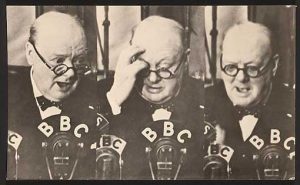

Churchill on the Broadcast

The question arises, has anything been written on Churchill’s radio technique? Did he treat radio differently from other kinds of public speaking? How quickly did he take to the broadcast?

“The Art of the Microphone”

An excellent piece on this subject was by Richard Dimbleby (1913-1965), the BBC’s first war correspondent and later its leading TV news commentator. His “Churchill the Broadcaster” is in Charles Eade, ed., Churchill by his Contemporaries (London: Hutchinson, 1953). Old as it is, the book remains a comprehensive set of essays of the many specialized attributes of WSC.

Dimbleby offers four areas of discussion: the technical background, the drama of World War II, the factual material, and Churchill’s methods of delivery.

Dimbleby provides detail about how the BBC handled the wartime broadcast, which originated in vastly different places, from commodious Chequers (the PM’s official country residence) to the cramped confines of the underground Cabinet War Rooms.

“Be Quiet—Churchill’s Broadcasting”

“Churchill had a ready-made, keen, sympathetic audience,” Dimbleby wrote:

He had created enormous national confidence in himself. The great majority of the people—there were, of course, his opponents—trusted him, supported him and were avid for anything he had to say, even if his major promises were of “blood, toil tears and sweat.” Here, they felt, was a man who would say what had to be said, however unpleasant it was, and who would always hold out some hope of better things.

Of course the man himself was deeply conscious of this waiting audience, of the fact that he was speaking with authority, with a full private knowledge of the truth….

It was not only in Britain or the countries of her allies that people hung on Churchill’s words. I was told recently by a German broadcasting official who worked at Hamburg during the war that he walked into the offices one night and found normal work at a standstill. Even William Joyce, then in the full foul flood of his radio oratory as “Haw Haw,” was away from his desk. Asking what was up, the official was told to be quiet—“Churchill’s broadcasting.”

Broadcast Consistency

Churchill’s “magic of word and phrase, the forceful delivery, the mastery of language that made each of his great wartime broadcasts a pageant,” Dimbleby continued. Ironically, Churchill’s transgressions of the rules were what made him so good:

…he breaks every accepted rule of broadcasting….He drops his voice where he should raise it, he alters the recognised system of punctuation to suit himself (some of his scripts were virtually unintelligible to anyone else), he speaks much of the time with anything but clarity. Yet such is his power as an orator, and such his feeling of the public pulse, that during the war years he was sure of a silent and appreciative audience of millions, following every word and phrase with relish.

Churchill was also consistent over the years. His patterns of speech never changed. During a lecture, Dimbleby played Churchill’s very first 1909 published recording, on the Liberal Government’s budget:

There was no need for me to announce the speaker, for the first half-dozen words established his identity. The passage of nearly half a century has made virtually no difference to the voice, except to deepen and thicken it slightly. The same faint sing-song is there and the same lilting cadences, though there is never a cadence where you might expect it, at the end of a sentence. Generally the voice goes up, leaving the listener with the feeling that the sentence has not really ended at all.

These techniques were features of the special talent Churchill laid on his palimpsest of oratory. What was the real key? Dimbleby said it was “mastery of the English language.” Churchill loved words, especially in broadcasts, when he was not there to be seen to gesture or to grimace to aid his delivery. It was all based on words alone:

“Purblind Worldlings”

The historian will not fail to note that description of Mussolini as “this whipped jackal, frisking at the side of the German tiger…..” Von Ribbentrop was “that prodigious contortionist.” Those who dared to ask what Britain was fighting for were “thoughtless dilettanti or purblind worldlings.”

The actions of Russia in October 1939, as they seemed Churchill, were “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” But there was no puzzlement about the character of “Herr Hitler and his group of wicked men, whose hands are stained with blood and soiled with corruption.” Then there were the neutral States, each one of which “hopes that if he feeds the crocodile enough, the crocodile will eat him last.” The crocodile was seen in another form when it turned upon Russia in June 1941…. “Now this bloodthirsty guttersnipe must launch his mechanised armies upon new fields of slaughter, pillage and devastation.”

Those were fighting words, Dimbleby continued: words that made men and women in the midst of all-out war chuckle, knowing they were “exactly what they themselves would have liked to say”:

And when Britain stood alone after the fall of France, how magnificent was that sentence, “Faith is given to us, to help and comfort us when we stand in awe before the unfurling scroll of human destiny.”

This was surely the art of the microphone, or the art of the orator adapted to the microphone, at a level higher than had ever been reached before or has ever been attained since.

Whatever have been Churchill’s fate in the years after the war, Dimbleby concluded—whatever public utterances he might yet make— “he will always be remembered by the people of Britain for the way in which he spoke to them in their homes when death was very near.”

Bibliography of Recordings

The first-ever bibliography of Churchill’s recordings (which include speeches and readings from his war memoirs) has been posted by the Hillsdale College Churchill Project, compiled by Ronald Cohen, author of the seminal Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill.

Mr. Cohen’s new list includes the 1909 Budget speech Dimbleby alluded to, which was published in the then-new flat disc format that, in the 1920s, replaced the roller form of recording. That was, of course, a speech, not a broadcast. Broadcasting in Britain began in June 1920.

Churchill’s first broadcast, his hilarious speech about “St. George and the Dragon,” for St. George’s Day 1933, may be the earliest speech to be broadcast and recorded. Part of his remarks can be heard online: click here. I can’t help reflecting how relevant they seem, with relation to the recent nuclear deal with Iran.

2 thoughts on “Churchill on the Broadcast”

In fact that “quotation” is in my book—in the appendix on false quotes (“Red Herrings”). The accompanying note reads: “An example of how hearsay becomes a quotation. This first appearance was in Duff Cooper’s memoirs. Sure enough, it appeared as a direct quotation in the highly unreliable The Private Lives of Winston Churchill, and was repeated by Sarvepalli Gopal in “Churchill and India” (Blake & Louis, Churchill: A Major New Assessment (1993, 459).”

You’re a real searcher for the truth, aren’t you?

Richard, you lying little piece of [expletives deleted]. Churchill proclaimed in 1920 that Gandhi “ought to be lain bound hand and foot at the gates of Delhi, and then trampled on by an enormous elephant with the new Viceroy seated on its back.”

Comments are closed.