Old Victory’s Pride (Extended Review): “Churchill & Son” by Josh Ireland

Churchill & Son by Josh Ireland (New York: Dutton, 2021) 464 pages, $34, Kindle $14.99. First published in The American Spectator, 7 April 2021. I was limited to 1500 words, and so have added certain reflections that occurred since publication (“Just Among Ourselves”). —RML

Josh Ireland’s “Life with Father”

Despite an inauspicious beginning, this is a thoughtful study of a father-son relationship during the storms that rocked a troubled century. Randolph Churchill has now prompted six books—not bad for most Churchills, short of his father (1150 and counting). Josh Ireland here confronts his bittersweet Life with Father, adding fresh insights and thoughtful appraisals to our understanding of the great man and his offspring.

Sir Winston’s cousin Shane Leslie wrote off WSC’s relationship with his father: “Few fathers have done less for their sons. Few sons have done more for their fathers.” A review of Churchill & Son paraphrases: “Few fathers did more for their sons than Winston….Few sons have done less for their fathers than Randolph.”

Both remarks are unjust. Lord Randolph Churchill was a busy politician, wrote Celia and John Lee. Yet he tried “to secure the future of both his boys.” In fact “he went to a good deal of trouble on their behalf, for which he gets no consideration whatsoever.” Winston’s son Randolph gave birth to the longest biography on the planet. Winston S. Churchill is the standard work for generations of scholars. Winston wrote a two-volume tribute to his own father. Both fathers and both sons did much for each other.

Josh Ireland avoids such pat summations. With no apparent axe to grind, he charts the 45-year Winston-Randolph relationship, good, bad and ugly. There are a few errors and skewed judgments, some uneven glosses on events. Yet Ireland largely follows Randolph’s own maxim, “I am interested only in the truth.”

Slow start

The prologue is brief, eloquent, and a good omen, but after the first two chapters of potted background I was ready to toss this book, with its superficial accounts of Lord Randolph’s purported syphilis, Winston’s parental neglect, a Clementine Churchill remindful of a flawed recent biography, and some flawed history. Winston is adamant for war in 1914. He “abandons” the Admiralty to defend Antwerp. Then he invents the Dardanelles operation. Next he plays the “toff in the trenches” of World War I. Later he mortgages a country house in Clementine’s name.

Each of those assertions is wrong, obfuscating broader reality. Churchill tried harder than any minister to save the peace; the Admiralty was ready for war because he made it so; Antwerp’s prolonged defense saved key French ports and he didn’t “abandon” his post, he was sent there. But never mind. What follows is increasingly good. It’s best to skip to Chapter 3, as Randolph reaches maturity—all too precariously.

Growing up with Winston

The boy ages in the Churchill milieu with all its boisterous vivacity and contention, its pantheon of exalted personages. His father betimes accomplishes the work of two men: speeches, articles, books, meetings, hobbies and travel, holding nine ministerial offices within 16 years. Such a mélange is bound to affect any youth growing up in it. Winston, trying to compensate for what he sees as his own father’s neglect, overindulges Randolph. His friend Lord Birkenhead teaches Randolph to drink, and to drink hard. The combination produced oratorical flourishes and boorish overconfidence. Winston contributed by waving his famous cigar for silence whenever Randolph held forth to movers and shakers of the age.

On a 1929 holiday in North America (incorrectly called a lecture tour), Randolph’s circle widened to movie stars and captains of finance and industry. What they saw “was a young man whose self-confidence was so large it appeared it could swallow galaxies whole.” What they missed was the deep sensitivity acquired in his upbringing: he “learned early on to hide this vulnerability…beneath the surface arrogance.”

“A brutal mix of anger and pain”

Josh Ireland often spots crucial contradictions. Randolph was explosive, “his conceit unsupportable.” Yet inwardly he ached for his father’s approval (and his mother’s, much harder to come by). Frequently he tried to resolve the dichotomy with conflict. Winston would say, “I love him very much,” yet his son often reduced him to apoplexy. Randolph would say, “I do so very much love that man, but something always goes wrong between us.” Their relationship was a “brutal mix of anger and pain.”

Winston’s hopes for his son waxed in 1935. That was when Randolph ran for Parliament in Tory-blue Wavertree, Lancashire, challenging the official Conservative candidate. His father, hoping for office in the next Tory government, was initially outraged. But when Randolph began attracting huge crowds, Winston hopefully campaigned for him. Alas Randolph split the Tory vote, handing the seat to Labour. (The book omits the tally: Churchill 24%, Conservative 31%, Labour 35%). Josh Ireland has written the best account yet of this episode—Randolph’s rollicking political apogee. (True, he got in for Preston in 1940, but that was an uncontested seat during the wartime political truce, and he was promptly ejected in 1945. He ran at other times before and after the war, but always lost.)

Father and son were never closer than in the 1930s, each a pariah to the Conservative Party. But Winston could separate politics from personal friendships, and his son could not. “Everyone knew what Winston thought about men like Baldwin,” Ireland writes, but “he was also punctilious about preserving at least the appearance of civility.…Randolph either did not care or could not control himself.”

War and forgetfulness

With war and Winston’s government, Randolph was passed over: his “explosive energy; his willingness to defy anybody, irrespective of their rank or position—were hindrances” at Downing Street. As close as he came was the office of Chamberlain’s toady, the appeaser Horace Wilson. The day Churchill became prime minister, Wilson returned from lunch to find Randolph and Brendan Bracken on his office sofa, smoking huge cigars and glaring at him. Wilson fled, never to return.

Bracken was immediately appointed Churchill’s Minister of Information. A longtime crony, he liked to fan the silly canard that he was Winston’s illegitimate son. Randolph, who was left to join the Army, loved Bracken but called him, with wonderful duality, “my brother the bastard.” Randolph served bravely, in part with Yugoslav partisans. When his father told Marshal Tito he wished he was fighting at his side, Tito remonstrated: “But you have sent us your son!” Tears of emotion rolled down Winston’s cheeks.

Decline, devotion, duty

Randolph’s postwar years were suffused by the grim, monochrome reality of rationed, straitened, impoverished Britain. An Adonis in youth, he aged like Wilde’s Dorian Gray. His 1939 marriage to Pamela Digby went aground in 1946, not least because he knew of her wartime dalliance with Averell Harriman. Ignoring his own countless flings, he unfairly blamed his parents for abetting the affair to court favor with Roosevelt’s envoy. Few of his lady friends could really handle him, but those who did, like his last love Natalie Bevan, assuaged Randolph’s intense craving for affection. They found him impossible; they admired his generosity and courage.

One of Randolph’s great redeeming qualities was a hatred of injustice. In America he voiced outrage over the “barbaric, unlawful negro lynchings in your South,” comparing the “outrageous treatment of your Red Indians” with the “benevolence” of the Indian Raj. Upon landing at Cape Town he was required to state his race. “Damned cheek!” exclaimed Randolph. Fanning an old myth, he proudly declared his “coloured blood” through “the Indian Princess Pocahontas.”

In 1963, when the paparazzi hounded John Profumo following a scandalous affair, Randolph made his home the Profumos’ sanctuary, ordering his staff to bar the media: “There shall be no rot.” (In 1940, Profumo had been the youngest MP to vote against Chamberlain in the division that brought Winston Churchill to power.)

Lord Norwich said, “If you knew Randolph well, you loved him.” Few, says Ireland, saw that side of him. He “staggered around London, littering his path with gratuitous insults….He ruined parties, gate-crashed private dinners, immolated friendships that had lasted for decades….Randolph lived in a cheerful kind of chaos, a function of the self-sabotaging streak in him that had been nurtured by alcohol.”

Randolph’s achievements

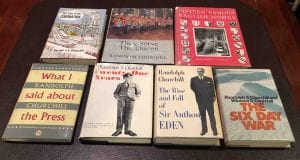

Despite his many handicaps, Randolph was a notable journalist. He covered three wars, wrote 15 books, hundreds of articles, edited seven volumes of his father’s speeches. In 1959, he published his seminal Lord Derby: King of Lancashire. His enthralled father gave him what he’d long wanted: the writing of his biography. It was his chance at redemption, “to create a lasting record of his love and devotion to the man he had loved more than any other person he had ever known. In the process of telling the story of his father’s life, he belatedly gave meaning to his own.”

In 1996 I thought His Father’s Son, by Randolph’s son Winston, the best book about him. I still do, but Churchill & Son deserves to stand with it as the testimony of Josh Ireland, a perceptive outsider. “Randolph Hope and Glory,” as detractors referred to him in the 1930s, emerges as a dynamic speaker, a brilliant journalist, a gallant soldier, a skilled biographer, a frustrated son—and an honest man: as honest about himself, as he was of others. Not so bad an epitaph, after all.

In 1996 his son wrote: “We buried him in Bladon churchyard, beside his grandfather, and his father, whom he loved and revered so deeply. To this day the memory of him lingers on in the hearts of his friends.” I think Randolph would settle for that.

Just among ourselves: personal reflections

Josh Ireland ‘s book reminds us to avoid absolutes when judging Winston Churchill—and his son. The foregoing review was limited to 1500 words—which was right and fitting. But there’s an added aspect for students of the Churchill saga, and it is this:

Personal affairs and family traumas never affected Winston Churchill’s politics—his sense of duty. Despite his perennial concerns over Randolph, nothing diverted him from his responsibility to the nation. (See his essay “Consistency in Politics.”)

In 1935, when Randolph disrupted his plans and ran in Wavertree, Winston was annoyed, then hopeful, then frustrated. The very same year found him encouraging Gandhi after passage of the India Act. Simultaneously he was seeking the truth about German rearmament. No sooner had Randolph stormed out of Chartwell after an argument, than Winston would welcome shadowy Britons and Germans, secretly advising him on Hitler’s war plans. In 1936, setting Randolph-worries aside, his father took the lead in defending Edward VIII in the Abdication crisis—a waste of time that temporarily damaged his cause.

It is true also that Randolph—when he wasn’t “not speaking to Papa”—was able to set personal quarrels aside. Author Celia Lee writes: “Clarissa [Eden, Lady Avon] told me in interview years ago that he was the cleverest of the Churchills—that as a journalist he was able to get into places politicians like Winston could not, and that he was therefore really valuable to his father who never gave him one iota of recognition for the help he’d given him.” We might argue about “cleverest” (his father wrote 40 more books). But Lady Avon’s comments are remarkable, given all the grief Randolph gave her husband, his father’s successor.

Today—when they’re not covering up some scandal—politicians let their family affairs all hang out, like special pleading or virtue-signaling. Not the Churchills.

One thought on “Old Victory’s Pride (Extended Review): “Churchill & Son” by Josh Ireland”

A Churchill scholar writes: “Like you, I nearly binned the book after the first few chapters. I never saw such a sustained and concentrated assault on Lord Randolph and the author quite spoiled his case with repetition. I also, like you, persevered with the book and found it informative and useful in trying to understand what made Randolph tick. Not a man I could ever have liked, I think! And we see Winston all delighted with the birth of a son (exactly as his father was with him, with all the same expressions of affection); then be absent for long spells in his busy political life, and write him a crushing letter about gambling debts as savage as anything Lord Randolph ever wrote to Winston. My general observation is this: Lord Randolph, in all his ‘tyranny and lack of love for his son,’ produced a world class statesman. Winston, in all his gushing love and affection, produced a [fill in the blank]. Perhaps we should be glad not to have been born in the shadow of a mighty oak?”

–

I didn’t know the man, except to get two kind letters from him just before he died, so I can’t be certain about him. Natalie Bevan loved him “despite everything.” Martin Gilbert insisted he had wonderful humanity. That cuts two ways, to channel Auberon Waugh–there were parts of Randolph that were not malignant! Yes, it was a hard thing making your own way in that milieu. —RML

Comments are closed.