All the Luck: Howard A. “Dutch” Darrin, Part 1

Dutch Darrin was supremely lucky—and one of the most charming things about him was that he never ceased saying so.

Dutch Darrin was supremely lucky—and one of the most charming things about him was that he never ceased saying so.

Part 1

Excerpt only. For full text and illustrations and a roster of Packard Darrins, see The Automobile, May 2017.

Looking back on the previous century, the historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. reflected that individuals do make a difference: “In December 1931 Churchill, crossing Fifth Avenue in New York City, looked in the wrong direction and was knocked down by an automobile. Fourteen months later Franklin Roosevelt was fired on by an assassin….Would the next two decades have been the same had the car killed Churchill in 1931 and the bullet killed Roosevelt in 1933?”

Automotive history is replete with reminders of Schlesinger’s axiom. It is certain, for example, that the history of Packard would have been less glorious without the Darrin Packards. Were it not for Dutch Darrin’s garrulous, quarrelsome, self-promoting persistence with a conservative management, they would not exist. I do not of course compare him with global figures like Churchill—but the auto world without him would be a poorer place.

“A Little Dutchman”

Born in Cranford, New Jersey in 1897, Dutch (nicknamed when his father said he looked “like a little Dutchman”) manifested an early interest in motorized transport—newer then than the Internet is today. A friend of his father’s founded Automobile Topics, and took him on a ten-year-old dogsbody; young Howard pursued technical training and joined Westinghouse, who also happened to be working for John North Willys, America’s number two car producer.

Willys, Dutch learned, was looking for an automatic gearshift—the very thing for car buyers going horseless for the first time. Dutch so persuaded Mr. Willys that he could build one that he sent him a car. Realizing he knew “nothing whatsoever about building an electric gearshift,” he eyeballed the transmission, and cobbled together two small electric motors activated by buttons on the steering column. The gadget actually worked. Willys hoped to mass-produce it in 1917, but tabled it when production was cut as America entered the Great War. “Disaster is my business,” Dutch quipped later. In fact, luck was with him: much greater things lay in store.

In early 1918 Darrin joined the U.S. Air Service, flying combat missions over France, part of a force that shot down 756 enemy aircraft. Discharged, he returned to New Jersey and founded Aero Limited, America’s first scheduled airline. Connecting Atlantic City with Florida and Nassau, he used a fleet of converted army-surplus flying boats. Then he purchased a pair of Delage chassis and built his first custom bodies, selling one to singer Al Jolson. That, he decided, was more fun and more profitable than the airline business—and gave him more time to play polo, which he loved. Luckily he met Tom Hibbard, founder of LeBaron, the distinguished coachbuilder whose bodies graced the finest marques of Europe and America.

Hibbard & Darrin

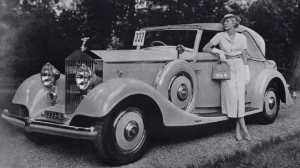

Phantom I is a fine example of early Hibbard

& Darrin coachwork. (The Automobile)

Both Francophiles, Darrin and Hibbard wished to seek their fortunes in Paris, a city attempting to reestablish the Belle Époque after five years of World War I. Dutch wanted to open a Minerva dealership, using its chassis to mount custom bodies for visiting Americans. Minerva was selling only a handful of cars in France, but the young entrepreneurs convinced the Belgian company that their plan would work. In 1922 they founded Hibbard & Darrin coachworks. Renting a showroom, they decorated it with fine paintings and tapestries, borrowed from Paris antique dealers with the promise of publicity. At the age of 25, Dutch was a coachbuilder—more or less.

“Believe me, we weren’t geniuses,” Darrin said. “We thought ideas should be young, and old customs disregarded.” H&D minimized structural wood, which they considered old-fashioned. In 1929 they introduced a new aluminium alloy, Alpax, from which they made thin, light aluminum body sheeting called Stylentlyte, to enable more elaborate and rakish body styling. Hibbard and Darrin soon consulted for the world’s top manufacturers: GM’s Al Sloan, Stutz’s Fred Moscovics, Louis Renault, Sir Henry Royce, André Citröen, Sir John Siddeley.

In Paris Dutch made contacts with key Americans, friends he would rely on later. When Edsel Ford dropped by to order six custom Lincolns, Darrin harangued him about redesigning the Model T. Affronted, Edsel insisted the Tin Lizzy would never change. Two years later, after Ford had lost millions stopping “T” production while tooling up for the Model A, Edsel said, “Dutch, why didn’t you hit me over the head with your polo mallet?”

Fernandez & Darrin

Tom Hibbard was also making friends, and because of Dutch’s colourful salesmanship, Detroit moguls tended to regard Tom as the designer of the duo. In late 1931, the Depression cut into the custom body business. Hibbard returned home to work for General Motors. Dutch stuck it out, teaming with the banker J. Fernandez, who offered him a modern factory and a beautiful showroom on the Champs Elysées. Lacking funds, Hibbard & Darrin had always made their clients supply their own chassis; Fernandez enabled Darrin to buy chassis outright. Dutch also continued to consult with volume manufacturers. For André Citroen in 1932, he built a prototype for the 1934 Traction Avant, first car with a mass-produced unit body.

continued in Part 2…