Gotcher in the Nye: Winston Churchill on the National Health

Enemy of health

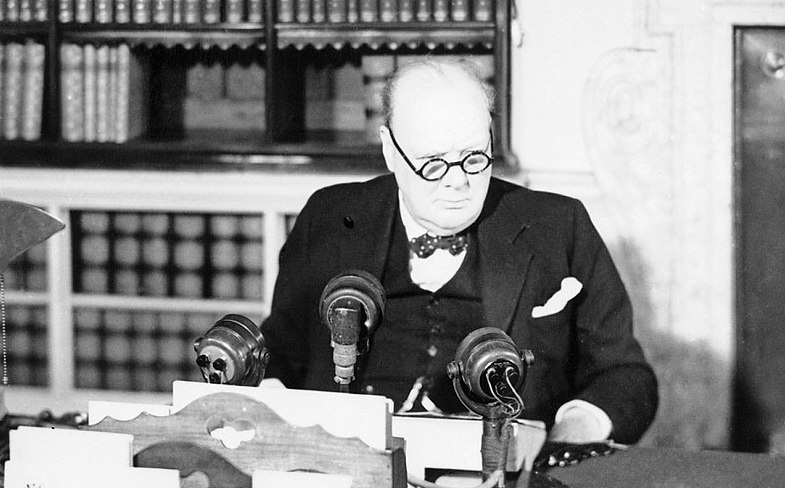

Winston Churchill, the convenient villain in many recent historical accounts, has a new role. He’s now the steadfast opponent of Britain’s National Health Service (NHS), founded by Nye Bevan in 1948.

Churchill, goes the refrain, didn’t care about the health of Britons. (As WSC replied to a Bevan rant in 1944: “I should think it was hardly possible to state the opposite of the truth with more precision.”)

The estimable Robert Colville punctured this nonsense in The Times (London) on March 17th. His highly readable piece is entitled, “Even without Nye, the cult of the NHS is verging on pathological.”

The operative occasion was a new production by Britain’s Royal National Theatre. What’s a correct-thinking producer to offer? “After considering and rejecting Che! The Musical and Johnson’s Inferno,” Colville writes, “you might hit on the idea of a three-hour play about how Nye Bevan single-handedly won the war, invented the NHS and brought civilisation to Britain. Starring Michael Sheen. And then you’d probably scrap the idea for being past the point of parody.”

But no. It’s for real: “The central thesis of Nye, to quote Sheen’s peroration, is that founding the NHS was ‘the most civilised step any country has ever taken’—despite the best efforts of Winston Churchill and the British Medical Association.” The BMA maybe—but not Winston Churchill.

To the Editors of The Times

One shouldn’t write letters to editors. They have the editorial power to skew what you say and make you look silly. However, urged by a prominent British Churchillian, I wrote in praise, not condemnation:

Robert Colville is right to deplore the skewed concepts that render Winston Churchill a diehard opponent of British National Health. As Dr. Nicholas Bosanquet and Andrew Haldenby comprehensively explain, Churchill’s concern for the health of Britons extends from 1945 back through both World Wars to his Liberal reform years 1906-10—when Nye Bevan was still in short trousers. I will not clutter your columns with hyperlinks, but anyone interested may search for ‘Bosanquet Churchill and Health Issues’ on any web browser and learn the truth.

Big mistake. Even though I didn’t provide a link—a real no-no in Letters to the Editor—my British friend pointed out that this was the wrong approach:

They’ll come back to you to ask for your own opinion, as company policy is to not send people to other websites. The killer line you want is that Churchill invented the phrase “national health policy.” This is what you should lead with—and that WSC appointed Beveridge. [Churchill commissioned the Beveridge Report, which recommended a national health service in 1942.]

The Times didn’t bother asking me to revise, so it was a lost cause. However, the handful of readers who actually care may like to know that Churchill advocated national health policies for half a century.

While Nye was in short pants

Health concerns in war and peace

Bosanquet and Haldenby comprehensively reviewed Churchill’s record from those beginnings. In the trenches during the First World War, WSC launched a successful war against lice. A year later as Minister of Munitions, he asked his chief medical officer for “a handbook summarizing the welfare and health issues organized by the Ministry.”

As Minister of War (1919-20), Churchill organized a committee inquiring into treatment of shell-shock. As Chancellor of the Exchequer (1924-29), Churchill introduced widows’ and orphans’ pensions. In 1929 the Local Government Act

transferred functions of Poor Law Guardians and hospitals to local government…. The 1929 Labour Government took credit, but the effective improvements were owed Churchill and Minister of Health Neville Chamberlain. The municipal hospitals were an important part of the Emergency Hospital Service, which began coordination with voluntary hospitals in 1940….

In fact, spending was not reduced during Chamberlain’s and Churchill’s tenure, and more health issues were addressed. Three hundred more ante-natal clinics and 440 more Infant Welfare Centres were opened. The number of practicing midwives increased by 860. The expansion of these local services, mainly staffed by single women on low salaries, was a remarkable gain to health—at low cost.

“The spacious domain of public health”

Churchill’s dominating task from 1940 was winning the war. Yet he found time to commission the 1942 Beveridge Report on social insurance. He then proposed a four-year plan for postwar reconstruction, including what he called “the spacious domain of public health…” On 21 March 1943 he broadcast on the BBC:

I was brought up on the maxim of Lord Beaconsfield which my father was always repeating: “Health and the laws of health.” We must establish on broad and solid foundations a National Health Service. Here let me say there is no finer investment in any community than putting milk into babies. Healthy citizens are the greatest asset any country can have.

In 1943, Bosanquet and Haldenby write, Churchill appointed the social reformer Sir Henry Willink Minister of Health. Willink was asked to produce a Health Service White Paper and draft bill…. Churchill was determined. “The doctors aren’t going to dictate [the future law] to the country,” he told Moran, “they tried that with Lloyd George.”

After the July 1945 election, national health policy fell to Labour and to Nye Bevan. “In other words,” writes Robert Colville, “we owe to Bevan not the National Health Service but this National Health Service—the one that turned the existing profusion of provision into something regimented, standardised, centralised and nationalised.”

Whether this National Health Service is the optimum arrangement is the business of Britons, not Churchill historians. Our job is to uncover the truth, The truth is that for fifty years, Churchill was concerned with and implemented national health policies.

“A squalid nuisance”

If helping in the war is what Nye claims, the National Theatre is going well over the top. Aneurin Bevan was thorn in the side of the wartime government. Not only of Churchill, but Bevan’s own party leader, Deputy Prime Minister Clement Attlee. Colville quotes John Bew’s fine biography of Attlee, Citizen Clem. “Bevan’s index entry starts with, “continually tries to undermine Attlee and his supporters,” and goes on from there.” Bevan railed at both, saying in 1941 that WSC deserved “a good kick” for his leadership. In his newspaper, the Tribune, Bevan mounted attack after attack. But nobody who mattered took him very seriously.

Further reading

“Winston Churchill on Health Care: ‘The Inheritance of All,'” 2013.

“Churchill on Health Care: An Ongoing Discussion,” 2013

“McKinstry’s Churchill and Attlee: A Vanished Age of Political Respect,” 2019.

“Bevan and Trump’s ‘Vermin’ Crack: Nothing New Except the Reaction,” 2023.