Nashville (4). Churchill as Warmonger in World War I

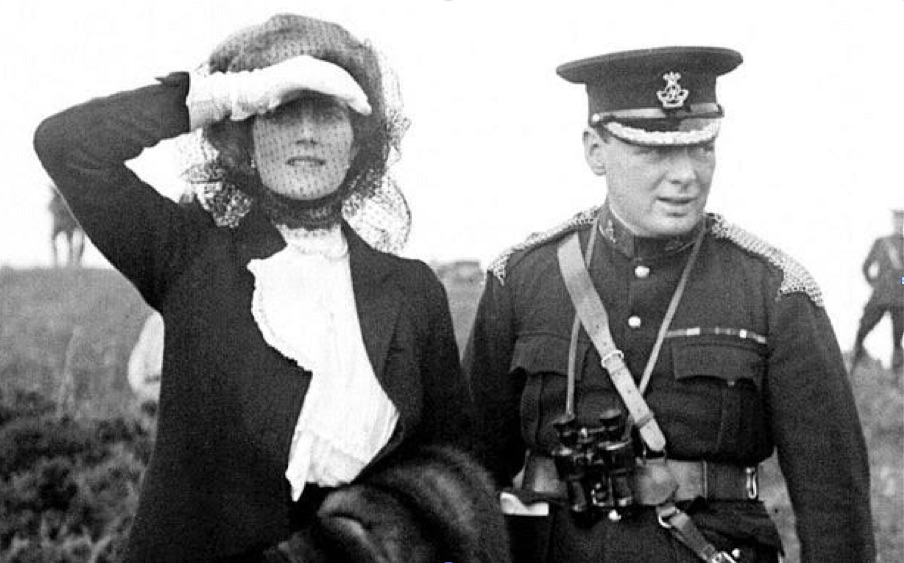

“Winston…has got on all his war-paint” (Asquith)

In 1914, the Great War arrives, and fables about Churchill multiply. A popular one, kept alive by pundits and historians, alike, is that Churchill led the warmonger party into World War I. Remarks to the Churchill Society of Tennessee, Nashville, 14 October 2017. Continued from Part 3...

Patrick J. Buchanan is an affable tory who wrote speeches for Nixon and ran quixotic campaigns for President of the U.S. three times in 1992-2000. (I voted for him once!) He’s an effective contrarian, and his debating skills are renowned. I assisted Pat researching facts (as opposed to fiction) for his book, Churchill, Hitler and the Unnecessary War. He has a real tick about Sir Winston, and I knew his book would be critical. But he’s such a charming gent that it was fun to correspond. We became friends, disagreeing utterly. We exchanged books with little digs at each other in the inscriptions.

I too wrote a book about the coming of World War II, Churchill and the Avoidable War. Of course I sent one to Pat, saying I marshaled more facts in 94 pages than he did in 546. As Churchill said of Stanley Baldwin, “Occasionally he stumbled over the truth, but hastily picked himself up and hurried on as if nothing had happened.”

Pat’s case was that World War II would have been unnecessary if nobody listened to Churchill—ever. Heck, even World War I might have been dodged (and Nazism and communism with it), if Churchill wasn’t around to play the warmonger in 1914.

Warmonger Winston

Here is the partial quote used to label Churchill a warmonger. It’s from a letter to his wife on 4 August 1914: “Everything tends towards catastrophe & collapse. I am interested, geared-up & happy….”

But the rest of that paragraph (which Pat omits) casts an entirely different light:

…Is it not horrible to be built like that? The preparations have a hideous fascination for me. I pray to God to forgive me for such fearful moods of levity. Yet I would do my best for peace, and nothing would induce me wrongfully to strike the blow.

The historian Max Hastings, in his comprehensive account, Catastrophe 1914, is sadly on Buchanan’s side. And Hastings adds another red herring. “Churchill,” he writes, “adopted a shamelessly cynical view….‘if war was inevitable this was by far the most favourable opportunity and the only one that would bring France, Russia and ourselves together….’”

But that remark is not from 1914. It’s from a 1925 letter from Churchill to Lord Beaverbrook, commenting on Beaverbrook’s war memoirs—and Hastings omits the rest of it:

I should not like that put in a way that would suggest I wished for war and was glad when the decisive steps were taken. I was only glad that they were taken in circumstances so favourable.

Deleting this casts Churchill in a very different position than the one he actually took.

Not Warmonger but Peacemaker

In reality Churchill tried to save the peace. He did two things. First, in 1912, he proposed a “Holiday” in British and German battleship construction. This was greeted with derision by Kaiser Wilhelm and his naval chief, Admiral von Tirpitz, who were bent on challenging the Royal Navy.

The second was his last-ditch proposal for what could have been the world’s first summit conference. “I wondered,” he wrote his wife in late July,

whether those stupid Kings and Emperors could not assemble together and revivify kingship by saving the nations from hell but we all drift on in a kind of dull cataleptic trance. As if it was somebody else’s operation!

He proposed this in cabinet and the idea actually reached Berlin. The Germans rejected it, saying it would amount to “a court of arbitration.”

Yet we still have these skewed pictures of Churchill in 1914, spread by everyone from pundits to seasoned historians. The truth is that Churchill strove longer and harder than any British statesman to prevent war, which he hated and feared all his life.

N.B.: Time prevented complete documentation of Churchill’s efforts to preserve the peace in this speech. They may be read and considered in full, with extensive endnotes, in Winston Churchill, Myth and Reality.

Between the Wars…

More Churchill fables pile up between the wars. Churchill was an alcoholic. He flip-flopped over Bolshevism. All Jews, he wrote, were communists. He hated Gandhi. A closet fascist, he fancied Mussolini. But no tall tale is quite so pernicious as the idea, maintained now for two decades, that Churchill admired Hitler.

Continued in Part 5… Winston Churchill, Myth and Reality is now available in paperback, with a lower price for the Kindle edition. Click here.