Wiegrefe: “The Compleat Wrks of Wnstn Chrchl (Abridged)”

The Compleat Wrks (Abridged) by Klaus Wiegrefe

Some things on the web live a long time. “How Winston Churchill Stopped the Nazis” by Klaus Wiegrefe was published ten years ago, but we still get queries about it. This review is therefore republished for your amusement or forgiveness.

This nine-part article is oddly remindful of “The Compleat Wrks of Wilm Shkspr (Abridged).” In that work, three actors critique all of Shakespeare’s works in a couple of hours.

There’s nothing particularly novel or new in Der Spiegel‘s series. Attempts to cast Churchill as demoniac have been going on long before 2021—as bad as today’s stuff is. Wiegrefe does admit that Churchill “Saved Europe.” But one would do better reading about World War II on Wikipedia—or, if you have time, one of the good specialty studies, like Geoffrey Best’s Churchill and War—or, if you really want to know what Churchill thought, his own abridged war memoirs.

“Putzi” and Hitler’s dinner date

The early partss dwell on sagas of Churchill and Hitler starting in 1932. The story then skips ahead to the bombing of Germany. (Wiegrefe says this killed mostly civilians, and Churchill was “strangely ambivalent” about it.) There follows the postwar division of Europe. Much is oversimplified and fails to consider the contemporary reality of fighting for survival—which, after all, is what Churchill and Co. were doing. You make a lot of mistakes doing that.

Part 1 recounts the timeworn story of the stillborn Hitler-Churchill meeting. Hitler’s pro-British foreign press chief, Ernst “Putzi” Hanfstaengl, attempted to arrange this in Munich in 1932. The account (based on Hanfstaengl’s 1957 memoirs) is reasonably accurate. But Wiegrefe concludes that Churchill felt “regret” that the meeting did not take place.

Not so. What Churchill wrote was: “Thus Hitler lost his only chance of meeting me. Later on, when he was all-powerful, I was to receive several invitations from him. But by that time a lot had happened, and I excused myself.” (Gathering Storm, 66). This hardly sounds like regret.

(Putzi himself had regrets. He barely escaped with his life later on, when Goebbels & Co. decided he was a deplorable. Safe in America, he advised Roosevelt about Nazi psychology.)

Functioning prone?

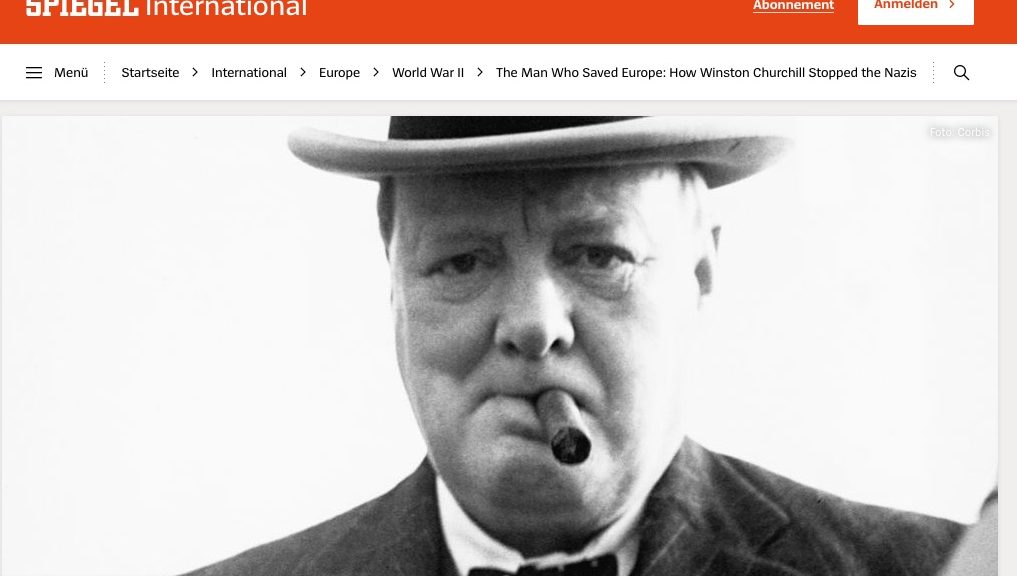

In World War II, Wiegrefe continues, Britain’s premier “conducted a significant portion of government affairs from a horizontal position. Dressed in his red dressing gown, he would lie on his four-poster bed, chewing a cigar and sipping ice-cold soda water, and dictate memos…often titled ‘Action This Day.’”

Of course he dictated correspondence (sitting up) in bed of a morning. It helped him squeeze a day and a half out of every day. He did not conduct the war from his mattress. It’s trivial, but “Action This Day” was a label not a title. He pinned it to notes on which he wanted fast responses. Churchill never drank iced soda water. What he drank was a kind of “scotch-flavored mouthwash.” I thought everybody knew this by the turn of the last century.

Herr Wiegrefe seems confused over the likelihood of a 1940 German invasion of Britain. First he says it was never planned, then that Hitler was ready to launch it if the Royal Air Force “could be put out of commission first.” Next: “The Germans felt they stood a better chance of succeeding in May 1941….” (When they were about to invade the Soviet Union?) The imminence of invasion seemed real enough when the Battle of Britain hung by a thread.

Gas, bombs and razzmatazz

Some authors will never get over the idea that Churchill contemplated using “poison gas,” whether tear gas (Iraq, 1922) or the real stuff. Why, he “even toyed with the idea of dropping poison gas on German cities, but his generals objected.” Any source for that? (We know he was willing to use it in battle—if the enemy used it first. To their credit, they didn’t.)

Understandably, Germans felt the horror of the air bombardment of Germany more than anyone else. Wiegrefe claims that 600,000 died. A scholarly study claims 410,000. Either way, it was tragic. We are told that Churchill admitted that the bombings were “mere acts of terror and wanton destruction.” But this is too brief a condensation of Churchill’s views. Dresden, he wrote to his Chiefs of Staff Committee, “remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing. I am of the opinion that military objectives must henceforward be more strictly studied in our own interests rather than that of the enemy…rather than on mere acts of terror and wanton destruction, however impressive” (Martin Gilbert, Road to Victory, 1257).

Whose ethnic cleansing?

Oversimplification is rampant in Part 9, “Churchill’s Role in the Expulsion of Germans from Easter[n] Europe.” Wiegrefe accuses him of “ethnic cleansing” in moving Poland west at the expense of German Silesia, to accommodate Stalin’s westerly ambitions. The shift of territory required giving resident Germans “a brief amount of time to gather the bare necessities and leave.”

Like the Jews of Germany, perhaps? Leaving to one side how much personal responsibility Churchill bore for the maltreatment of deportees—which often appalled him, whoever was maltreated—one’s heart doesn’t exactly bleed.

A searcher for the truth should contemplate Churchill’s 1942 comment: “The Germans have received back again that measure of fire and steel which they have so often meted out to others.” And then his visit to Berlin in 1945: “My hate had died with their surrender and I was much moved by their demonstrations, and also by their haggard looks and threadbare clothes.” These two sentiments are not too common among politicians.

Sniffing at the trivial

There is no attempt throughout these articles to consider the reality and complexities of fighting a resolute and formidable enemy. Let alone with an ally, the Soviet Union, that might flip or flop various ways depending on its interests. Or play off the Anglo-Americans against each other—which Stalin freely did.

Eighty years on, we have the luxury to sniff at Churchill’s representing the fate of Silesian Germans with matchsticks. Or suggesting “spheres of influence” in Eastern Europe (which saved Greece). War is hell, as General Sherman said. And Churchill’s daughter Mary often remarked, “nobody knew at the time who would win.”

At the end of the war, “the only decision remaining for the Allies was to determine what to do with Hitler and the Germans once they were defeated.” (No worries about the role of the United Nations, decolonization, Stalin, nuclear technology, or European recovery?) “Churchill vacillated between extremes, between a Carthaginian peace and chivalrous generosity. In the end, Stalin’s and Roosevelt’s ideas prevailed.”

“Perhaps he was simply tipsy”

We search for examples of the Carthaginian peace toward which Churchill vacillated. Did he not walk out at Teheran, when Stalin proposed mass executions? And reject the Morgenthau Plan of reducing Germany to an agrarian state, stripped of industry? Did he not endorse the postwar Berlin Airlift? Certainly he urged rapprochement between France and Germany. Was he not the champion of Adenauer, and as good a friend abroad as postwar Germany ever had?

“Before the Holocaust,” Herr Wiegrefe writes, “Churchill toyed with the idea of banishing Hitler and other top Nazis to an isolated island, just as Napoleon had once been banished to Elba. Or perhaps he was simply tipsy when he voiced this idea.”

Perhaps the author was simply tipsy when he wrote these articles. What we have here is a rough capsule history of the war, along with several clangers and exaggerations. But in the main this account is, as Churchill once said about Britain and the Axis ganging up against Russia: “Too easy to be good.”