Secretarial Masterpiece: A Churchillian Reader by Cita Stelzer

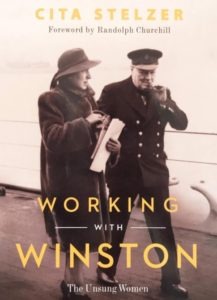

Cita Stelzer, Working with Winston: The Unsung Women Behind Britain’s Greatest Statesman. New York, Pegasus Books, 2019, 400 pages, $28.95, Amazon $19.35, Kindle $14.99. Excerpted from a review for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the full text, click here.

Grace Hamblin came to Chartwell in 1932 and served as secretary to both Churchills. After Sir Winston’s death she became Chartwell’s first National Trust administrator. Through all those years she never “wrote.” Nor, with one exception, did his other office secretaries. The exception was Elizabeth Layton Nel. Her lovely book, originally Mr. Churchill’s Secretary, was written with Churchill’s approval, and in the kindest terms.

For the record

Hamblin and many others knew their experiences would be valuable to history. Thus they cooperated by making recordings with Churchill Archives Centre. That is where Cita Stelzer first went in search of her untold story. But Mrs. Stelzer did not stop there: her nine-page bibliography testifies to the countless sources she consulted.

Nothing like this has been attempted before. There are many compilations by and about those who knew and worked with Churchill. But all those involved “the good and the great.” Stelzer instead offers the unsung heroines (and one hero) who spent their prime in Churchill’s “private office.”

The author is mindful of the vast cultural gulf between their time and ours. Today, she notes, “women of equal talent and willingness to work would have grander titles.” Today they’d be called—at the very least—”executive assistants.”

The grand triumvirate

The first three chapters cover the most stellar and important of Churchill’s secretaries: Violet Pearman, Grace Hamblin and Kathleen Hill. Between them they piled up forty years of experience.

Pearman, the imperturbable “Mrs. P.,” served from 1929 to 1938. She took ill, but continued to serve part-time from her home until she died of a stroke in 1941. Grace Hamblin “broke in” at Chartwell under Mrs. P. “She worked like a Trojan,” Grace remembered.

Hamblin herself has been often mentioned in Churchill lore. She was involved in every aspect of his affairs. There was no difference in priority, she said, either. Stopping at the Post Office for the latest page proofs was no more important than fetching the a shipment of maggots for Churchill’s goldfish. She often remembered how she would rush off to the village after summons by the postmaster. “Is that the secretary? Yer maggots are ‘ere, Miss!”

Kathleen Hill arrived in July 1937 to assist Grace and Mrs. P. as the European scene darkened and Churchill’s political and literary work built. “Hill would work for Mrs. Churchill in the mornings, rest during the afternoon, and then work for Churchill at nights, sometimes until 2 or 3 a.m.,” Cita Stelzer writes.

“Klop”

Hill wasn’t on the job a day when Churchill commanded: “Fetch me Klop.” She remembered seeing a lengthy study of the Stuarts by the German historian Onno Klopp. Proudly she staggered down two flights of stairs with fourteen volumes of Der Fall des Hauses Stuart und die Succession des Houses Hannover. “God Almighty!” Churchill roared.

“Klop” was a “Churchillism”—a word invented “for reasons of onomatopoeia.” It was a metal hole-punch that allowed a “Treasury tag” (a length of yarn with metal “Ts” at its ends) to secure pages together. He detested staples and paper clips, because, he said, “they are very dangerous as they pick up and hold together wrong papers.” Realizing his explosion had hurt Mrs. Hill’s feelings, Stelzer writes, “he complimented her on her handwriting.”

Their value was beyond their station

There are nine further chapters on these remarkable characters. The above gives the flavor of them all: the warm humanity, the humor and affection, between the staff and the boss.

“Secretaries” or “shorthand typists” is what they were called in their day. Sometimes with a new one Churchill would forget her name, and refer to “Miss” or “the secretary” or “young woman.” Not one of them ever felt demeaned by this. They certainly were distressed when Churchill, deep in thought, flew into a rage over some minor mistake. But their loyalty and love never diminished. None ever tried to profit by careless revelations, or by leaking privileged gossip. They respected Churchill, as he, in the end, did them.

Reading Cita Stelzer’s pages bring to mind what Churchill said when the local gypsy, “Mrs. Donkey Jack,” was hospitalized. Churchill paid for her care and sent a gardener to feed her dogs. One of them, small and fierce, stood watch over her caravan in the Chartwell Wood. “He allows Arnold to bring food at a respectable distance, and consents to eat it,” Churchill wrote his wife. “But otherwise he remains like the seraph Abdiel in Paradise Lost. ‘Among innumerable false, unmoved, Unshaken, unseduced, unterrified; His loyalty he kept, his love, his zeal.’ A fine moral lesson to the baser breed of man!”