Cars & Churchill: Blood, Sweat & Gears (1) Mors the Pity

Having written about cars and Winston Churchill for fifty years, I finally produced a piece on them both. From exotica like Mors, Napier and Rolls-Royce to more prosaic makes like Austin, Humber and Wolseley, the story was three decades in coming. But I am satisfied that it is now complete.

Part 1:

Excerpt only. For footnotes, illustrations and a roster of cars, see The Automobile (UK), August 2016. A pdf of the article is available upon request: click here.

Mors the pity

Always fascinated by new technology, Winston Churchill welcomed the motorcar, buying his first in 1901 at the age of 26. It was French Mors—one of only two non-British cars Churchill would ever own—and a disappointment. He might have been thinking of it when during World War II he said of France: “The destiny of a great nation has never yet been settled by the temporary condition of its technical apparatus.”

Mors is Latin for death, and Emile Voilu, Churchill’s enthusiastic French chauffeur, appeared to take this seriously, sustaining many a bump. Churchill kept the Mors through 1906, but it lay unrepaired for long periods; this upset Voilu, who looked upon it as his personal equipage. In 1904 Churchill wrote: “The motor was a real sad business. Nearly £28 to put it straight after a fortnight’s utter neglect. The fury of the Frenchman at seeing its condition was disquieting to witness.”

Edging his bets

In 1911 the Churchills bought a new Napier 15hp landaulette from a great racing driver and Napier exponent S.F. Edge, “the ebullient Australian.” With extras the Napier cost over £600 (£54,000 today). Churchill specified buff cord upholstery and “Marlborough blue,” the house color of his famous ancestor, the First Duke of Marlborough. Edge didn’t know what shade of blue that was, and the car was delivered in red, but Edge promised a repaint when convenient—repaints were less complicated in those days. The Churchills were already on holiday in Scotland, so they hired a works engineer to drive to meet them, and to serve as chauffeur.

They visited the King at Balmoral and Prime Minister H.H. Asquith in East Lothian. There Asquith offered Churchill a coveted prize: the Admiralty. He took office in October, prepared the Fleet for battle, tried and failed to promote peace, and went to war full of fight in 1914. Ignominously sacked during the Dardanelles-Gallipoli debacle of May 1915, he spent six months in brooding impotence. Then he joined his regiment in Flanders, where (as he had written earlier) he was “shot at without result.”

Annus Horribilis

Nineteen twenty-one was a year of tragedy, with the deaths of Clementine’s brother, Winston’s mother, and Marigold, their 2 1/2-year-old daughter. The child died only days after they’d purchased the finest car they would ever own, a 1921 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost cabriolet by Barker. Marigold’s death on August 23rd—from septicemia, which modern antibiotics would easily vanquish—brought deep gloom.

Preoccupied with his personal loss, the Irish rebellion and troubles in Iraq, Churchill gave little thought to the car. When he returned to London in late September, the Silver Ghost only reminded him of their loss. In October, his Aunt Cornelia, Lady Wimborne, took the Rolls off his hands for only about £150 less than he had paid. Although he would frequently hire a 20/25 after World War II, Churchill never again owned a Rolls-Royce. He made do with government cars until 1923 when, having purchased a country estate, he went shopping for transport.

“Weighed and found wanting”

In late 1922 Churchill bought Chartwell, a spacious brick pile overlooking the Weald of Kent, where he would live until he died. His daughter Sarah recalled the day he bundled his children into “an old Wolseley” and drove them down to see it, overgrown with ivy and in need of major renovation:

We were all so excited when we set off for home that my father couldn’t make the car start. Help was solicited and an amazing number of people helped to push the Wolseley about a quarter of a mile along a slight incline so that we could have the benefit of the subsequent decline to start the reluctant engine. I noticed the people helping were very red in the face, but ours were redder still when it was discovered that the ignition was off and the brake on.

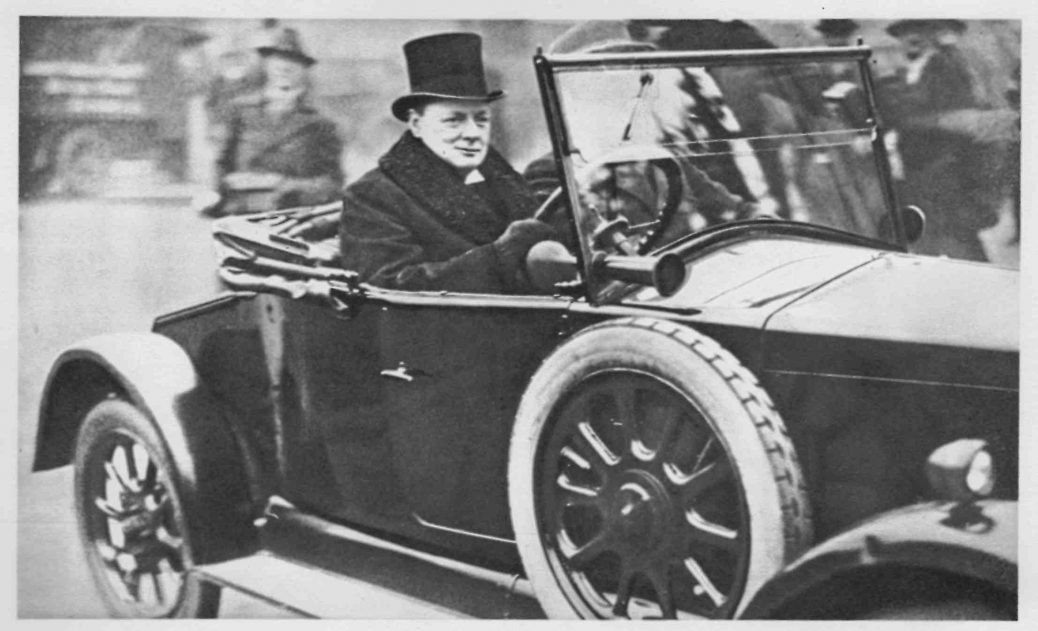

The “old Wolseley” was likely borrowed. It was 1923 before Churchill bought any cars: a Wolseley two seater and a four-seat tourer. He owned five Wolseleys, but was most often photographed in the “little car,” which looked like its springs and frame were held together with bailing wire, with a slight assist from the taillamp wires. It marked his transition to self-drive cars. In retrospect he might have considered that “an awful milestone in our history,” when “terrible words were pronounced” about his driving: “Thou art weighed in the balance and found wanting.”

Menace on the road

Behind the wheel, Churchill was scary. His bodyguard, the towering Inspector Walter Thompson, was sometimes photographed nervously sitting bolt upright next to him. “Mr. Churchill has an immense grasp of the advantages and uses of the machine age,” Thompson wrote. “…but he has no personal sensitivity about the machines themselves. He strips gears and rams head-on toward anything.” One Wolseley’s flywheel was missing so many teeth that if the engine stopped in the wrong position it had to be crank-started. They removed the front number plate to leave the crank in place, and were thus often stopped by the law. “Take a good look at this car,” Churchill lectured one policeman, “and never, never stop me again.”

Churchill became Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1925. A year later, after the General Strike had paralyzed Britain for ten days, the Duke of Westminster invited him to relax at his residence near Dieppe. Exhausted from the strike ordeal, Churchill opted to drive to the Channel ferry himself. That was a bad sign, Thompson said. “It either means that he is cross and subconsciously wants to smash up something, or that he is dangerously elated and things will get smashed up anyhow through careless exuberance.”

Jumping the queue

Off they went, flat-out. At Croydon, they encountered road repairs and a queue of cars. Suddenly, Thompson recalled, they were off the road, “progressing right down the sidewalk [pavement]. We got into a nice mess in no time and had to make an abrupt stop. (Churchill was unusually good in the technique of an abrupt stop.)”

Next, they were looking at “the face of an outraged local constable.”

“You fool!” the policeman shouted. Then he “swore most richly for some seconds.” Churchill’s head hung. “He did have the civic sense to say he was sorry,” Thompson continued. “…the matchless voice of the man identified him at once to the constable.” ‘Sorry, Mr. Churchill,’ the policeman apologised.

“Then the majesty of the constable’s office and the disgusting guilt of the violator brought forth, in gentle sarcasm, a caution that withered Churchill and kept him silent clear to the Channel. ‘Do try to stay in the road, sir.’”

By the late 1920s, no doubt to the relief of drivers on the London-Westerham road, Churchill had quit driving. But he often rode “up front” with his new chauffeur, Sam Howes. One foggy night in the Wolseley tourer, they could not read a road sign. Churchill stooped, “made a back,” and told Howes to climb on to read the directions. Howes was sure few “gentlemen on his level would have bent down for me to stand on their back.” Continued in Part 2….

15 thoughts on “Cars & Churchill: Blood, Sweat & Gears (1) Mors the Pity”

I have heard that Winston Churchill had a righthand drive Packard but have been unable to substantiate this claim, If anyone has any information please let me know. Many thanks in advance.

–

Sorry, no, his only American vehicle was a Jeep used around Chartwell Farm just after the war.Though he was chauffered in Packards from time to time. Click here and scroll down.

—RML

Excellent summary of his cars and encounters topped by him sitting in the Wolseley 10 .Well done

I recently heard of a Russian oligarch having an MG that belonged to Churchill . He has hidden it away with other classics . The house keeper is selling off his furniture I may buy a table and hope to find out more .

–

Nothing like fooling a Russian oligarch, Simon! No MGs on the roster. RML

If your uncle pinched Churchill’s car in 1919, it would have been a Rolls-Royce loaned to him by his friend the Duke of Westminster. It might well have been black. (In my original article for The Automobile I wrote: “His Napier was sold by 1917, when Churchill returned to Whitehall as Minister of Munitions. He went on to the War Office and Air Ministry (1919-21) and the Colonial Office (1921-22). He mainly used government cars—and, through mid-1919, a Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost loaned by his friend “Bendor,” the Duke of Westminster. He considered buying a used Charron landaulette, but experience prevailed and he avoided another French adventure.”)

[See Mr Cornes’s previous comment below.] The only sources for my uncle stealing the car in February / March 1919 are the newspaper archives, in which the newspaper says it was painted black.

I know the claims about the SS Jaguar. A claim was also made that Chartwell offered $1m for the car, but Chartwell has no record of this. Several of us went round and round on the story, but in the end were never able to find any documentary evidence that Churchill ever owned one, much less that the King gave one to him, which seems improbable. (King George V died around the time the SS was coming out, and if George VI ever gave him one, it is not documented in the Churchill or other archives.) Randolph Churchill owned a Jaguar, maybe Sarah Churchill did too, but that’s as close as their father ever got to the marque.

The SS Jaguar according to the owner was given to Churchill by the King; he gave it to Sarah. It was in the States. I also found an Austin of his. The owner of the Rolls had no idea it had belonged to Churchill. I saw a newspaper or book which referenced the Mercedes duplex. You will know the Land Rover was refurbished and is in a museum in Switzerland. It was at Goodwood a few years ago

The Jaguar apparently belonged to the King, who gave it to Churchill who then passed onto Sarah. It is in the states. The owners of the Rolls had no idea 60AE had belonged to Churchill. I also tracked down one of his Austins. You will probably know his Land Rover is restored and in a museum in Switzerland. Did you ever come across the Charron he put a deposit on.

I’d be interested in any provenance you found on the SS Jaguar. There is one claimed by its owner to have been Churchill’s, but the only SS Jaguar I could track belonged to his son Randolph. Also, the Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost was owned only briefly, and sold in 1921, before he had acquired Chartwell. Historians suggest it reminded him too much of the loss of his 2 1/2-year-old daughter Marigold, and he couldn’t bear to keep it.

When I worked at Chartwell I researched Churchill cars, and found some of the original cars that he brought to Chartwell: his Roller, Hillman Husky, Land Rover. I also discovered his SS Jaguar.

I can find no trace of it.

Did Churchill owned a 1935 Austin 6/18 Chalfont a 7 seater it was later in 1944 had a taxi license to send children from London to Scotland to get out of the bombing It was refurbished in 1968 and put in a museum

That’s an interesting connection! Churchill was between cars in 1919, having sold his Napier in 1916. Until 1921, when he bought a Rolls of his own, he borrowed a Silver Ghost from his friend “Bendor,” the Duke of Westminster. That must have been the one your uncle pinched. Clearly he had good taste.

What was Winston Churchill’s car in 1919 (March) my uncle, was imprisoned in HMP Wandsworth for 12 months for stealing it, whilst working on it, at Grove Park Garage.

Nothing in the Archives on a Mercedes (or a Benz, which one source states he owned). It turned out to be a garage that specialized in Benzes which did some work on his Mors. Do you have any references?

What about his Mercedes duplex?

Comments are closed.