losing it.

And it was, as the old Duke of Wellington said of Waterloo, “a damn close-run thing.” By June 1940, many thought the wisest course was coming to terms with Germany. Churchill resisted, and won them over. “If this long island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.” His colleagues rose and cheered, thumping him on the back. All possibility of making peace with Germany vanished. Promotion for the upcoming film “Darkest Hour” says the movie will for the first time disclose why Churchill fought on. The reasons have been plain since 1940.

A 19th Century Man…

The journalist Charles Krauthammer contemplated events had Churchill not been there,. Hitler, he said, “would have achieved what no other tyrant, not even Napoleon, had ever achieved: mastery of Europe. Civilization would have descended into a darkness the likes of which it had never known.” And Krauthammer eloquently describes the singularity of Churchill’s achievement:

The great movements that underlie history—the development of science, industry, culture, social and political structures—are undeniably powerful, almost determinant. Yet every once in a while, a single person arises without whom everything would be different….Churchill was, of course, not sufficient in bringing victory, but he was uniquely necessary—he then immediately rose to warn prophetically against Nazism’s sister barbarism, Soviet communism.

Churchill is now disparaged for not sharing our multicultural sensibilities. His disrespect for the suffrage movement, his disdain for Gandhi, his resistance to decolonization are undeniable. But that kind of criticism is akin to dethroning Lincoln as the greatest of 19th century Americans because he shared many of his era’s appalling prejudices. In essence, the rap on Churchill is that he was a 19th century man parachuted into the 20th. But is that not precisely to the point? It took a 19th century man—traditional in habit, rational in thought, conservative in temper—to save the 20th century from itself.

…in a Thoroughly Modern Century

The story of the 20th century is a story of revolution wrought by thoroughly modern men: Hitler, Stalin, Mao and above all Lenin, who invented totalitarianism out of Marx’s cryptic and inchoate communism. And it is the story of the modern intellectual, from Ezra Pound to Jean-Paul Sartre, seduced by these modern men of politics and, grotesquely, serving them.

The uniqueness of the 20th century lies not in its science but in its politics. The 20th century was no more scientifically gifted than the 19th, with its Gauss, Darwin, Pasteur, Maxwell and Mendel—all plowing, by the way, less-broken scientific ground than the 20th. No. The originality of the 20th surely lay in its politics. It invented the police state and the command economy, mass mobilization and mass propaganda, mechanized murder and routinized terror—a breathtaking catalog of political creativity. And the 20th is a single story because history saw fit to lodge the entire episode in a single century.

Totalitarianism turned out to be a cul-de-sac. It came and went. It has a beginning and an end, 1917 and 1991, a run of 75 years. That is our story. And who is the hero of that story? Who slew the dragon? Yes, it was the ordinary man, the taxpayer, the grunt who fought and won the wars. It was America and its allies. And it was the great leaders: Roosevelt, de Gaulle, Adenauer, Truman, John Paul II, Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan. But above all, victory required one man without whom the fight would have been lost at the beginning. It required Winston Churchill.