“The World’s Great Stories” Retold by Winston Churchill

Excerpted from “Winston Churchill Retells the World’s Great Stories,” written for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original text in three parts with more links and images starting with Part 1, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, fill in your email in the box entitled “Stay in touch with us.” Your email address always remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Greats by a Great

How would you like to read great novels in the words of Winston Churchill? Such a collection exists. In 1933, Churchill retold a dozen of “The World’s Great Stories” for The News of the World. Six also appeared in the Chicago Sunday Tribune. Five were reprinted in 1941. Then they were forgotten, lost among his “potboilers” of the 1930s. In 1975 they were briefly resurrected in the limited edition Collected Essays of Sir Winston Churchill. The publishing history is entry C393 in Ronald Cohen’s masterful Bibliography.

Why would Churchill wish to retell such classics as Uncle Tom’s Cabin, The Count of Monte Cristo, Don Quixote, or A Tale of Two Cities? Because he was paid well to do so! Never independently wealthy, he worked hard to maintain his luxurious lifestyle—and the heavy entertainment and travel overhead of an active political career. “I earned my livelihood by dictating articles which had a wide circulation not only in Great Britain and the United States,” he wrote, “but also, before Hitler’s shadow fell upon them, in the most famous newspapers of sixteen European countries. I lived in fact from mouth to hand.”

His 1930s articles ranged from the esoteric (“Are There Men on the Moon?”) to the whimsical (“Are We Too Clever?”) to the historical (“Moses”). Interspersed were thoughtful reflections on civilization (“Mass Effects in Modern Life”) or international developments (“How Germany is Arming”). Somewhat dismissively, Churchill and his staff called some of these “potboilers.” “Very exciting,” remembered his secretary Grace Hamblin: “They were quickly put out and sent off usually the next day. He got his money very quickly, which he liked too. We all liked doing potboilers.”

Genesis of the “Great Stories”

Churchill rarely had to “shop” his material—publishers came to him. In mid-1932 it was newspaper baron Lord Riddell, who wrote:

Would it appeal to you to write six articles “Six Great Stories of the World Retold by Winston Churchill”? Sensational things like Monte Cristo, Wilkie Collins’ Moonstone, Rider Haggard’s She, Ben-Hur, Anatole France’s Thais, Uncle Tom’s Cabin—5000 words each article. What would you want for them to be published in the News of the World. You would have an enormous audience—3,500,000 per week.”

Churchill replied by return, acclaiming Riddell’s “brilliant idea.” Not omitting to note that Collier’s were paying him $1500 (£312) an article, he offered Riddell six stories for £2000. He then hired his onetime private secretary and literary collaborator Eddie Marsh to help write drafts at £25 each—a modest overhead! “If I had read about 2500 words of your ideas on each of the selected books,” he wrote Marsh, “it would be a foundation on which I could tell my story. I shall of course be reading them all again myself.”

“The art of the deal”

Good salesman that he was, Churchill then interested Robert McCormick’s Chicago Tribune in the American rights for £1800. His combined fee was £3800 ($18,000, or $380,000 in today’s money). The Tribune could not start until January 1933 but Riddell was ready to go. Churchill had a problem, since he’d promised McCormick simultaneous release. “[I]t never occurred to me till you said so the other night that you would want to publish them till after the end of the year,” he wrote Riddell. “I hope therefore that you will not mind waiting till January 8, or at your convenience later in the month.”

Riddell was so pleased with the first four stories that he asked for more. “Good news,” WSC wrote Marsh in December. “They like them so much that they have ordered another half dozen.” Riddell suggested some titles, but left the choices to Churchill. (McCormick settled for the original six, although he replaced Ben-Hur with Jane Eyre from the second set).

“Rot, padding, feuilleton and pemmicanisation”

Retelling whole novels in 5000 words each posed a major task of condensation. Marsh submitted a summary of The Count of Monte Cristo. No good, Churchill replied: “[W]e are not writing great stories summarised, but great stories retold. It is essential to select the salient features of the tale and make them live in all their fullness, leaving the rest in darkness. In Monte Cristo I shall give 1000 words to the plot against Dantes and 2500 to the terrific prison drama and 1500 to the revenge. That pretty well fixes the dimensions.” Anyone who has read Monte Cristo will appreciate that Churchill had his emphasis right.

Along with Dumas they liked Dickens, but Churchill knew he’d have to jettison vast verbiage. This gave him opportunity to exercise his vocabulary: “Both Dickens and Dumas mixed up a lot of rot and padding in their writing for feuilleton purposes,” he told Marsh, “all of which goes overboard through my lee scuppers.” He knew A Tale of Two Cities well, “though I suppose I shall have to re-read it. It certainly lends itself to dramatic pemmicanisation.”

This tells us much about Churchill’s command of the assignment and direction of the writing. Eddie Marsh, a brilliant polymath, was the perfect foil and draft writer. As the work continued, Marsh wrote an increasing portion of the drafts, especially after the first six. Nevertheless, Churchill finalized them. His special take on each novel is what interests today’s readers.

The first six

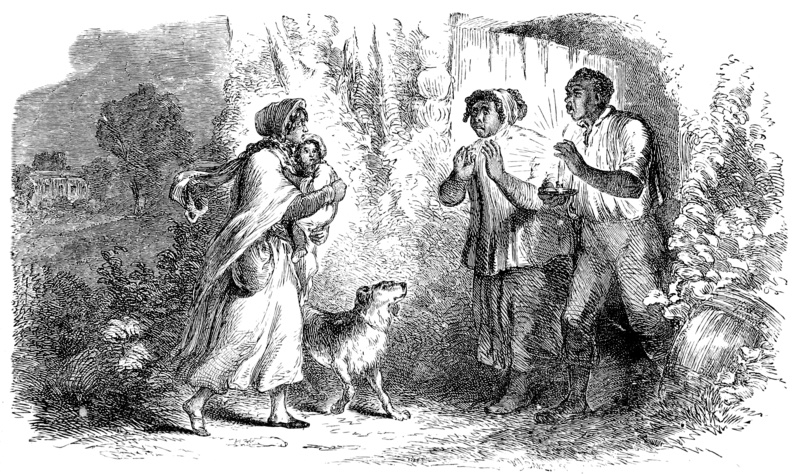

- Uncle Tom’s Cabin, by Harriet Beecher Stowe

- The Count of Monte Cristo, by Alexandre Dumas

- The Moonstone, by Wilkie Collins

- Ben-Hur, by Lewis Wallace*

- Tess of the D’Urbervilles, by Thomas Hardy

- A Tale of Two Cities, by Charles Dickens

* The Chicago Sunday Tribune substituted Jane Eyre.

** Save for The Moonstone, these stories were reprinted in the Sunday Dispatch in 1941. For books or e-books, enter titles in Amazon.com or Bookfinder.com.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin and The Count of Monte Cristo were the first choices. Churchill rejected She—“a slight work though very exciting. I think that King Solomon’s Mines is the best of Rider Haggard’s books.” He thought Shakespeare’s and Goethe’s works “too great to be dealt with in this way, except Faust, which can always be told.” He considered A Tale of Two Cities, Ivanhoe, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Treasure Island, Ten Thousand a Year, Robbery Under Arms and Faust.

Ultimately the last four were dropped, while Ivanhoe made the second cut. Lawyers consulted copyright holders, who were mostly fine with what they saw as welcome publicity. Only Harper & Brothers, publishers of Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper, withheld permission.

Omissions and an addition

Churchill decided against Anatole France’s Thais, and Marsh agreed: “[I]t would be difficult to do justice to the diseased, suppressed sexuality (of which it is so terrible a story) in the course of a 5000-word article….. [It is] much better done at length in French, than in abrupt and abridged English.” From Chicago, Robert McCormick suggested Wuthering Heights, but they’d already settled on Brontë’s Jane Eyre. McCormick mentioned Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, but Churchill hadn’t read that mammoth tome, and Riddell didn’t want it.

Nor had Churchill read Ben-Hur, which he considered “mere popular sentiment.” But Lord Riddell liked it, so Eddie Marsh tackled a draft. “Golly what a book!” Marsh wrote. “The seafight is really fun, so I’m making that a ‘high-light,’ and there will be another in the chariot-race; but there are terrible unmanageable tracts between—I don’t think I’ve ever read a book in such bad English.” In the final version, Churchill gave a beautiful flourish to Biblical story of the Wise Men at the birth of Jesus.

The second cut

- Jane Eyre, by Charlotte Brontë*

- Adam Bede, by George Eliot

- Vice Versa, by Thomas Anstey Guthrie

- Ivanhoe, by Walter Scott

- Westward Ho!, by Charles Kingsley

- Don Quixote, by Miguel de Cervantes

*Substituted for Ben-Hur in the Chicago Sunday Tribune.

When Riddell asked for more titles, Churchill sent further ideas to Marsh for comment. Both agreed on Jane Eyre, Adam Bede, Westward Ho!, Ivanhoe and Vice Versa. The Cloister and the Hearth, The Wandering Jew, East Lynne, Vanity Fair and The Last Days of Pompeii were rejected. Riddell was still pushing Faust, and Churchill thought “the full German story would be magnificent,” but it proved too unwieldy for a 5000-word retelling. He also wondered whether Vice Versa “was not below the middle-class level which goes to these schools.” Marsh thought Vice Versa—a light Victorian novel—a break from the other, mostly gloomy stories.

Instead of Goethe, Riddell got Cervantes. “His Lordship thinks that Don Quixote would be a good thing,” wrote Violet Pearman, Churchill’s secretary, “although you find it rather heavy and with not much plot.” Riddell had learned of an upcoming film adaptation starring George Robey. “This should inspire you,” WSC informed Marsh. The film debuted in May, and Riddell saw to it that Churchill’s version appeared in March. It was the last in the series.

What makes these stories unique is, of course, Churchill’s vast background and experience. His telling adds poignant reflections and Churchillian phrases to the famous novels.

Links: Churchill’s stories one by one

For accounts and excerpts from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, The Count of Monte Cristo, The Moonstone and Ben-Hur, click here.

For Tess of the D’Urbervilles, A Tale of Two Cities, Jane Eyre, Adam Bede, Vice Versa, Ivanhoe, Westward Ho! and Don Quixote, click here.