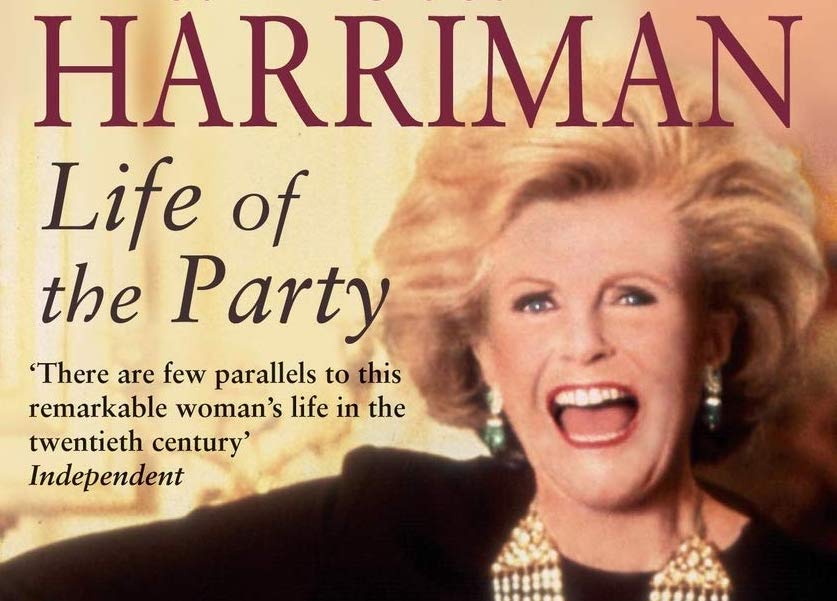

Pamela Beryl Digby Churchill Hayward Harriman 1920-1997

In a 1956 edition of his 1899 novel Savrola, Churchill quoted Emerson: “Never read a book that is not at least a year old.” I can give reassurance on this point, since Christopher Ogden’s Life of the Party: The Biography of Pamela Harriman, was published in 2006. I was reminded of Ogden (and update my review) by a new Pamela book I won’t be reading. The first one from that author was enough

• First published as “Great Contemporaries, Pamela Harriman,” Hillsdale College Churchill Project. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale/Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, and enter your email in the box “Stay in touch with us.” We never spam you and your identity remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Pamela: she got there on her own

In 1941 at the U.S. Congress, Winston Churchill disarmed whatever remaining critics he still had by declaring: “Had my father been American and my mother English, instead of the other way round, I might have got here on my own.” Pamela Harriman (1920-1997) was all-English, yet rose to high American office on her own. She served as U.S. ambassador to Paris from 1993 until her death. Small-minded people, and there are plenty, belittle her lack of education, her glittery friendships with the great. All that is easy to mock, but beside the point.

Her colleague Richard Holbrooke rated her quite differently: “She spoke the language, she knew the country, she knew its leadership. She was one of the best.” President Jacques Chirac compared her to the two most notable American ambassadors, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. He awarded her a Commander of the Legion d’Honneur‘s Order of Arts and Letters, France’s highest cultural award. Pretty good for a girl from the sticks who left home early, determined to succeed.

Pamela Beryl Digby was born in Farnborough, Hampshire, daughter of the 11th Baron Digby. Her mother Constance was the daughter of 2nd Baron Aberdare. Her childhood home was her first Churchill connection. Minterne Magna in 1642 was the residence of John Churchill, father of the first Sir Winston.

A skilled horsewoman, Pamela competed at show-jumping including Olympia, where every fence was above her pony’s shoulders. In 1937 she was at a boarding school in Munich when she met Adolf Hitler—a dubious achievement her future father-in-law missed. Introduced by his admirer Unity Mitford, Pam never fell for whatever spell the Führer cast over Mitford.

“You are not still a Catholic?”

Pamela Digby’s first marriage, at age nineteen in 1939, was to Randolph Churchill, a decision taken on the fly. Randolph was off to war and, thinking he might be killed, anxious to produce an heir. Reportedly he had proposed to eight other women before Pamela.

Friends and family, she recalled, warned her that the mercurial Randolph was not a good long-term risk: Conservative Chief Whip David Margesson, “took me for a long walk in the country and tried to dissuade me.” She replied: “If he is not killed and we do not get on together, I shall obtain a divorce.” In 1946, she was as good as her word.

Thomas Maier, author of The Churchills and the Kennedys, says the only Churchill concerned about the match was Winston. “Your family, the Digby family, were Catholic, but I imagine you are not still a Catholic?” he asked her. WSC had no religious prejudice, but as a politician always had to contemplate potential criticism.

Pamela assured him the Digbys had long been Church of England, and faithful Conservatives. “Yes, you had your heads chopped off in the Gunpowder Plot,” Churchill smiled. “That is right,” she answered—Sir Everard Digby.” (Mr. Maier notes that Sir Everard, a Catholic convert, was actually hung, drawn and quartered.)

“How great a man…”

Winston Churchill welcomed Pamela into the family. Becoming Prime Minister, he invited her to Downing Street. Pregnant with her son Winston, she recalled sleeping in a bunk bed in the bomb shelter, “one Churchill above me, another inside.” Pamela loved and admired the PM, and later did amusing imitations of him in her own deep voice.

Once during dinner amidst the Blitz, Churchill gazed around the table. “If the Germans come,” he told them, “you can always take one with you.” Pamela, all of twenty, was shocked at this. “But Papa,” she protested, “what would I fight with?”

WSC peered at her with a benignant smile: “You, my dear, may use a carving knife.” Her son Winston said she recited that vignette often, captivated by her father-in-law’s indomitable spirit. He added: “It was through her that it first dawned on me how great a man my grandfather was.”

Randolph to Averell

As friends had warned her, marriage with Randolph was not destined to be smooth. Neither were celibate in each other’s absence, and her affair with Roosevelt’s envoy, Averell Harriman, was an open secret. Winston nor Clementine never spoke of it.

Contrary to what you may hear from other sources, she fell for Averell the moment she laid eyes on him, one Blitz night at the Dorchester. There was no plot by Winston to use her. Inevitably, when he learned of it, Randolph Churchill exploded. Years later it still strained relations between father and son. But Randolph was hardly guiltless of indiscretions.

After her divorce, with little in her pocket except determination, Pamela and her young son Winston moved to Paris. She enjoyed a lavish life and romances. In 1960 she married Broadway producer Leland Hayward (renowned for South Pacific and The Sound of Music.) The marriage lasted until Hayward’s death in 1971. Six months later she married Harriman, then almost 80, caring for him devotedly. The old flame had never died, her son told this writer. “She often called Averell ‘the most beautiful man I’ve ever seen.’”

“Never give in”

Through Harriman and with Churchillian determination, Pamela became immersed in American politics. In 1980 and 1984, the Democrats were in disarray following twin sweeps by Ronald Reagan. Pamela quoted Sir Winston: “In war you can only be killed once, but in politics, many times.” How often he’d been counted out in politics and recovered?

At her home on N Street in Washington she hosted glamorous parties and fundraisers. “She had an ability to attract people around her, and a willingness to try to be a catalyst for the party,” said Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute. “Almost anybody who was asked was going to come to one of the gatherings at her spectacular house.” Her son Winston told me that politics aside, she was “one of the most conservative people I know. She would have brought the same zest had she married Ronald Reagan.”

As those two comments suggest, Pamela Harriman was admired from both sides of the aisle. She supported Clinton in 1992, and was rewarded with the Paris Ambassadorship. Yet at her confirmation hearings she was praised to the skies by the most conservative member of the Foreign Relations Committee, Senator Jesse Helms.

“Darling, this is Pamela…”

She represented it seems the politics of a bygone age, a more Churchillian age. Like her first father-in-law, she saw it as a noble profession, where mutual respect was de rigueur. Years ago I published a piece on Churchill’s 1946 “Iron Curtain” speech by then-Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger. As one might expect, it stressed the Fulton theme of peace through strength. Pamela Harriman wrote a rebuttal emphasizing Churchill’s Fulton title, “the Sinews of Peace.”

Paul Robinson, formerly Ronald Reagan’s ambassador to Canada, read it, disagreed, and confessed that he remained among her greatest admirers. Earlier he had named Harriman and Weinberger co-vice-presidents during his chairmanship of the English-Speaking Union. “They were both superb,” he said. “And very good together—despite everything!”

Shortly before President Clinton arrived in office he proclaimed an admiration for Winston Churchill. I remember sending him, through Pamela Harriman, a blue sweatshirt emblazoned with the Churchill five-cent U.S. commemorative stamp. Delighted, she delivered it herself, and so we made her a pink version.

She telephoned to express her thanks, with the husky opening line that must have thrilled a thousand Washington insiders: “Darling, this is Pamela.” It would have been, and always was, superfluous to ask, “Pamela who?”

“Elegance itself”

Pamela lived life her way—a noble spirit devoted to friends, family and both her countries. Not many people could have journeyed so successfully and far with a formal education that ended at age sixteen.

How did she manage it? She was grace personified, at home equally in Churchill’s air raid shelter or the Élysée Palace. During her term as ambassador, Paris and Washington collided over alleged U.S. espionage, the “Europeanization” of NATO, leadership of the United Nations, peace initiatives in the Middle East, power rivalries in Africa. She handled it all with consummate skill, retaining the respect of her hosts despite those tests.

President Chirac lamented her loss: “To say that she was an exceptional representative of the United States in France does not do justice to her achievement. She lent to our longstanding alliance the radiant strength of her personality. She was elegance itself…a peerless diplomat.”

That old Francophile, her father-in-law, would have smiled.

One thought on “Pamela Beryl Digby Churchill Hayward Harriman 1920-1997”

LOVE the new wide logo at the top of your page!

=

Thank software engineer Ian Langworth in Silicon Valley, who so coded it that the flags stay in the picture regardless of the format from iPhone to big screen. The flags are important because we have so many readers in those countries.

Comments are closed.