End of Glory: “Into the Storm” with Brendan Gleeson and Janet McTeer (2009)

Into the Storm, a television drama broadcast by the BBC and HBO. Produced by Ridley Scott, directed by Thaddeus O’Sullivan. Brendan Gleeson as Winston Churchill and Janet McTeer as Clementine Churchill. Screenplay by Hugh Whitemore.

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

“To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his gods…”

—“Horatius,” stanza XXVII in Lays of Ancient Rome, by Thomas Babbington Macaulay. Recited at the beginning and at the end of “Into the Storm.”

Here is a TV docudrama packing exceptional honesty. At an age when most men retire (or in his time die), Churchill gets command of his nation when no one else wants it. It is Britain’s greatest crisis in history. They fight alone, save for their kith and kin. And they win—only to see the old man dismissed in the moment of victory.

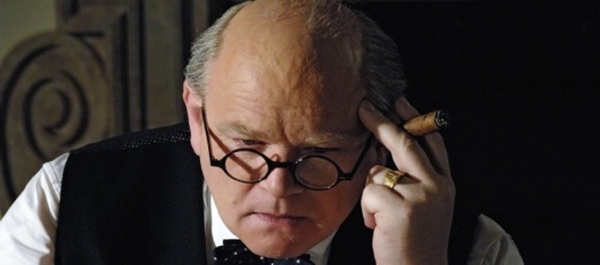

Gleeson at his Churchilllian best

The opening scene is Hendaye, France, July 1945, where Churchill, his wife and daughter Mary spend a week’s break. It is between polling-day in the British General Election and the start of the Potsdam Conference. Anxious for election returns, Churchill relives the past five years in a series of flashbacks. This is the film’s one jarring element. The back-and-forth occurs without obvious transition. You have to remind yourself whether you are in the past or present. It is the only fault worth noting. The story is massive, the action real, the history honest, the dialogue convincing. The scenes are artful, the acting superb.

Brendan Gleeson, who in life speaks with a heavy Irish brogue, is the best Churchill since Robert Hardy. He falls into none of the usual traps. Most Churchill impersonators overdo the accent or the famous lisp. They repeat the V-sign, toilet scenes and siren suits. These are caricatures painted by Lord Moran or Alanbrooke. Gleeson’s work was praised by WSC’s daughter Lady Soames, the sternest of critics.

Good scriptwriting

Hugh Whitemore was sensitive scriptwriter of Scott’s preceding film, “The Gathering Storm.” Again he helps by not loading the dialogue with soaring rhetoric. “Papa spoke in private,” his daughter says, “much as he did in public.” And here is the private Churchill, with doubts about winning, fears of the future, and faults of his own—for he was as human as anyone, freely admitted it, and often apologized for it, especially to his wife.

Several quotes, though real enough, are taken out of time or context. But Whitemore blends them flawlessly into the story, and the student of Churchill’s words doesn’t mind. Several scenes—the famous “naked encounter” with Roosevelt is one—didn’t happen that way, but are so seamlessly integrated and well acted as to make them believable and acceptable. Churchill’s habits—like the mandatory siesta which enabled him to work into the wee hours—are deftly conveyed in a line of dialogue. There is no bending of history for the sake of drama. Only the advanced pedant can object to the film’s artistic license.

Janet McTeer is no Vanessa Redgrave, the archetypal Clementine in “The Gathering Storm.” She doesn’t even look like Clementine, falling short of the character described by her daughter Mary’s biography. Though she gives WSC good advice, she seems more of a neurotic scold than a pillar of strength. It doesn’t matter because Gleeson, “throws himself into the character and completely owns him,” as Daniel Carlson writes, “from the nonstop cigars to the famous cadence of his speeches. Gleeson is believably tough but doesn’t make Churchill a warmonger or bully; if anything, he’s burdened by the thought of the boys he has sent to die.”

Pros and cons

Carlson has his finger on the outstanding quality of this film: its sensitivity to Churchill’s true persona. Despite many opportunities for ignorant political posturing—the leveling of German cities, for example—Scott and Whitemore always have Churchill saying what he truly believed—culled in this case from My Early Life (1930): “War, which used to be cruel and magnificent, has now become cruel and squalid.”

Into the Storm packs less depth than “The Gathering Storm”—like the persecution of Ralph Wigram for sending WSC secret reports on German rearmament, and the bravery of his wife Ava during threats against their family. But too much is going on for sidebars. This is World War II, remember: the French debacle, Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain, the Blitz, Pearl Harbor, Singapore, the fraught meetings with Roosevelt (Len Cariou) and Stalin (Alexy Patrenko), the all-or-nothing assault on Normandy. Leadership is the plot, sub-plot and sidebar.

Better a sequel?

Some Churchillians have asked why Ridley Scott couldn’t have stopped at Pearl Harbor, and done a third film later; why there couldn’t be multiple parts; why it wasn’t a Churchill version of Lord of the Rings. Indeed, I criticized The Gathering Storm for skipping over Neville Chamberlain and Munich. But the best editor I ever worked for said: “A bore is someone who tells everything.” And we are not filmmakers. We have no idea what constraints the producers labored under. We do know that Ridley Scott had ninety minutes. And what he does to portray the real Winston Churchill is a work of genius.

My enduring impression of “Into the Storm” is of an old man, realizing after the most heroic chapter in his country’s history that history itself has passed him by, the Britain he loved vanished before his eyes. “The palmy days of Queen Victoria and a settled world order,” as Churchill put it in 1947, are gone forever. The war is won, the country lost in a Socialist dream. Hardly, alas, unfamiliar: a signal message in 2009.

Modern reflections

A lot of us who grew up in Churchill’s time feel the way Churchill does at the end of this film, as he reads a sympathetic post-election note from his old friend Jack Seely: “I feel our world slipping away.” Churchill thinks back: “I met him in South Africa, riding across the veldt. He was Col. Seely then. I saw him at the head of a column of British cavalry, riding twenty yards in front, on a black horse. I thought of him as the very symbol of Imperial power.”

Watching this film, I had the odd sensation that it was well Britain chose World War II for what John Charmley called “The End of Glory.” British power and faith, focused one last time by a leader steeped in history and language, held the fort “till those who hitherto had been half blind were half ready.” Better to go out in a flash of light than face the long decline that seems now to attend another superpower. “The proud American will go down into his slavery without a fight,” Pravda (astonishingly) declared, “beating his chest and proclaiming to the world how free he really is.” That will take years. For Britain the End of Glory came in months.

“Yes, I’ve worked very hard and achieved a great deal,” Churchill reflected at the end of his long life, “only to achieve nothing in the end.” A life that rose to the heights of fame, the honors of the world showered upon him—for what? “I feel,” he said, “like an aeroplane at the end of its flight, in the dusk, with the petrol running out, in search of a safe landing.”

Not only he.

2 thoughts on “End of Glory: “Into the Storm” with Brendan Gleeson and Janet McTeer (2009)”

I fully agree about that the story is massive, the action real, the history honest, the dialogue convincing, the scenes artful, the acting superb, including Ms.McTeer´s performance. Yes she is no Vanessa Redgrave, but they both are unique actors in their own way. As a Uruguayan fan of British actors and the UK tradition of great theatre, thanks for reminding us of the sacrifice of Churchill’s generation, and the values they fight for.

After World War One, Churchill lamented using Thomas Moore’s words, “I feel like one / Who treads alone / Some banquet-hall deserted, / Whose lights are fled, / Whose garlands dead / And all but he departed!” How much more poignant were those sentiments running through Churchill’s mind after the close of World War Two? Alas, those of us who are steeped in history, especially Churchill’s prophetic observations, must feel today a similar sadness. The values we hold to be true concerning statesmanship, democracy, capitalism, and faith are largely regarded today by the mass of men as an anachronism. Perhaps as we consider what we (America and mankind) have lost, then we can appreciate in part Churchill’s inner turmoil.

Comments are closed.