Musical Interludes: Churchill and the Violin, 1886, 1928

Q: Did Winston Churchill play the violin?

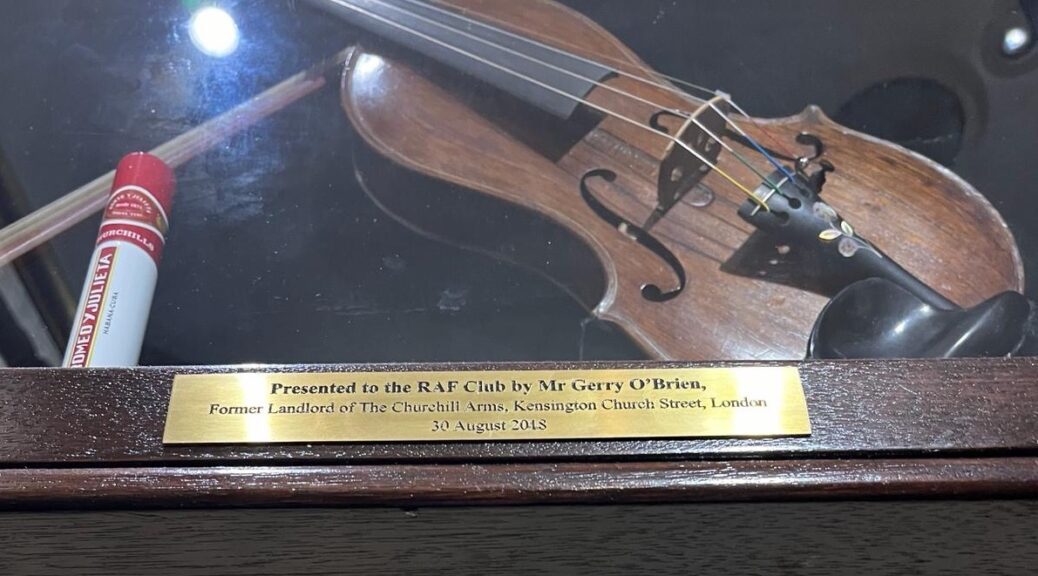

Do you know if Sir Winston ever owned a violin? What might be the history of this one, in the Churchill Bar in the RAF Club, 128 Piccadilly? It was presented by Gerry O’Brien upon his retirement as owner of the Churchill Arms pub in Kensington. —Paul Rafferty (N.B.: Mr. Rafferty, an art historian, is author of the authoritative study, Winston Churchill Painting on the French Riviera, 2020.)

A: Twice, circa 1886 and late 1920s

Churchill dabbled twice with the violin: as a schoolboy in the 1880s, and as a Cabinet minister in the late 1920s. This charming keepsake relates to his later interest in the instrument.

An article in the Summer 2024 RAF Club magazine notes that this violin was made from J.J. Fox cigar boxes once owned by Churchill. It was once played by Sir Yehudi Menuhin, and was recently heard again in the RAF Salon Orchestra. Mr. O’Brien purchased it at auction in 2016.

Churchill wrote: “One may imagine that a man who blew the trumpet for his living would be glad to play the violin for his amusement.” [1] He certainly blew his own trumpet for his living, bust he also hankered to play the violin.

“The Violincello or if not the Violin…”

Pushing twelve in 1886, young Winston wrote his mother from boarding school: “I want to know if I may learn the Violincello or if not the Violin instead of the Piano. I feel that I shall never get on much in learning to play the piano, but I want to learn the Violincello very much indeed and as several of the other boys are going to learn…. [2]

Barry Singer in Churchill Style suggests his interest was shortlived, because classical music really wasn’t his thing:

He also studied piano, but begged to be allowed to learn the cello or the violin instead. Classical music interested him very little-despite his mother’s own taste for the operas of Wagner…and the piano ducts of Beethoven and Schumann…. Winston favored music hall tunes, for which he had a prodigious memory, or patter songs from the Savoy Operas of Gilbert and Sullivan that he loved to sing in his soft treble voice. [3]

“Winston was always keen to try his hand at something new,” adds Celia Sandys, but he did not inherit his mother’s gift as a musician. [4] Indeed, his early wish to play violin or ’cello was not repeated in his youthful correspondence.

Violinist Chancellor

Violinist Chancellor

Without the work of an early biographer, Robert Lewis Taylor, we would not know of Churchill’s second encounter with the violin. This occurred when he as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1924-29.

A popular historian, Taylor unearthed odd facts and interviewed obscure people who knew the younger Churchill. Unfortunately, his Informal Study of Greatness is without endnotes, but we can quote it easily enough:

It is not widely known that Churchill, in a period of political crisis, once bought a cheap violin and essayed to prepare himself for the concert stage. The fancy passed. Unlike bricklaying, the musical art was tougher than it looked. About all he got out of it was a witticism from Philip Snowden, a government opponent, who said, “I understand that Winston has taken up a new pastime—fiddling, and very appropriate, too.” [5]

That quip is a charming reminder of Churchill’s omnipresent collegiality. Snowden was the socialist Chancellor who succeeded Churchill after Labour’s triumph in the 1929 election. They agreed on virtually nothing, and exchanged pointed barbs across the floor of the house.

But there was mutual respect, even admiration, and after Snowden died in 1937, Churchill put him into his book Great Contemporaries: “The British democracy should be proud of Philip Snowden. He was a man capable of maintaining the structure of Society while at the same time championing the interests of the masses.” [6]

Without more definite provenance we may only guess, but it would seem logical that Churchill presented this violin after “the fancy passed” in the late 1920s or early 1930s. There is no evidence that he actually owned one as a boy, but Taylor confirms that he did acquire one later.

Violinist in spirit

Writing in 1953, the philosopher Cyril Joad suggested that Churchill was at least a figurative violinist: One may be a philosopher in two senses, Joad wrote. The first, obviously is when you make it your business. But there is also a “looser sense,” where someone “who has touched life at many points may comment at large upon men and things, distilling in aphorisms and epigrams, in maxims and exhortations, the ripe fruits of his mellow experience.” [7] That perfectly describes Winston Churchill. Joad continued:

Plato and Aristotle were philosophers in both senses; Descartes and Kant and Locke in the first; while King Solomon, Samuel Johnson, Goethe, Lincoln and Winston Churchill belong predominantly in the second.

Philosophers of this second group must not only formulate their philosophy but practise and apply it in public. But then for all of us, philosophers or not, life is like that; it is as if one were giving a public performance on the violin when one has to learn to play the instrument as one goes along. [8]

Endnotes

[1] Winston S. Churchill (hereinafter WSC), “Hobbies,” in Thoughts and Adventures (London: Thornton Butterworth, 1932, rep. Leo Cooper 1992), 220.

[2] WSC to Lady Randolph Churchill, Brighton, 13 July 1886, in Randolph S. Churchill, ed., The Churchill Documents, vol. 1 (Hillsdale, Mich.: Hillsdale College Press, 2006), 123.

[3] Barry Singer, Churchill Style: The Art of Being Winston Churchill (New York: Abrams, 2012), 23.

[4] Celia Sandys, From Winston with Love and Kisses (London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1994), 122.

[5] Robert Lewis Taylor, Winston Churchill: An Informal Study of Greatness (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1952), retitled The Amazing Mr. Churchill (1962), 407. This book was recently republished and is available from Amazon.

[6] WSC, “Philip Snowden,” in Richard M. Langworth, ed., Churchill by Himself (New York: Rosetta Books, 2015), 374.

[7] Cyril E.M. Joad, “Churchill the Philosopher,” in Charles Eade, ed., Churchill by His Contemporaries (London: Hutchinson, 1953), 326.

[8] Ibid., 327.

Related reading

“The Music Winston Churchill Loved (with Audio Links),” 2018.

“Irving Berlin, Isaiah Berlin: Churchill’s Mistaken Identity,” 2023.

“Vanishing National Anthems: Do We Still Know the Words?” 2024.