Churchill’s Funeral, 50 Years On: His Words Still Call to Us

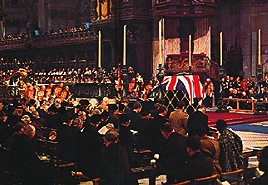

St. Paul’s Cathedral, 30 January 1965….

Most of those reading this knows where they were on 9/11/01. A diminishing number remember where they were on 1/30/65. That was the day we of Sir Winston Churchill’s state funeral.

For me it was a life-changing experience. Suddenly, unforgettably, on a flickering black and white TV screen in Staten Island, N.Y., the huge void of England’s grandest cathedral filled with The Battle Hymn of the Republic. He was, they told us, half-American, an honorary citizen by Act of Congress.

That day was the start of my 50-year career in search of Churchill—of what his greatest biographer, Sir Martin Gilbert, describes as “labouring in the vineyard.”

After the funeral…

…I picked up The Gathering Storm, the first volume of his World War II memoirs, and was snared by what Robert Pilpel called his “roast beef and pewter phrases.” It’s biased, as Churchill admitted—“This is not history; this is my case.” But it is ordered so as to put you at his side for the “great climacterics” that made us what we are today.

Churchill’s life spanned 60 years of prominence unmatched in recent history. Of course he insisted that “nothing surpasses 1940.” That was the year Britain and the Commonwealth—“the old lion with her lion cubs” as he put it, “stood alone against hunters who are armed with deadly weapons.” And fought on until “those who hitherto had been half blind were half ready.”

I soon learned there was more to Churchill than 1940. As Martin Gilbert wrote: “As I open file after file of Churchill’s archive, from his entry into Government in 1905 to his retirement in 1955, I am continually surprised by the truth of his assertions, the modernity of his thought, the originality of his mind, the constructiveness of his proposals, his humanity, and, most remarkable of all, his foresight.” All this his funeral remembered.

Visionary and peacemaker

And what foresight. Churchill predicted mobile phones, jet and rocket travel, 24/7 media, genetic engineering. He warned of the dangers of nuclear war, fifteen years before Einstein wrote his famous letter to Roosevelt on the implications of splitting the atom—this alleged warmonger who said of war: “What vile and utter folly and barbarism it all is.”

This same Churchill negotiated the nonnegotiable—a treaty establishing Irish independence. Michael Collins, one of the IRA revolutionaries who worked with him, declared: “Tell Winston we could have done nothing without him.”

In Cairo he helped draw the boundaries of today’s Middle East—an act for which some say we should not thank him. Yet they established a stable Jordan, which is there yet. Vainly he tried also to create a Kurdish homeland, “to protect the Kurds from some future bully in Iraq.” The optimist in him called for a Jewish homeland: He simply could not understand how the Arabs would not welcome Jews who made “a fertile garden” of the land they both inhabited.

***

He fought and lost over Indian self-government. Then he told Gandhi: “…use the powers that are offered, and make the thing a success.” Decades before, Churchill had defended the Indian minority in South Africa, as he had native Africans. “I have got a good recollection of Mr. Churchill when he was in the Colonial Office,” Gandhi replied, “and somehow or other since then I have held the opinion that I can always rely on his sympathy and goodwill.”

As a young reformer, Churchill campaigned for a “minimum standard” guaranteed by the state: “I see little glory in an Empire which can rule the waves and is unable to flush its sewers.” Yet he instinctively feared socialism: “the philosophy of failure, the creed of ignorance, and the gospel of envy.”

His 15 million published words cover more than war and politics. He wrote history, biography, 3000 speeches, thoughtful essays on the nature of democracy, constitutionalism, liberty and the rule of law. He preserved all his archives for historians to pore over. His words can justify any side of an issue.

“The nature of man”

“Since history never repeats itself, the policies Churchill adopted do not provide ready-made solutions now,” wrote the historian Paul Addison. “But Churchill’s writings and speeches are full of reflections and philosophy that offer food for thought. It is rare to discover in the archives the reflections of a politician on the nature of man.”

I only wish the print and digital media would understand this, and thus generate less rubbish. A few corrective facts: Without Churchill, the 1943 Bengal famine would have been worse. Without him, someone might actually have used poison gas on Iraqi tribesmen or German cities. With him, women got the vote. He opposed it at a time when most British women did, and reconsidered when he saw how much women did for the country in World War I.

This man called for “the harmonious disposition of the world among its peoples.” Yet, we are told, he “fiercely opposed to self-determination.” Was the fierce independence Churchill admired in Canadians, Boers, Zulus, Australians, Sudanese, New Zealanders. Kenyans and Maoris a sham and a façade?

And yet he lives on

Churchill would never win office today, I read during the funeral anniversary. A “ruthless egotist,” he “would struggle to be elected.” Was there a great political figure who was not an egotist? No one elected him in 1940. Nobody else wanted the job. And Churchill’s wartime relationships with Allies and the military were very stuff of compromise.

Why does Churchill defy such attacks generations after his funeral? Because, I think, Winston Churchill stands for something. For certain critical human possibilities that are always worth bringing to the attention of thoughtful people. Why? In order to perpetuate things worth perpetuating: Love of country. The fraternal relationship of the Great Democracies. Their heritage of law, language and literature. Our thirst for liberty. Our invincibility when we work together for just causes.

Across the years

In the time since his funeral I learned much of Churchill’s life and thought. The eerie relevancy of his challenges and experiences still call to us across the years. There will always be scoffers, who portray him as a one-dimensional, a man of war, an anachronism. “In doing so, it is they who are the losers,” Martin Gilbert concluded. “For he was a man of quality: a good guide for our troubled present, and for the generations now reaching adulthood.”

Some who miss him lament that there are no Churchills today. Perhaps such leaders emerge only in life or death emergencies. We may be facing one again.

***

This article first appeared in The Weekly Standard online, 23 January 2015.

For the famous rendering of The Battle Hymn of the Republic by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, click here.