Poy (Percy Fearon): The Classic Churchill Cartoonist

Excerpted from “Churchill by Poy: Cartoonist of a Vanished Age,” for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the unabridged text with endnotes and more illustrations, please click here.

“Fieldfare’s” Poy (Percy Fearon)

An enquiry from cartoon historian Tim Benson sent us to the library for Poy’s Churchill, by “Fieldfare” (1954). Tim runs the Political Cartoon Gallery, which exhibits and trades in original drawings. Many are from the great blossoming of British cartoons in the first half of the 20th century.

Among the most prominent was “Poy” (Percy Hutton Fearon, 1874-1948), who grew up on Staten Island, New York. His pseudonym derived from the American pronunciation of his first name (“Poycee”), which he abbreviated “Poy.” In Britain he joined London’s Evening News in 1913. He also worked for the Daily Mail. Poy created over 10,000 cartoons in 34 years. He was retired when war came in 1939—regretting that he could not contribute to wartime cartooning.

To mark Churchill’s 80th birthday in 1954, Percy Fearon’s nephew Henry published Poy’s Churchill in tribute to them both. Henry was also an Evening News hand, famous for his column on country walks, published under the pseudonym “Fieldfare.” His booklet is an eloquent charmer, featuring 50 of his uncle’s best cartoons.

Poy’s Churchill

“In this little book two great men are brought together,” writes “Fieldfare”: “In a sense, Poy is Churchill’s earliest and most constant biographer, and it is through his clear, cool, twinkling eyes that we watch here the long and active life of his subject.”

Fieldfare begins with the reign of King Edward VII (1901-10). No monarchy since the Norman Conquest, he wrote, compared with it. Fieldfare acknowledges the appalling poverty, crime, squalor and disease that also accompanied those years. Nevertheless, he sees “something of its magic,” and “the never equaled figures which it magically produced in every sphere of life, especially in politics.”

There is much of Churchill in those words, for the Edwardian era had scarcely ended when the First World War changed everything. Joining the Cabinet at age 34, Churchill commanded attention. He was, of course, a Victorian (born the same year as Poy). But “Thank God, every vestige of Victorianism was washed away in the ice-cool shining waters of Edwardian England.” Poy interpreted Churchill’s political life, his triumphs and foibles, from the catastrophe of one world war almost to the start of another.

“A modern Aesop”

Poy had no swords to rattle, no power of invective, no command of oratory; his weapon was a simple one of ridicule, and he could wield it with unerring skill…. Caricature was the object of all Poy’s work, but he never dipped his pen in vitriol…. He was not unlike a modern Aesop who…drew the simple truth with devastating clearness. Looking at any of his pictures you laugh because of their very rightness. It is only afterwards that you realise the brilliance of the drawing, and are staggered by the genius that created it.

Fieldfare says Poy led cartoonists away from “cruel lampoons” to “sane commentary….

This did not mean that he lost anything of the robustness of satire…but simply that he never made a single enemy. On the contrary, was loved by all who knew him. He could bring home his point, administer his rebuke, without ever resorting to personalities. Poy never lampooned physical defects:

Through Poy’s eyes we look upon [Churchill’s] whole career, all the vagaries and uncertainness of politics, until at last he becomes Prime Minister…. Alas for all of us, Poy retired in 1938 and was, therefore, unable to round off his history… showing the greatest statesman of the age at the zenith.

“Destiny took her time in claiming him…”

According to his nephew, Poy initially pictured young Winston as a chap thoroughly pleased with himself:

He is neatly, if carelessly, dressed [and] carries himself with a slight stoop, holding the lapels of his coat in the correct politician’s manner. He is not a little proud of the reddish curl on his head, and he is inclined to speak down to his audience…. Soon we see a subtle change: the plums of office are waiting to be plucked!…. Poy looks on amused at all the political jockeying and reduces it to terms which we can all understand.

At the Admiralty, Churchill moved from domestic to international affairs and, in time, the First World War. Poy now showed him as “a Man of Destiny, yet a man of excellent good humour withal.” Destiny took her time in claiming him, Fieldfare writes, but that wasn’t Poy’s fault.

Poy may have been the first cartoonist to make fun of Churchill’s tiny hats. Churchill claimed this started in 1910, when he donned a felt cap several sizes too small, and photos were taken. (See Gary Stiles, “Churchill in “Punch.”)

Poy himself denied this: “I had noticed the smallness of his hats long before 1910, but at that time the salient feature of my caricatures was the curl on the top of his head. It was only when this vanished prematurely that I turned to the hat, and made it the new hallmark.”

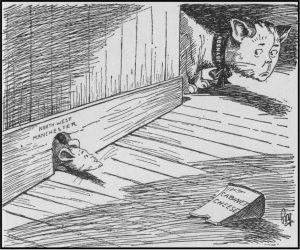

1921: “He who laughs lasts”

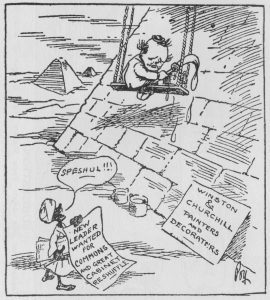

In early 1921, Churchill left for the Middle East Conference at Cairo amidst “halcyon calm” in Parliament. No sooner had was he gone than there came an upheaval. The ailing Andrew Bonar Law resigned as Leader of the House of Commons, an inviting position. To the amusement of political London, Poy lampooned Churchill for missing all the fun. Churchill wrote:

I had taken my paint-box to Cairo, and while the Conference was working under my guidance I made some lovely pictures of the Pyramids. Of course, I was neglected in all the rearrangements which took place in London. Lord Northcliffe was delighted with this cartoon. He sent me the original. He was particularly pleased with the little Arab news-vendor…roared with merriment as he pointed its beauties out to me. I accepted the gift with a stock grin. Of course, it was only a joke, but there was quite enough truth in it for it to be more funny to others than to oneself!

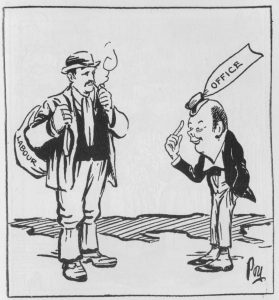

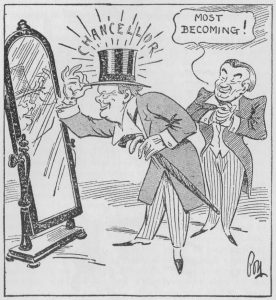

In 1924, to Churchill’s delighted surprise, newly elected Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin asked him to become Chancellor of the Exchequer. It was an exalted position, one his father had once held. “Poy,” wrote Fieldfare, “now showed him putting on a hat which really fitted him!”

Poy at his best

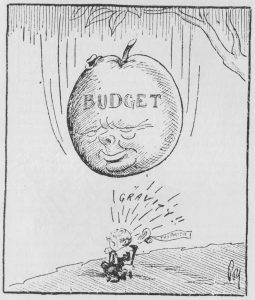

In early 1927, Chancellor Churchill was preparing his third budget for delivery to the House of Commons in April. March 19th presented Poy with a rare opportunity. It happened to coincide with the bicentenary of Isaac Newton. Here was a chance for Poy to apply what his nephew called his “topical flair”….

On the very eve of the anniversary, his cartoon showed us a wondering John Citizen, sitting beneath the famous apple tree, while an enormous “Budget” apple in the shape of Winston’s head is about to fall heavily upon him! By any measure, and at any time, this would be an outstandingly brilliant cartoon, but here its topicality lifted it into the spheres of immortality.

“The real apotheosis”

The general election of 1929 ended Baldwin’s first government and Churchill’s tenure at the Treasury. He would now spend a decade out of office, with accompanying loss of cartoonist attention. And he missed it:

Just as eels are supposed to get used to skinning, so politicians get used to being caricatured. In fact, by a strange trait in human nature, they even get to like it. If we must confess it, they are quite offended and downcast when the cartoons stop. They wonder what has gone wrong, they wonder what they have done amiss, [fearing] old age and obsolescence are creeping upon them. They murmur: “We are not mauled and maltreated as we used to be. The great days are ended.”

Of course as we know, the great days were yet to come. Poy had drawn “The Apotheosis of Winston” in 1911, his nephew wrote, “but he lived to see the real apotheosis in the terrible days of the Hitler conflict.” And there was that final drawing, “Accent on the WIN,” which summed up the story.

Hail and farewell

Today, when even Churchill’s minor gaffes are magnified out of proportion by the ill-read and the ignorant, his reputation broadly survives. Fieldfare’s eloquent conclusion to Poy’s Churchill is therefore worth repeating:

The petty jealousies which had clouded the early years, the political squabbles, the many mistakes and misunderstandings of a long life in the House of Commons are all forgotten now by the ordinary man in the street—the little man who was called John Citizen by Poy. Few recall the burning days of Home Rule: few, indeed, can remember John Redmond standing like a colossus over Asquith, Lloyd George, and the young Churchill. But Poy, in his last days, must often have hearkened back in his mind to these distant years, and he must, I think, have been fully conscious of his own contribution to history—recording for all future generations a picture of our times, and of its greatest figure, unequalled by any other man.

Further reading

“In Search of Churchill’s First Political Cartoon,” 2021

Gary Stiles, “Churchill in ‘Punch’: His Fanciful Hats Helped Fashion His Image,” 2022