Chequered Past: Of England and the Automobile

Q: Do you still write about cars?

A colleague in Devon, introduced over Churchill subjects, writes: “I’m curious about your motor writing. I’m a RoSPA qualified advanced driver and had one of the first righthand drive Audi Quattros. Our local group had a fascinating talk by an automobile writer who reviewed 502 cars and wrote the book, he said, on the Mini.”

A: The automobile: still plugging along

Yes, I still write feature articles for Collectible Automobile (US) and The Automobile (UK). I also write the value guides for Collectible Automobile. The latter are very droll: “Would you really pay $50,000 for one of these? … The instruments are down by your knees, where you won’t have to look at them.” (Which is why I write those columns without a byline.) Recent automobile articles are archived here. To access websites for the two magazines click CA or TA.

Two subjects—Churchill and the automobile—have kept me occupied most of my life. For an article that combines them both, see “Churchill’s Motorcars,” archived in three parts beginning here.

My relationship with Publications International, publishers of Consumer Guide and Collectible Automobile, is the longest of my career. It’s been fun all the way. It began in 1977, when I co-authored with Jeffrey Godshall a thin little illustrated book called 1957 Cars. Jeff was a talented car designer and writer, lost to us in 2019, greatly missed by the autoholic fraternity.

You remember 1957…. No? Well, too bad. That was a very good year for the automobile. Think Everly Brothers: “And he’s got a new Fifty-seven too.” (I can’t find a copy of 1957 Cars anywhere, neither on Amazon nor Bookfinder.com.)

The Mini and its descendants

Ah the Mini. A brilliant idea by the inimitable Alec Issigonis, failed in execution, or at least in marketing. It was never really right for the American market, but a huge success in Europe. It led in turn to the somewhat larger BMC 1100 (ADO16), and then to the Maxi, which failed badly.

A friend owned a derivative, the Vanden Plas Princess 1100: a “Watch Charm Rolls.” Outside it was mostly stock 1100, but the inside was swathed in Connolly leather, wool carpets and burled walnut. It was a little gem—overpriced and completely wide of the market.

The more basic version of ADO16, sold as the MG 1100 in the USA, briefly bid to rival Volkswagen. The Bug was reaching its maximum appeal when the 1100 arrived in 1962. The British rival had four doors, much more room inside, more luggage capacity, and similar fuel economy. But right away there were problems.

Debacles

Kjell Qvale, who sold many British cars in California and liked them particularly, told us a sad story. The engineers back in England, he said, were baffled by the 1100’s service problems.

The cars were burning out engines in Los Angeles and burning up clutches in San Francisco. Why such opposite problems in two cities so close on the map? They’d never set foot in the United States.

So it went with the British industry, whose approach to foreign markets was often myopic.

So it went with the British industry, whose approach to foreign markets was often myopic.

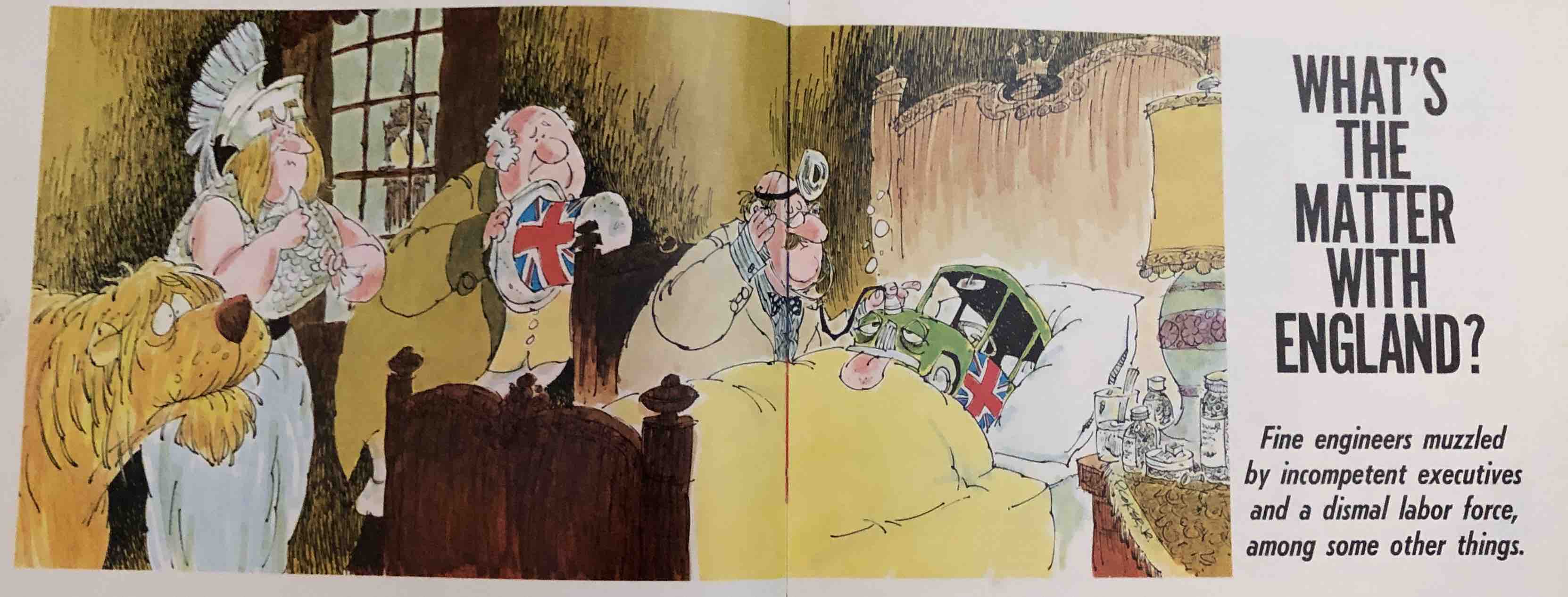

In 1973 at Automobile Quarterly, we published a panel discussion on UK automaking—what was left of it. British Leyland were offended—scroll to our title spread here.

To dispute our conclusions and show how bright they were, Leyland organized a 1974 press tour of factories. I remember my first visit to MG at Abingdon-on-Thames. It was like something out of Dickens.

(The odd thing was that the American industry started doing the same dumb things a few years later, with very similar results.)

An English obsession

That was the first of twenty trips to the UK. It sounds irreligious, but I’ve never been able to relate to Ferraris, possibly because I could never afford one. Give me a quirky English rig like the Sunbeam Harrington Le Mans, with an interesting pedigree and a shape you don’t see every day.

There’s something about the smell of leather and wool, the way the rain beads on the bonnet, that reminds you of the days when almost anybody in England could build a sports car, and most of them did. A worker in Coventry once said to me about the Triumph TR6: “It rides hard and smells of oil, mate. They just don’t make cars like that any more.”

In 1977, we brought “Babs,” the Land Speed Record car, back Pendine Sands on the 50th anniversary of the crash and death of the great Welsh racing driver John Godfrey Parry Thomas. (After the crash Babs was buried in the sand. Years later she was dug up and restored by an intrepid Welshman, Owen Wyn Owen.)

We hosted automotive tours of England, and were welcomed at fabled shrines like Morgan and Aston Martin Lagonda and Rolls-Royce. Grand memories.

A vanished world

My friend above wrote from the West Country, which I knew well, having explored and rented cottages from Dorset to Somerset, Devon to Cornwall. We had close friends in Bristol, who co-founded the Triumph Mayflower Club. There I visited a “niche manufacturer” by the same name, Bristol Motors, run by an affable gent with the misleading name of Anthony Crook.

Bristol had only one showroom, in Kensington High Street, London. Its cars were built by hand: big, potent gran turismos most often powered by American V-8s. Tony Crook sold out in 1997 and the firm struggled on into receivership in 2020. He was kind man and a brilliant innovator who loved the automobile.

Back in the 70s and early 80s, Britain was a driver’s paradise. The roads, unhampered by extremes of temperature as in the USA, were billiard table smooth and immaculate. You could drive as fast as was reasonable and (if sober) overtake on curves.

Back in the 70s and early 80s, Britain was a driver’s paradise. The roads, unhampered by extremes of temperature as in the USA, were billiard table smooth and immaculate. You could drive as fast as was reasonable and (if sober) overtake on curves.

Over the years I drove 80,000 miles from Land’s End to John O’Groats, the Hebrides to Dover.I once drove a Triumph Dolomite Sprint from Carlisle to London in four hours. It was like dying and going to heaven.

Alas came speed cameras and too many cars. Recently a friend in Oxford was dinged for doing 32 in a 30 mph zone. More recently you can’t even bring a car in there. One Saturday on one of my last visits to Dorset, I had to use an Ordnance map and one-track lanes to get round the traffic in and out of Dorchester. I don’t drive there anymore.

2 thoughts on “Chequered Past: Of England and the Automobile”

Lovely piece, hank you. Please never give up on cars. “So it went with the British industry, whose approach to foreign markets was often myopic.” To “myopic” I would add “jingoistic, condescending and complacent.” If sometime you have time on your hands (!) might I suggest you search for which will take you to an opinion piece I wrote addressing that from the point of view of an ex-Brit service rep for the Canadian arm of a British car manufacturer (Rootes, actually) fighting uneven odds.

I believe I have a copy of ‘1957 Cars’, but can’t locate it… maybe they have all dissipated into the ether.

Ferrari: I’m still delighted about the original Ford GT40. I’ve owned two British cars; both Jaguars (Mark 9 and XJS). Both were low mileage, the XJS was owned and scrupulously maintained by the original owner, whom I knew.

Both were disappointments. I say “They don’t nickel and dime you in repairs, they hundred and thousand you.” The hapless Mark 9 was purloined out of my driveway one night, never to be seen again. I still have the pink slip after 40 years missing.

–

Thanks, Scott. For similar amusing Jaguar experiences, scroll to “O’Kane and the English” in my post: “Old Jags & Allards: The Whimsey and Fun of Dick O’Kane.” His experiences will be familiar to you. —RML

Comments are closed.