Churchill 101: Three Reasons to Learn about Sir Winston

Originally written for and published by the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. This is one of several forthcoming articles intended to encourage younger readers to learn about Churchill. Reader comment, suggestions of further points to make, and other articles on the same theme, would be appreciated.

_________

Learn …

Who was Winston Churchill? Why, half a century since his death, is he the most quoted historical figure? Scholars know the answers. Do you? Why does it matter?

It matters because Churchill continues to offer guidance and example today. His indomitable courage, his ability to communicate, his knowledge of history, his political precepts, are as valuable now as they were in his time.

Courage and resolution

Churchill himself said “nothing surpasses 1940.” We must look there for to learn of his greatest accomplishment. Without him the world today would be unrecognizable: dark, impoverished, tortured. Churchill didn’t win the Second World War. That took more than he alone could offer. His triumphant achievement was not losing it.

Churchill did that in two ways: pursuing the paramount goal to the exclusion of all others; and communicating that goal to a baffled and frightened world.

The great movements that underlie history are the development of science, industry, culture, social and political structures, wrote Charles Krauthammer:

These are undeniably powerful, almost determinant. Yet every once in a while, a single person arises without whom everything would be different…. The originality of the 20th century surely lay in its politics. It invented the police state and the command economy, mass mobilization and mass propaganda, mechanized murder and routinized terror—a breathtaking catalog of political creativity. And the 20th is a single story because history saw fit to lodge the entire episode in a single century. Totalitarianism turned out to be a cul-de-sac. It came and went. It has a beginning and an end, 1917 and 1991, a run of seventy-five years neatly nestled into the last century. That is our story.

And who is the hero of that story? Who slew the dragon? Yes, it was the ordinary man and woman, the taxpayer, the grunt who fought and won the wars. True, it was America and its allies. Indeed, it was the great leaders: Roosevelt, de Gaulle, Adenauer, Truman, John Paul II, Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan. But above all, victory required one man without whom the fight would have been lost at the beginning. It required Winston Churchill.

Learn more: Winston Churchill’s War Leadership, by Martin Gilbert; Churchill and War, by Geoffrey Best.

Right and freedom

Almost all his life, Churchill’s quarrel was with tyranny. But singularly among politicians of his time, he saw the future—and its implications for good or ill. Churchill predicted today’s age of instant communications. He foresaw the nuclear age, the mobile phone, social media, genetic engineering. He feared the challenge to free government through what he called “Mass Effects on Modern Life.” It is useful to learn how he expressed these warnings, which still apply.

As early as 1908, Churchill’s ideas, speeches and legislative accomplishments produced pioneering reforms in the social structure. His aim was to reform what was bad and to preserve what was good, without disrupting the enterprise that produces the wherewithal to make life worth living. That is still a worthy goal.

* * *

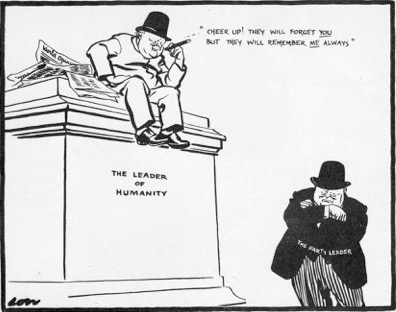

At the same time, Churchill foresaw the all-powerful administrative state. Many an advance in science, technology and communication, Churchill argued, “suppresses the individual achievement.” He deplored the rise of the collective at the expense of the individual: “Is not mankind already escaping from the control of individuals? Are not our affairs increasingly being settled by mass processes? Are not modern conditions—at any rate throughout the English-speaking communities—hostile to the development of outstanding personalities and to their influence upon events; and lastly if this be true, will it be for our greater good and glory?” Today such questions merit examination by thoughtful people.

The newspapers do a lot of thinking for us, Churchill wrote. Substitute “media” for “newspapers” and he could be speaking today. He particularly worried about the superficiality of media. True, it provides “a tremendous educating process. But it is an education which passes in at one ear and out at the other. It is an education at once universal and superficial.” Such a process, taken to its ultimate ends, would produce “standardized citizens, all equipped with regulation opinions, prejudices and sentiments, according to their class or party.”

These considerations alone, writes Larry Arnn,

offer ample practical reasons to know Churchill’s story; but there are other reasons beyond the manifestly practical. Justice and the duty to pursue it are central to true statesmanship. It is certainly worth our time to consider how Churchill, who held to that idea as strongly as any, understood his and his country’s purposes and navigated toward them.

Learn more: Churchill’s Political Philosophy, by Martin Gilbert; Churchill’s Trial: Winston Churchill and the Challenge to Free Government, by Larry P. Arnn.

Magnanimity and generosity

Another quality worthy to learn was Churchill’s magnanimity. He was not a hater. “I have always urged fighting wars and other contentions with might and main till overwhelming victory,” he said, “and then offering the hand of friendship to the vanquished.” He proved this repeatedly.

As a young statesman Churchill fostered a generous peace with the Boers after their defeat in the Boer War. In 1918, he urged (vainly) that shiploads of food be sent to blockaded Germany. He fought the 1926 General Strike, then argued for redress of strikers’ grievances. His hate for the Germans in World War II “died with their surrender.”

* * *

He held the same attitude toward individuals—something we can only wish for among today’s politicians. Admiral Fisher nearly destroyed his career in 1915; a year later Churchill advocated Fisher’s return to the Admiralty. In 1945 the socialist Clement Attlee inflicted his greatest political defeat. Yet when confronted with jokes at Attlee’s expense, Churchill refused to be drawn into lampooning a man he described as a “gallant servant of his country.” In the 1930s he fought a bill granting India greater independence, and then urged the Indian leader Gandhi to “make the most of it,” and promised to see that India would get “much more.”

His eulogies to Neville Chamberlain and Lloyd George were masterful in their generosity, Andrew Roberts wrote: “He did not believe in vengeance against domestic political opponents, but rather in what he called, ‘A judicious and thrifty disposal of bile.’”

This was a rare quality, even then. It remains an example worth imitating. To those who had wronged him in the past Churchill would say, “time ends all things,” or “the past is dead.” In 1940, having finally risen to the pinnacle, he warned critics of his predecessors: “If we open a quarrel between the past and the present we shall find that we have lost the future.”

Learn more: Churchill as Peacemaker, James W. Muller, ed.; Great Contemporaries: Churchill Reflects on FDR, Hitler, Kipling, Chaplin, Balfour, and Other Giants of His Age, by Winston S. Churchill.

“A man of quality”

We do tend to be discouraged about how things are going—although in our time, they haven’t gone all that badly. The fall of the Soviet Union, the prevalence of free market economics, were not things people would bet on forty years ago. Churchill saw them coming twenty years earlier than that. He was always the optimist. Humanity, he believed, was not going to destroy itself.

“In every sphere of human endeavour, Churchill foresaw the dangers and potential for evil,” wrote Martin Gilbert:

Many of those dangers are our dangers today. He also pointed the way forward to our solutions—for tomorrow. That is why it is useful to learn about his life. Some writers portray him as a figure of the past, an anachronism, a grotesque. In doing so, it is they who are the losers, for he was a man of quality: a good guide for our troubled decade and for the generations now reaching adulthood.

2 thoughts on “Churchill 101: Three Reasons to Learn about Sir Winston”

Thanks so much. Several typos corrected and some additions made to Krauathammer’s remarks.

Richard: This is, in two words, SIMPLY GREAT! I will be sharing the full article with my extended family as compelling rationale for my Churchill addiction. Who knows, maybe they will catch the bug themselves.

Comments are closed.