Churchill Quotations: “The Artist, the Invalid, and the Sybarite”

Q: Sybarite, invalid, artist…

In his first letter as a war correspondent attached to the Malakand Field Force (3 September 1897) Winston Churchill wrote of Rawalpindi: “When I recall the dusty roads, the burnt-up grass, the intense heat, and the deserted barracks, I am unable to recommend it as a resting-place for either the sybarite, the invalid or the artist.”

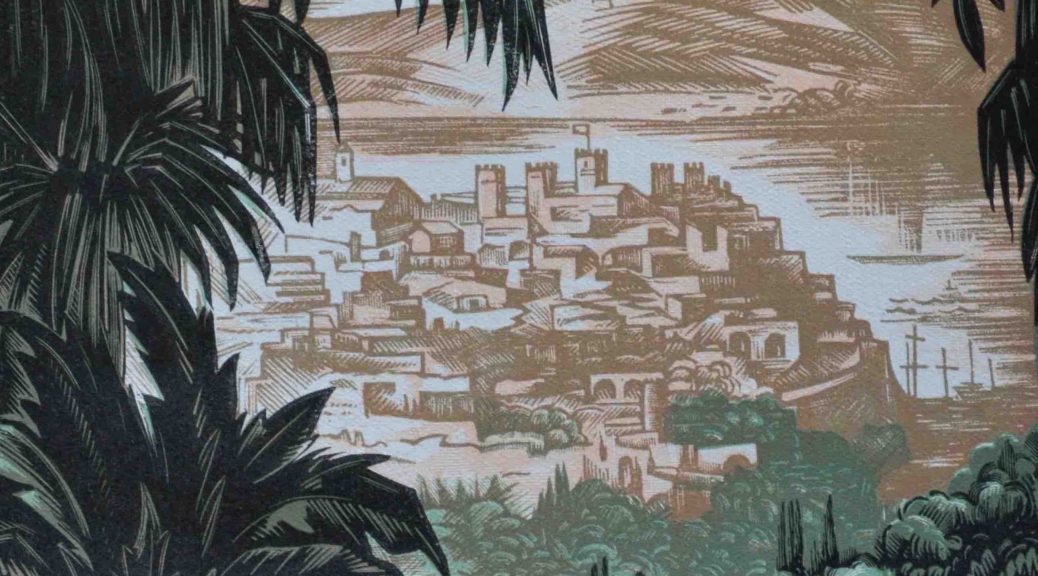

Three years later, his only novel, Savrola, opened with a description of the fictional Mediterranean Republic of Laurania: “It was the first rain after the summer heats, and it marked the beginning of that delightful autumn climate which has made the Lauranian capital the home of the artist, the invalid, and the sybarite.”

Do you not think that there is, in a psychological sense, something significant about this repetition? I believe “the sybarite, the invalid, and the artist” were always together in his mind. He would not recommend Rawalpindi as even “a resting-place” to any of them. Yet he ventured to establish the capital of Laurania as a home for all three! (Churchill started writing Savrola upon his return to Bangalore from the north.)

How can these three ubiquitous but unrelated figures be accounted for? Could it be that the invalid was his late father Lord Randolph (who had visited India in the mid 1880s), the sybarite his spendthrift mother (from whom he received a steady supply of expensive books); and the artist himself (then of only words, but later also of colours)? If not, then how might one explain the repetition of so singular a choice of nouns?

It is also interesting, and perhaps pertinent, that the expression in question does not, so far as I am aware, appear in the book The Story of the Malakand Field Force (1898). —Bilal Haider Junejo, London

A: An ear for the congenial phrase

This interesting question first went to Andrew Roberts, who replied: “I think answer is more straightforward than your Freudian take. Churchill constantly self-plagiarised, especially in speeches but you have found an example in his writing too. He thought poetically, and if a phrase such as ‘the sybarite, the invalid or the artist’ seemed to work, he thought nothing of re-using it, and why not?” Dr. Roberts forwarded his reply to me, and I agreed (we almost always do!), adding some observations…

Churchill had an ear for the congenial phrase, and a photographic memory that reprised favored lines years apart. Andrew recalled how the Hillsdale Churchill Project tracked the famous phrase “Let us go forward together,” to 17 appearances between 1910 and 1959. There was also “the magic of averages,” which Churchill deployed when referring to social insurance between the 1910s and 1940s. Then there was Bourke Cockran‘s “the earth if a generous mother.” Young Winston first heard that around the turn of the last century, and was repeating it (with credit to Cockran) into the late 1950s.

If Laurania, why not Morocco?

As for the lack of a sybarite and other figures in the Malakand, that book was not a collection of war despatches, although based in part on them. The phrase was clearly lingering in his mind when he wrote Savrola.

But there are no other occurrences of “the sybarite, the invalid or the artist” (and other combinations) in Churchill’s published canon. Evidently it didn’t “stick” as well as “forward together” or “magic of averages.” If it had, he might have applied it to Morocco or the South of France–where he was all three of those things from time to time. Next to Chartwell, he loved them most. He found both to be perfect for convalescing, painting, or enjoying the luxuries of life. (Of course, he knew where to stay!)

Sybarite but not Lotus-eater

While searching for “sybarite” I found several examples of Churchill himself being so described. Princess Bibesco wrote in Churchill: Master of Courage (1957) that he was born and remained a sybarite. Paul Alkon wrote of Savrola in Winston Churchill’s Imagination (2006):

There is a touch of sybaritic imagination at work when Churchill describes the “great reception-room” of the Presidential Palace almost as though issuing directives for an architect commissioned to design young Winston’s own ideal prime minister’s residence. (146)

But WSC cannot be judged a sybarite in isolation from his other traits. Roy Jenkins, whose Churchill (2001) approaches but doesn’t equal Andrew Roberts’ Walking with Destiny, writes:

His sybaritic tastes only attained full satisfaction when they were superimposed on a period of high and testing achievement. He had not enjoyed his convalescence [from a stroke in 1953], and commented on it in an engaging way. “I have not had much fun,” was his dismissal of July. He may have been a sybarite, but he was as far as it is possible to imagine from being a lotus-eater. He did not welcome old age, and he knew that the best way to stave off the effects was to postpone the time when power had gone for the last time. Thereafter it would be downhill all the way. (868)

I cannot disagree with that.