Churchill on Joan of Arc: Joan as an Agent of Brexit? Maybe not…

Excerpted from “Angel of Deliverance: Churchill’s Tributes to Joan of Arc,” published by the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the complete article with endnotes and added illustrations, click here.

“Her gleaming, mystic figure…”

Churchill waxed eloquent on Joan of Arc in 1938. His words would likely not pass with today’s minders of Political Correctness:

We see her gleaming, mystic figure in the midst of the pikes and arrows, and it needed not her martyrdom to win her canonization as a saint not only from the Pope but from the modern world. Less enthusiasm would have been excited if, for instance, Joan of Arc had displayed extraordinary proficiency with the crossbow, and if history recounted the numerous victims who had fallen to her unerring aim. We are thrilled by the spectacle of a weak woman leading and encouraging strong men. We do not relish the idea of her killing strong men by some ingenious apparatus; for that strips womanhood of the sex-immunity from violence which is so precious to the dignity of man.

I suppose that will be taken as solid proof that Churchill was an incurable misogynist. In fact, no one had a greater respect for women than he—except perhaps Hilaire Belloc. Men, Belloc said, “come to look on the intelligence of women first with reverence, then with stupor, and finally with terror.” Joan of Arc proved this to the English.

“The winner in the whole of French history”

Churchill in 1938 was writing of Joan in his History of the English-Speaking Peoples. Laid aside during the Second World War, it began appearing in 1956. Describing Joan, Churchill was at his eloquent best:

…an Angel of Deliverance, the noblest patriot of France, the most splendid of her heroes, the most beloved of her saints, the most inspiring of all her memories, the peasant Maid, the ever-shining, ever-glorious Joan of Arc. In the poor, remote hamlet of Domrémy, on the fringe of the Vosges Forest, she served at the inn. She rode the horses of travellers, bareback, to water. She wandered on Sundays into the woods, where there were shrines, and a legend that some day from these oaks would arise one to save France.

It is possible that Churchill’s original opinion was less effusive. In January 1946 he told a literary advisor, Professor Denis Brogan, that he had corrected his Joan of Arc section “after reading Anatole France’s highly documented study.” He hoped that Brogan would not think his praise of Joan “excessive.” Nevertheless, he had admired the Maid a long time.

An Early Appreciation

Churchill was soon aware of Joan’s qualities. In April 1908, he was simultaneously fighting an election in Manchester and courting Clementine Hozier. One of his campaigners was Lady Dorothy Howard, “last of the great Liberal ladies,” a champion of women’s suffrage. “Lady Dorothy arrived of her own accord, alone and independent,” he wrote Clementine (who was also pro-suffrage). “I teased her by refusing to give a decided answer about women’s votes, and she left at once for the North in a most obstinate temper.” Later, after reading his campaign statements, “back she came and is fighting away.” Churchill handily won the seat. “Lady Dorothy fought like Joan of Arc before Orleans,” he wrote Clementine. “…tireless, fearless, convinced, inflexible—yet preserving all her womanliness.”

In the First World War Churchill saw Joan-like qualities in two great Frenchmen, Ferdinand Foch and Georges Clemenceau. The latter represented “the French people risen against tyrants.” Foch expressed the “more ancient, aristocratic heritage of Joan of Arc.” Together he saw them as a “cameo…. But when they gazed upon the inscription on the golden statue of Joan of Arc: ‘La pité qu’elle avait pour le royaume de France’ and saw gleaming the Maid’s uplifted sword, their two hearts beat as one.”

Joan de Gaulle: “But my bishops won’t burn him”

In May 1943, prior to the invasion of Sicily. Churchill cabled Eisenhower: “Many congratulations. …Give my love to Joan of Arc.” I believe but cannot prove this referred to Charles de Gaulle, prickly leader of the Free French. Churchill admired de Gaulle’s fighting qualities, but not his constant interference and demands.

Flight Lieutenant James Coward was an aide at Chequers one night in 1942 when de Gaulle rang. “Oh no,” groaned the Prime Minister, “can’t you put him off? We’ve only started the soup.” De Gaulle insisted, so Churchill went to the phone. He returned livid. “That bloody de Gaulle had the effrontery to tell me that the French looked on him as the second Joan of Arc. I had to remind him that we had to burn the first.” This is likely the origin of Churchill’s famous crack about de Gaulle to Brendan Bracken: “But my bishops won’t burn him.”

Later Churchill was more charitable: “It was said in mockery that he thought himself the living representative of Joan of Arc, whom one of his ancestors is supposed to have served as a faithful adherent. This did not seem to me as absurd as it looked. Clemenceau, with whom it was said he also compared himself, was a far wiser and more experienced statesman. But they both gave the same impression of being unconquerable Frenchmen.”

“His Joan of Arc stance, his pugnacity, his passion…”

On 15 March 1946, after his controversial “Iron Curtain” speech at Fulton, Churchill spoke in New York. Reporters asked, did he regret what he said? Slowly, enunciating each syllable, Churchill replied: “I do not wish to withdraw or modify a single word.” This was said as much to Stalin as his audience, wrote Robert Pilpel. “It brought to mind Joan of Arc’s famous retort to the bullying Duke de la Tremouille: ‘Thou’rt answered, old Gruff-and-Grum.'”

“Winston was not a modern Joan,” his doctor Lord Moran wrote, “exalted and inspired by voices from God.” Like Lincoln, he dominated his colleagues by “sheer moral force.” But another Joan of Arc, Moran considered, was what the British people received. Professor Manfred Weidhorn expands on this thought:

Some of his greatest weaknesses were transmuted by the elixir of global crisis into his greatest strengths. His fervid patriotism, his melodramatic approach to events, his archaic thinking, his theatrical, romantic mode of expression, his Joan of Arc stance, his pugnacity, his passion for obtaining power and leadership, his downright obstinacy, above all his conservative faith in tradition, empire, the British mission and his zeal for war making—these traits were often irrelevant, boring, or obnoxious. But in 1940 nothing else seemed to the point, and he was the only man for the challenge.

Churchill’s book Joan of Arc

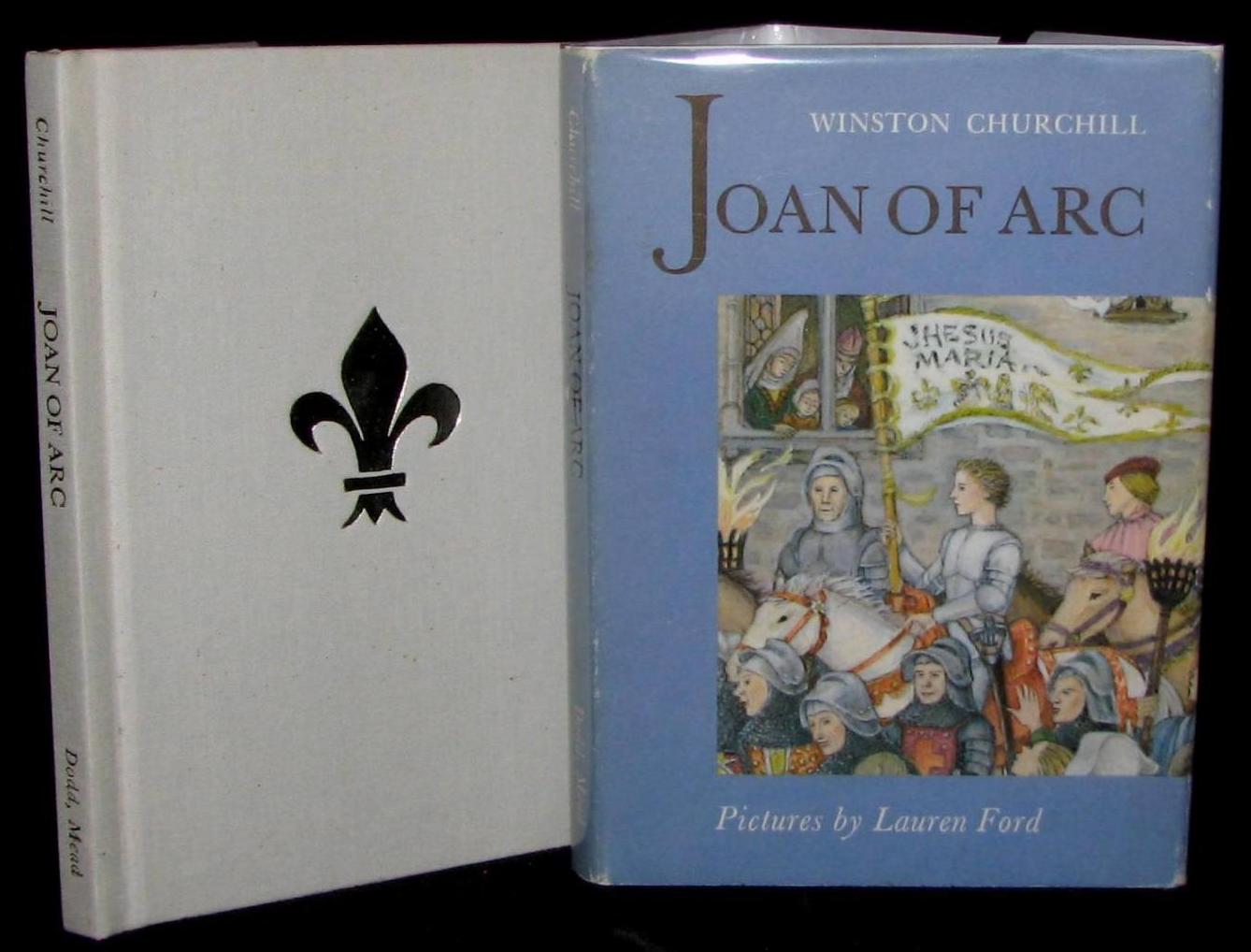

Churchill’s History of the English-Speaking Peoples began serial and book publication in Spring 1956. In May, Paris Match reprinted his passage on Joan as an article, “Jeanne d’Arc” (Cohen C692/1). Then, four years after Churchill’s death, his U.S. publishers Dodd, Mead & Co. issued the same text as a hardback, Joan of Arc (Cohen A279). This lovely little book, beamed at ages 8 and above, cost only $3.50.

The publishers explained in a note that the text opens shortly before the end of the Hundred Years’ War. “The events which are recounted were to lead at last to the breaking forever of England’s hold over France.”

Bibliographer Ronald Cohen says the decision to publish might have had something to do with the illustrator, Lauren Ford. “She herself wrote four books, which she also illustrated: The Little Book about God, Our Lady’s Book, The Ageless Story, and Lauren Ford’s Christmas Book. All had also been published by Dodd, Mead, where she was a fixture.”

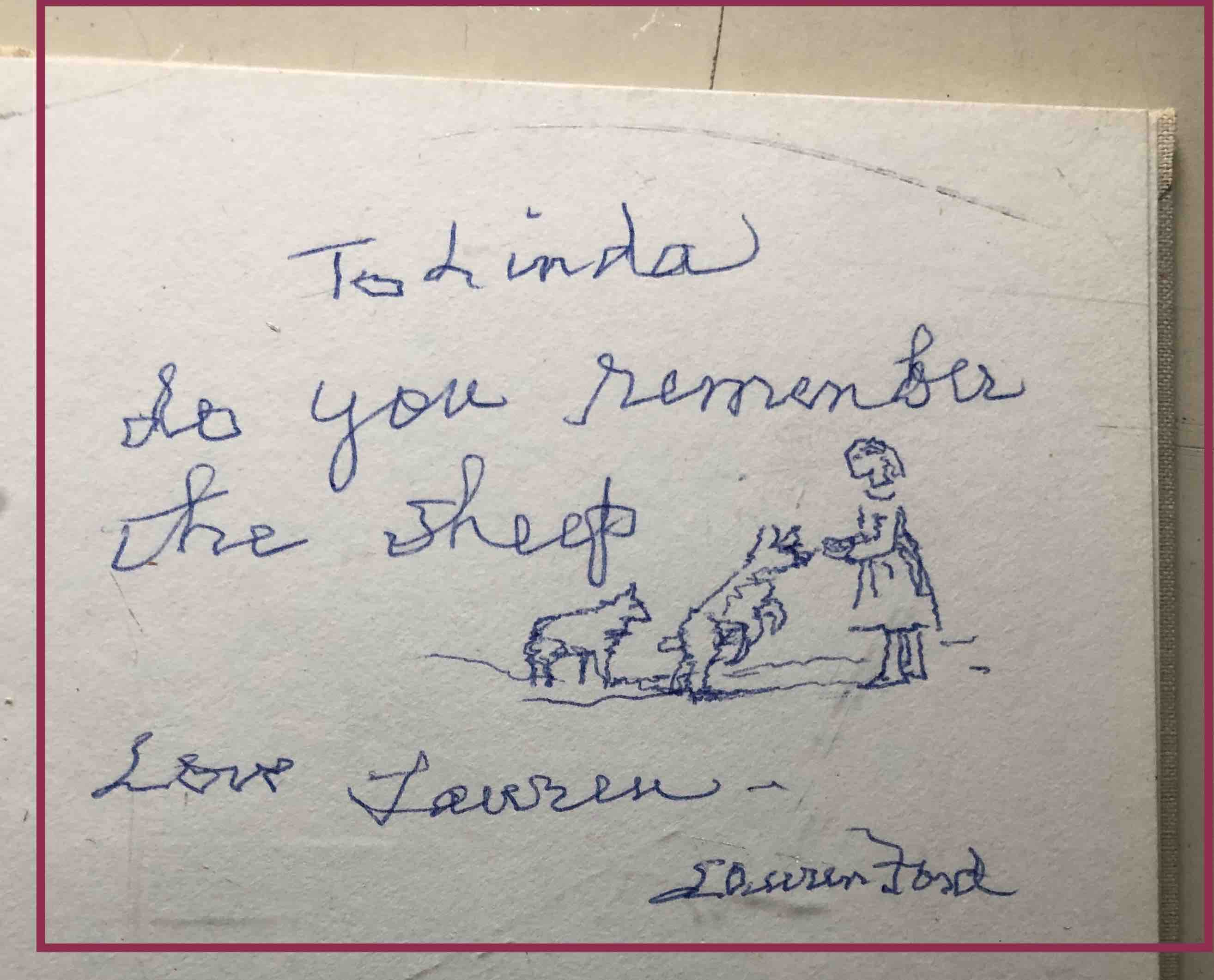

Joan of Arc had only one printing and is the scarcest among extracts from Churchill’s History. As a Churchill bookseller I encountered fewer than a half-dozen copies over twenty years. Marc Kuritz of the Churchill Book Collector has recorded sale prices of $129 to $600, varying with condition. Occasionally one finds a copy inscribed by Lauren Ford herself, often with a charming sketch. These sell for up to $1250.

Joan as agent of Brexit?

Churchill was always ambivalent about France, wrote his last private secretary, Anthony Montague Browne. His love was “sentimental and long-standing, based on personal experience in peace and war. But this did not deter him from taking a firm line with the French if he felt it was required.” And yet in the end, thirty years after he spoke of Joan as “the winner,” Sir Anthony still believed she was:

WSC had quite a pantheon of highly regarded individuals, historical and present. It was unwise to reflect unfavourably on the former, however well-founded subsequent negative evidence might be. I was blasted into orbit with exuberant intellectual energy for making some disparaging remarks about Napoleon and, what was worse, casting doubts on the accuracy of some of the Joan of Arc legend…. His greatest heroine, or indeed hero for that matter, was Joan of Arc.

“Toynbee, rather more tactlessly, argued that Britain’s skepticism about Europe was all the fault of Joan of Arc,” wrote John Ramsden. Joan “taught us to turn our backs on Europe” by inflicting heavy defeats on the invading English in the 15th century. Joan as an agent of Brexit? It seems a stretch.

The French historian François Kersaudy was not quite ready to grant Joan top rank in Churchill’s pantheon: WSC “knew the history of France as well as any Frenchman, and even better than most. With his intensely sentimental and romantic mind, he greatly admired ‘France’s contribution to human freedom and wisdom’; the heroes of French history he admired even more, first and foremost Joan of Arc and Napoleon.”

“Dans le grand drame, il était le plus grand”

But did Churchill rank Joan above Napoleon? Emotionally perhaps, for valiant stands against heavy odds always excited him. In his broad view of French history, however, this writer agrees with Andrew Roberts. Napoleon, whose bust Churchill kept on his desk, stood at his pinnacle. Joan of Arc was close behind. Third in line, I believe, was Clemenceau.

Many historians might place Charles de Gaulle fourth. Churchill had more respect for him than he usually let on, and de Gaulle repaid this on Churchill’s death. “Dans le grand drame,” he wrote Lady Churchill, “il était le plus grand.” In the great drama, he was the greatest.

One thought on “Churchill on Joan of Arc: Joan as an Agent of Brexit? Maybe not…”

Tres bien Richard! ✌🏻🇫🇷

P.s. This is the one book in my collection that my 7 year old son is drawn to. I keep finding it moved slightly. It must have a unique allure; a je ne sais pas! Given its rarity, perhaps I should promptly invest in a lock for my book shelves!

Comments are closed.