Myths of Dear Benito: Churchill’s Alleged Mussolini Complex

Excerpted from “Churchill Always Admired and Offered Peace to Benito Mussolini,” written for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original article with endnotes, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, and enter your email in the box “Stay in touch with us.” We never spam you and your identity remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Lawgiver to Jackal, 1927-1940

The art of the out-of-context quote is practiced frequently over Churchill’s supposed views of Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini. (“Why do you spell out all his names? He doesn’t deserve them,” a pedantic proofreader once asked me. I don’t know. In view of how he ended up, hanging upside down, it’s an irony.)

Did Winston Churchill admire the fascist dictator? With careful editing, one can try to sell this argument. Churchill once praised Italy’s “renowned Chief, with his “Roman genius…the greatest lawgiver among living men.” Little more than a decade later, Il Duce had become a “jackal” in Churchill’s vernacular. What a hypocrite! Perhaps, perhaps not.

Churchill’s early words sound damning, given what we know of Dear Benito in retrospect. And the critics pounced. “Before the war, Churchill offered Il Duce a deal,” wrote Clive Irving in the Daily Beast. “After the war, British intelligence tried to destroy their correspondence…. When Churchill became prime minister in May 1940 he tried, in a series of letters, to dissuade Mussolini from joining the Axis powers. He was ignored.”

This mixes much that is true with much that is trite, as Arthur Balfour once quipped: “The problem is that what’s true is trite, and what’s not trite is not true.”

Caro Benito

One of Churchill’s responsibilities as Chancellor of the Exchequer (1925-29) was recouping foreign war debts. Italy owed £600 million (£30 billion today). Churchill agreed to defer payments until 1930. Il Duce Benito sent “the warmest expressions of gratitude” and offered Churchill a decoration. Thanks but no, said WSC. (Imagine if that was among Churchill’s medals.)

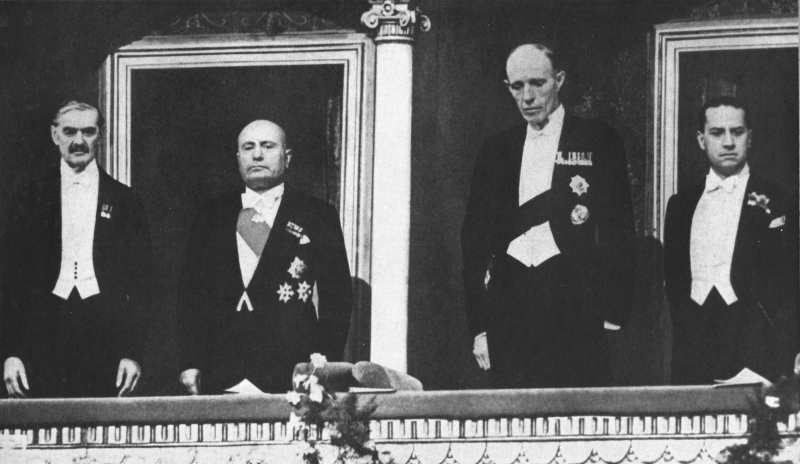

In Rome in January 1927, Churchill had two brief meetings with Mussolini. At a press conference afterward, Churchill told Italian journalists:

I could not help being charmed, like so many other people have been, by his gentle and simple bearing and by his calm, detached poise in spite of so many burdens. If I had been an Italian, I am sure that I should have been whole-heartedly with you from start to finish in your triumphant struggle against the bestial appetites and passions of Leninism.

That remark was in part standard diplomatic boilerplate. But—cropped after “finish”—it has been used to damn Churchill as pro-fascist. In context, he clearly referred to the Italians, not the British.

Also, you tend to say polite things about a foreign leader when he has promised to pay back a lot of money. What Churchill wanted for Italy was to stand up to Bolshevism—which in 1927 he feared more than anything.

Rome versus Berlin?

Churchill always thought in terms of coalitions, so the coming of Hitler made him ponder Benito Mussolini as a potential ally. Hitler’s plans for Austria, and perhaps Trieste, did not seem in Italy’s interest. The diplomatic situation became trickier in 1935 when Mussolini invaded Ethiopia (Abyssinia). On 26 September, Churchill said Britain would support League of Nations sanctions and an arms embargo.

But Churchill remained ambivalent about challenging the Italian dictator. “I would never have encouraged Britain to make a breach with him about Abyssinia,” he wrote, “or roused the League of Nations against him unless we were prepared to go to war in the last extreme.”

In May 1937 he proposed a Mediterranean pact against “further aggression” by Hitler, hoping Mussolini might join. By then, however, the breach was far advanced. Caro Benito would not forgive Britain’s support of sanctions.

Trying to hold Italy

Was Churchill’s attitude toward Mussolini inconsistent or realistic? Italy’s aggression was directed far from pivotal Europe. On that continent, Churchill considered Germany a greater menace than Russia. Accordingly, he courted both Rome and Moscow, often at the same time. It didn’t help that neither liked the other.

In early 1939, Churchill offered Soviet Ambassador Ivan Maisky proposals for collective security against Hitler. Russia, Maisky declared, would “not come in to any coalition which includes Italy…. [Russia would have] no confidence in France or ourselves if [you] start flirting with Italy.”

Churchill shot back: “[T]he main enemy is Germany.” It was always a mistake, he added, “to allow one’s enemies to acquire even unreliable allies.”

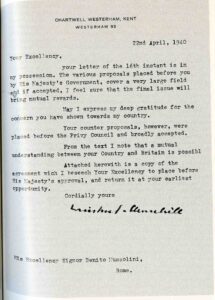

As Prime Minister in May 1940, Churchill wrote his first and only letter to Benito Mussolini. A “river of blood” threatened to engulf Britain and Italy, he wrote. “I have never been the enemy of Italian greatness.” He was not writing in a “spirit of weakness,” although of course he was. Mussolini’s answer was abrupt:

Without going back very far in time, I remind you of the initiative taken in 1935 by your Government to organise at Geneva sanctions against Italy, engaged in securing for herself a small space in the African sun without causing the slightest injury to your interests and territories or those of others. I remind you also of the real and actual state of servitude in which Italy finds herself in her own sea…. the same sense of honor and of respect for engagements assumed in the Italian-German Treaty guides Italian policy today and tomorrow in the face of any event whatsoever.”

Fake “peace feelers”

On 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on France and Britain. Ironically, Benito Mussolini was the first major wartime figure to fall. Three years later the Fascist Grand Council repudiated their leader of two decades. “The keystone of the Fascist arch has crumbled,” Churchill told the House of Commons. Long before then, Mussolini had long gone from “renowned chief” to “hyena” in the Churchill lexicon.

Was Churchill impressed by the Mussolini of the 1920s and 1930s? Many people were, although a realist might conclude that Churchill said what he did in British interests. Churchill redacted little from his archives; researchers can pore over a million documents searching for smoking guns. One quest involves the so-called Churchill-Mussolini “peace correspondence,” which has long been rumored to exist—somewhere.

Three supposed letters from Churchill to Mussolini, with offers of support provided Italy left the Axis, are mentioned at least since 1954, when Giovannino Guareschi published the purported texts in his magazine Candido. Guareschi was later prosecuted and imprisoned for publishing forged letters by Alcide De Gasperi, Italy’s 1945-53 prime minister. The Churchill letters were also alluded to by Renzo De Felice, official historian of fascism and biographer of Mussolini. De Felice died in 1996, his evidence unpublished.

In 1985 the most celebrated conspiracist, Arrigo Petacco, reproduced copies of the three letters (two dated 1940, one 1945). Ignoring their typos and stilted English, even the casual would find it difficult to believe they are genuine. The Italian researcher Patrizio Giangreco reviewed them in 2010, proving them obvious fakes. (See “Further reading” below.)

“La pista inglese”

The Churchill Archives hold only one Churchill letter to Mussolini—that of 16 May 1940—and Mussolini’s negative reply two days later. But the conspiracists persist. “Although there would have been copies in London of the Churchill-Mussolini exchanges,” wrote Clive Irving, “none has ever turned up and in April 1945, somebody in London was very anxious that Mussolini’s copies should never see the light of day.” Italian historians dubbed this scenario La pista inglese (The English trail).

In September 1945, the myth continues, Churchill himself joined the search. He traveled to Lake Como, an area that had been controlled by Il Duce’s rump Republic of Salò, staying at the “Villa Aprexin.” A photograph was taken and published in R.G. Grant’s Churchill: An Illustrated Biography. Ostensibly on a painting holiday, Churchill’s real purpose was to retrieve his Mussolini letters. (With so many people out to steal the correspondence, it’s amazing that none ever came up with it.)

The problem with all this, as Giangreco noted, is that Churchill’s villa, where he stayed from 2 to 19 September, was “La Rosa.” The photograph of him painting nearby is the one in Grant’s book. From La Rosa, Churchill went to Villa Pirelli near Genoa, and from there to Monte Carlo and the French Riviera.

Conspiracies upon conspiracies

Still the beat continued, Clive Irving fanning it in 2015: En route to Lake Como, Irving wrote, Churchill stopped in Milan to stand bareheaded at Mussolini’s unmarked grave! No evidence is offered, nor is there any. Churchill flew from London September 2nd and arrived in Como the same day.

Irving claimed Churchill flew to Milan under the cover name “Colonel Warden,” which he says was the pilot’s name. Actually that was Churchill’s code name throughout the war, derived from his title, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports.

Churchill’s villa at Como, Irving continued, was “owned by none other than Guido Donegani…an industrialist and Fascist collaborator,” who was “interrogated by British Intelligence and later released.” Donegani supposedly handed him the incriminating letters, papers or diaries—they are variously described.

Irving claimed that official biographer Martin Gilbert “concluded that the correspondence had been retrieved and handed over to Churchill, but it never turned up in the Churchill archives and was never seen again.”

Martin Gilbert dismissed the whole idea of secret Mussolini correspondence. His account does not mention Donegani, who died in 1947. If Donegani did own Villa La Rosa, there is no evidence Churchill ever met him. The day after he arrived, Churchill wrote his wife that the villa belonged to “one of Mussolini’s rich commerçants who had fled, whither is not known.”

“You haven’t looked hard enough”

Churchill admitted in his memoirs that he had once expressed admiration for Mussolini as a bulwark against Bolshevism. He distinguished between different types of fascism. Unequivocally opposed to Nazism, he was also anti-fascist in British affairs. He was uncritical of fascism in Italy—until Mussolini fell in with Hitler and declared war in June 1940. The Prime Minister who would have “no truce or parley” with Hitler and his “grizzly gang” would never have supported the Italian “frisking up at the side of the German tiger.”

Possibly the best rejoinder to all this is by the historian Andrew Roberts:

Leaving aside the fact that Churchill would not at that stage [1940-43] have wanted or needed peace with Mussolini, one charge goes that the relevant documents are in a waterproof bag at the bottom of Lake Como. So, when one takes issue with them, the conspiracy theorists say “go and look.” Of course, if you don’t find anything, they just say, “you haven’t looked hard enough.”

Further reading

Patrizio Romano Giangreco, “Review: Mistero Churchill by Roberto Festorazzi,” 2016.

“The Churchill-Mussolini Non-Letters,” 2015

“Mussolini’s Consolation” (Churchill Quotes),” 2012

“Cole Porter and a Vanished Culture: Brewster and Mussolini,” 2020