Confessions of a Rootes Autoholic

Remarks prepared for a national meeting of Tigers East/Alpines East, which circumstances prevented me from attending. The text includes remarks about the Sunbeam Harrington Le Mans, which are posted separately.

“You wouldn’t believe how slow my Sunbeams were”

It sounds blasphemous, but I’ve never been able to relate to Ferraris, possibly because I could never afford one. Give me a quirky English rig with an interesting past and a shape you don’t see every day. There’s something about leather and walnut, the way the rain beads on the bonnet…. It reminds you of the time when almost everybody in Britain could build a sports car, and many did. As an old Triumph worker said when the last TR6 left the line: “It rides hard and smells of oil. They just don’t make cars like that anymore.”

Sunbeam-Talbot had a good competition pedigree before the Second World War. But in 1935 the firm was bought by the Rootes Group, William and his brother Reginald. They were interested in production not competition, so not much happened for awhile.

Enthusiasm revived when a successful rally driver, Norman Garrad, joined the company as competitions manager. After the war, Rootes launched a two-liter sports saloon, the Sunbeam-Talbot 90. Norman thought he could make it into a rally winner.

Driving a 90 in 1952, Stirling Moss won fifty pounds by finishing second behind Sidney Allard in the punishing Monte Carlo Rally. This convinced Norman that Rootes might have a competitive car after all. Moss wasn’t sure. “You wouldn’t believe how slow my Sunbeams were,” Sir Stirling later told my friend, the late motoring writer Graham Robson. Graham replied: “Yes I would!”

Finding your Rootes

Reginald and Billy Rootes were empire builders who envisioned a kind of mini-General Motors. By the late Forties they controlled four old-line companaies: Hillman, Humber, Singer and Sunbeam-Talbot. I’ve owned six of their cars, at least one of each make except for Singer. I am a certified “Rootes-oholic.” Or maybe just certifiable.

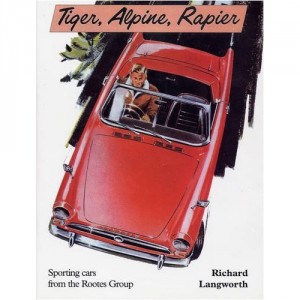

For three years running, teams of Sunbeams appeared at the great French endurance race, the Twenty-four Hours of Le Mans. You can read about them in my book, Tiger Alpine Rapier: Sporting Cars from the Rootes Group. But don’t pay the silly prices quoted on Amazon. Use Bookfinder.com to find a cheaper copy.

My first Rootes product was a powder blue 1962 Sunbeam Alpine Series 2, which I bought new and ran the wheels off, including a memorable twelve-hour overnight rally in Fairfield County, Connecticut. It replaced a Triumph TR3, and getting back into a car with roll-up windows and a top you could put up without a tool kit was true luxury.

Hilda, the friendly Hillman

Years later came Hilda, a 1960 Minx convertible. Remember the three position top with the intermediate “landau” position? Hilda was a lovely low-mileage car without any rust.

She had one peculiar and quaintly English trait. Whenever you drove through a puddle deeper than two inches, she just stopped. The drill was to get out, remove the distributor cap, dry the insides out with a rag, and voilà—she was off and running again.

My fondest memory of Hilda was driving flat out at the Bridgehampton, Long Island road course. Hilda was so slow you could drive the whole track, hairpins and all, with your foot flat on the floor and never come to grief. This proved to be a good thing. Far behind a TR5 down the straightaway, I easily dodged its flying bonnet when it came unstuck. It flew past like an errant bat or a stealth bomber. It is a wonder we all didn’t go to jail that day.

There’s safety in Humbers

Not many Rootes collectors care about Humbers, but they might be missing something. My 1967 Imperial—last year for the big luxury Humbers—was one of the nicest cars I’ve owned, with its smooth and quiet 3-liter six, swathed with Connolly hides, wool and walnut. It was the top of the line, with a body by Thrupp and Maberly in London. Rootes bought that coachbuilding company to handle the final finish on its luxury cars.

Never mind the broad chromium smile and the chunky lines. The Imperial was as quiet as a bank vault—a wonderful road car and a good handler despite its bulk. It was a Series 5, with the squared-off roofline and large glass area. I gave it up after a few years of hunting for spare parts. The supply in the USA is not large, and was twice laid up for months for lack of a crucial part.

Humber rated a chapter in my sporting Rootes book. The motoring writer Michael Sedgwick, our beloved “Sedgewarbler,” said: “Langworth is going way over the top with that one. All I can remember about Humbers is that they gave me a bad case of mal de mer every time I drove one.” Oh well!

Few realize this, but the oddly named Super Snipe (down-market from the Imperial) actually competed with distinction. In the 1950 Monte Carlo Rally, Norman Garrad fitted out a Mark II for the Dutch drivers Maurice Gatsonides and K.S. Barendeg, who finished second in class. Snipes also finished near the top of their class in the 1962-63 East African and RAC Rallies.

Meet the Tiger

But this is the 60th Anniversary of the Rootes Sunbeam Tiger, so let’s get on to most exciting car Billy and Reg built. I am one of the diminishing few who set out to drive one the moment it was announced—and bought one new a few months later.

“The original Sunbeam Tiger,” wrote Mike Bumbeck in Hemmings Classic Car, “was a beastly V-12 built in 1926 for setting land speed records at the hands of Major H.O.D Segrave. The mighty Tiger was later configured to run flat out around the Brooklands high-banked track. This altogether determined race car could hardly be thought of as light, agile, or friendly. The next Sunbeam Tiger, named after the original, was a different car in every way.”

“The original Sunbeam Tiger,” wrote Mike Bumbeck in Hemmings Classic Car, “was a beastly V-12 built in 1926 for setting land speed records at the hands of Major H.O.D Segrave. The mighty Tiger was later configured to run flat out around the Brooklands high-banked track. This altogether determined race car could hardly be thought of as light, agile, or friendly. The next Sunbeam Tiger, named after the original, was a different car in every way.”

I vividly remember my first encounter with the Tiger sixty years ago. I was a penurious two-striper in the U.S. Coast Guard. I had no right even to think I could afford one.

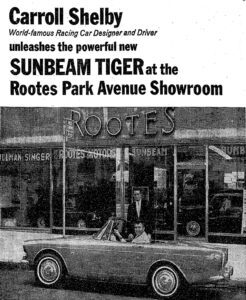

But I’d owned an Alpine, and the idea of an Alpine with that sweet little Ford V-8, conjured up by the great Carroll Shelby, was exciting. So I toddled off to the Rootes showroom on Park Avenue in Manhattan to see what this new car was about and maybe talk them into letting me drive one.

The demo was black, with a tan mock-pigskin interior. The first thing I saw was the walnut instrument panel—so different from that nondescript grey dash on my old Alpine. I climbed in and noticed the second thing: a 140 mph speedometer.

“I’ve got to get one!”

Remember, I’d been driving an Alpine, so the rest of this car seemed more or less familiar. But not the driving!

The plate glass windows of the Rootes showroom retracted into the street, so you could literally drive a car off the floor. They rolled one down and I exited onto Park Avenue. Gingerly, I worked my way to the waterfront, got onto the East Side Drive and put my foot down. Lightning struck! I had one thought: I’ve got to get one of these!

On September 14th, 1965, I bought B9471128. (Does that make it the 128th built? I’m not sure.) It was Midnight blue, with a factory hardtop painted to match, and one of the better-grained walnut dashboards (they varied).

It cost $3902, a king’s ransom. Still, that was only $100 more than the noisy, hard-riding, vastly overrated Austin-Healey 3000, $1700 less than a Jaguar E-type, $2000 less than Shelby’s already legendary Cobra.

I put 25,000 miles on it before trading it in on an air conditioned VW Karmann Ghia two years later. Yes, I know—foolishness! But at the time it made sense, with the long, hot business trips I was then obliged to endure. (The Ghia was like my Hillman. You could drive it all day with your foot to the floor and never be arrested.)

With its effortless performance, that Tiger was the most soul-satisfying two-seater I ever owned. It was also one of the cars I should never have sold—as it kept reminding me by reappearing!

The cat came back

Then, back came my Mark I to haunt me—twice. The first was a night in 1969, outside Lancaster, Pennsylvania, when I spotted it under the floodlights at a used car dealership. I pulled over and looked inside. Sure enough, there was the burn mark I’d made with my pipe next to the console ashtray. Incidentally, the odometer now showed 5000 fewer miles than it had when we traded it in.

Recalling what fun that car had been, I was so excited that I forgot the speed limit and was immediately ticketed by a state trooper. Through a mutual friend in the car business, I tried to buy it back at a trade discount, but the dealer wouldn’t budge.

Then in 2017, there it was again, advertised in Hemmings, by the same owner since 1984! The value had increased somewhat, however…

By that time I’d already acquired another Tiger, but #1128 seemed to have aged well: still with the smooth dark blue paint job, still with the hardtop. The soft top had been replaced with a light blue non-stock top, the front bumper guards were missing and the wheels were changed, But all in all it still looked good. I hope it is happy and healthy, wherever it is. If anybody knows how to track it, I’d sure like to know.

Why the Tiger failed

How could so fine a sports car fail? That is a short, sad story. The Tiger was never a hot seller. I’ve talked to dealers who were flogging leftovers at cost in order to get rid of them by 1966. Had things been otherwise, the wealthy corporation that was Chrysler—which acquired Rootes in 1965—would have kept it in production.

In Rootes showrooms, the Tiger was an anomaly compared to the Hillmans (should I say Hillmen?), Singers and Humbers. It also looked too much like the cheaper, slower Alpine. Unique styling is vital in a car like this. And the competition was tough. In 1965 you could buy a flashy Corvette Sting Ray for as little as $300 more than a Tiger, and 24,000 Americans did. The Tiger lacked that essential visibility which made the String Ray and E-type successful in the vital American market.

What all this led to is well known. After a half-heated attempt to stuff in a Valiant V8, to avoid selling a Chrysler product with a Ford engine, Chrysler simply dumped the Tiger. Pay no attention to the intriguing, well-known photos of “future” designs. They are trifles light as air. No Chrysler executive ever came close to commissioning a prototype. Only about 7000 were built between 1964 and 1967. The Tiger expired because it didn’t sell.

One more for the road

In 2013, I found another Tiger: a red 1966 Mark Ia. It had a straight, rust-free body and a flawless “resale red” paint job, but needed lots of mechanical work, new wheels and a new dash. I hung in there with it for eight years, an expensive restoration. It lives now in Massachusetts, with a collector of V-8 sports cars.

Somehow, I never warmed to it as I did to our original Mark I. Chrysler was building them by now, and engaged in a certain amount of cheapening. The slick metal covers that so neatly hid the Mark I convertible top were replaced by a vinyl boot. The Sunbeam letters were shaved from the nose. The cowl showed seams and square bonnet corners where the Mark Is had rounded corners and seamless joints. Memories of our Mark I were still too strong, I guess.

Still, six Rootes cars over a lifetime isn’t a bad testimony. That’s at least three more than Winston Churchill owned, and he liked them fine. So did I.

Further reading

“Harrington Le Mans: Sunbeam’s Lovely Gran Turismo,” 2020.

“Cars & Churchill: Blood, Sweat and Gears, Part 3, Humber,” 2023.

“Chequered Past: Of England and the Automobile,” 2023.