Churchill on the V1: Praise for Ingenuity, Horror over Effects

Excerpted from a Q&A post on the V1 for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the unabridged article, please click here.

Robert Lusser and the V1 “Flying Bomb”

A journalist writes about the life of her grandfather, Robert Lusser, chief designer of the V1 flying bomb. She searched for what Churchill said about the V1 in his memoirs of the Second World War. “He mentions the weapon’s destruction in 1944 but nothing of what he thought of the V1 militarily. My grandfather’s papers suggest that Churchill praised the weapon after the war. Even then, what he said must have been considered politically incorrect.”

1954: A “new and ingenious design”

Churchill’s appraisal of the V1 did come after the war, in Triumph and Tragedy (1953-54). From pages 34-35 of the 1954 British edition:

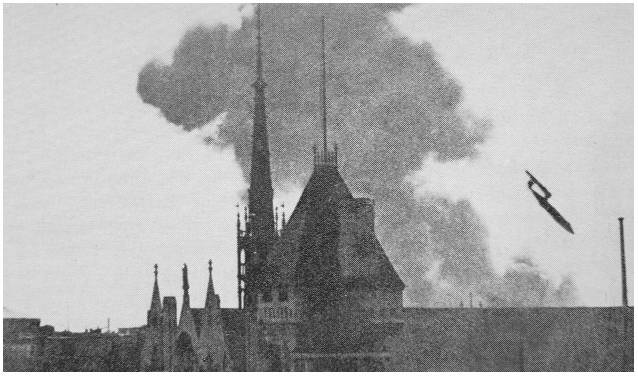

To Londoners the new weapon was soon known as the “doodle-bug” or “buzz bomb,” from the strident sound of its engine, which was a jet of new and ingenious design. The bomb flew at speeds up to 400 mph at heights around 3000 feet, and it carried about a ton of explosive. It was steered by a magnetic compass, and its range was governed by a small propeller, which was driven round by the passage of the bomb through the air. When the propeller had revolved a number of times which corresponded to the distance of London from the launching site, the controls of the missile were tripped to make it dive to earth. The blast damage was all the more vicious because the bomb usually exploded before penetrating the ground.

It imposed upon the people of London a burden perhaps even heavier than the air raids of 1940 and 1941. Suspense and strain were more prolonged. Dawn brought no relief, and cloud no comfort. The man going home in the evening never knew what he would find…. There was little that he could do, no human enemy that he could see shot down.

1944: “One person per bomb”

The Churchill Documents, vol. 20, Normandy and Beyond, May-December 1944, contain many references to the V1. Churchill’s first public statement came on July 6th. Britain, he said, had known about the V1 for a year. Compared to Allied raids over Germany, he said, the V1 was a pinprick—but a frightful one, because of its surprise nature:

…but people have just got to get used to that. [Hon. Members: “Hear, hear.”] Everyone must go about his duty and his business whatever it may be—every man or woman—and then, when the long day is done, they should seek the safest shelter that they can find and forget their care in well-earned sleep.

We must neither underrate nor exaggerate. In all up to 6 a.m. today, about 2,750 flying bombs have been discharged… A very large proportion of these have either failed to cross the Channel or have been shot down and destroyed…. Nevertheless, the House will, I think, be favourably surprised to learn that the total number of flying bombs launched from the enemy’s stations have killed almost exactly one person per bomb. That is a very remarkable fact, and it has kept pace roughly week by week.

The threat subsides

Churchill did not then praise V1 technology, but questioned its morality: “The introduction by the Germans of such a weapon obviously raises some grave questions upon which I do not propose to trench today.” He was sure, meanwhile, that London “will never fail and that her renown, triumphing over every ordeal, will long shine among men.”

What Londoners were going through then adds some perspective to the relative importance of what excites its citizens today.

The V1 was not hard to destroy through anti-aircraft or fighter fire. But launches in mid-1944 were frequent enough to allow many to get through. They killed 6000 Londoners and 1.5 million were evacuated. By mid-September V1 damage had faded as Hitler launched the V2 rocket, a much more formidable threat. V2 attacks killed 3000, but as more launching sites were captured in France, the danger eased.

A quality of detached admiration

Churchill’s 1953-54 appraisal of the V1 as “ingenious” illustrates a rare aspect of his character: the detachment to acknowledge the cleverness of enemies. Similarly, in 1940, he referred to Germany’s Blitzkrieg as “a remarkable combination of air bombing and heavily armoured tanks.” In 1942 he said of Field Marshal Irwin Rommel during the North Africa campaign: “We have a very daring and skillful opponent against us, and, may I say across the havoc of war, a great general.”

That took listeners by surprise and caused consternation. Churchill in his memoirs was unrepentant. Rommel’s “ardour and daring inflicted grievous disasters upon us,” he admitted. Nevertheless, “he deserves the salute which I made him….

…although a loyal German soldier, he came to hate Hitler and all his works, and took part in the conspiracy of 1944 to rescue Germany by displacing the maniac and tyrant. For this he paid the forfeit of his life. In the sombre wars of modern democracy chivalry finds no place…. Still, I do not regret or retract the tribute I paid to Rommel, unfashionable though it was judged.

By 1953, when Churchill pronounced the V1 “ingenious,” its creator was in America with Wernher von Braun’s rocketry team. Lusser’s theories on the contribution each component makes to the overall reliability of a rocket system became known as Lusser’s Law. For the nonce, they punctured von Braun’s complicated scheme for a Moon landing. Robert Lusser almost lived seen the landing happen. He died in January 1969, six months before Apollo 11 landed on the Sea of Tranquility.

Further Reading

“The Flying Bombs,” in Robert Lyons and G.C.B. Dodds, “Private Secretary G.C.B. Dodds Remembers Churchill in Wartime,” 2019.