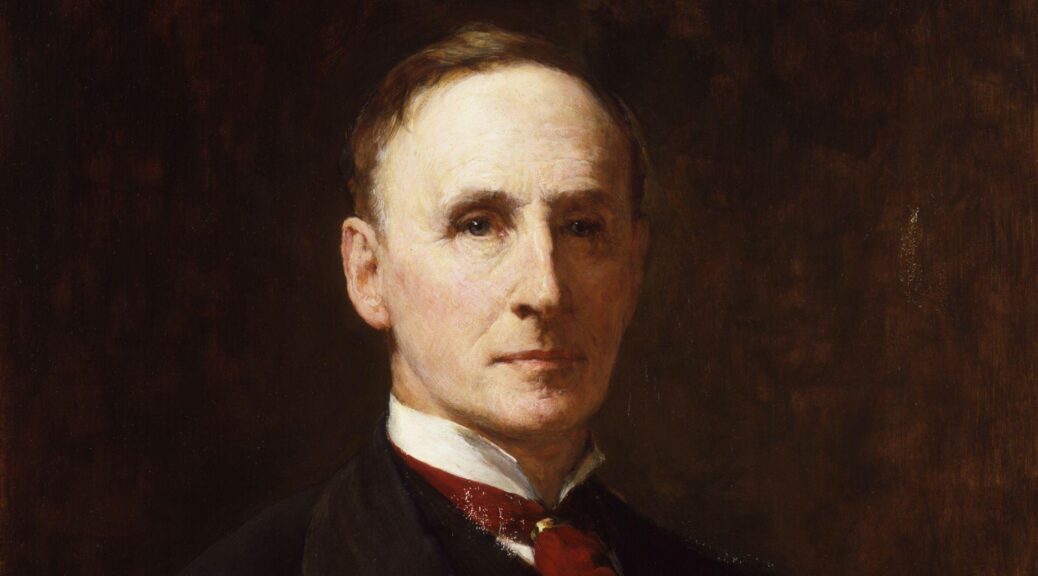

John Morley, Victorian Eminence: “Such Men Are Not Found Today”

Excerpted from “Great Contemporaries: John Morley, Giant of Old,” written for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original article with endnotes and more images, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, and fill in your email in the box entitled “Stay in touch with us.” Your email address is not given out and remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Britain’s Antonine Age

The columnist George Will quoted a famous line by Churchill: “The leadership of the privileged has passed away, but it has not been succeeded by that of the eminent.”

The rest of Churchill’s remark was worth including: “The pedestals which had for some years been vacant have now been demolished. Nevertheless, the world is moving on, and moving so fast that few have time to ask, ‘Whither?’ And to these few only a babel responds.”

By “privileged,” Will presumably referred to the old aristocracy that governed Victorian Britain, not the pampered elites who govern us today. Churchill was referring to John Morley. “Such men,” he concludes sadly, “are not found today.”

Morley was born in 1838, during a century of peace, prosperity and progress. This, Churchill tells us, “was the British Antonine Age…

The French Revolution had subsided into tranquillity; the Napoleonic Wars had ended at Waterloo; the British Navy basked in the steady light of Trafalgar, and all the navies of the world together could not rival its sedate strength. The City of London and its Gold Standard dominated the finance of the world. Steam multiplied the power of man; Cottonopolis was fixed in Lancashire; railroads, inventions, unequalled supplies of superior coal abounded in the island; the population increased; wealth increased; the cost of living diminished; the conditions of the working classes improved with their expanding numbers.

“Unquenchable racial animosity”

John Morley was born in Blackburn, Lancashire, the son of a doctor who wanted him to become a clergyman. Disenchanted with the “High Church” and quarreling with his father, he left Oxford without an honors degree and pursued Law. He was called to the bar by Lincoln’s Inn in 1873. A few years later, to his “long and enduring regret,” he became a journalist. From 1880 to 1883 he edited the radical-Liberal Pall Mall Gazette.

A strong supporter of Gladstone, Morley in Parliament was a fearless opponent of State intervention. It was wrong “to give the Legislature, which is ignorant [and] biased in these things…the power of saying how many hours a day a man shall or shall not work.” (One wonders what he would say today to a government that governs everything.

After six years out of power, Gladstone returned in 1892 and made Morley Chief Secretary for Ireland. Churchill, then a Tory supporter of the Second Boer War, nevertheless admired Morley’s “fierce, moving phrases” of indictment:

Thousands of our women have been made widows; thousands of children are fatherless…. The expenditure of £150 million has brought material havoc and ruin unspeakable, unquenched and for long unquenchable racial animosity, a task of political reconstruction of incomparable difficulty, and all the other consequences which I need not dwell upon [in a] war of uncompensated mischief and of irreparable wrong.

Morley’s opposition to adventures abroad prefigured his attitude toward a far greater war to come.

“A quality about his rhetoric”

In 1904 Churchill “crossed the floor” to the Liberals, who swept into office in January 1906. Morley was Secretary of State for India when young Winston became Under-Secretary for the Colonies. In harness, they became friends, and Churchill was eloquent in his praise:

As a speaker, both in Parliament and on the platform, Morley stood in the front rank of his time. There was a quality about his rhetoric which arrested attention. He loved the pageantry as well as the distinction of words, and many passages in his speeches dwell in my memory…. His gifts of intellect and character were admired on all sides.

There is an affinity between their mutual combination of firmness and magnanimity toward colonial peoples. While opposing lawless rioting, Morley sponsored the 1909 India Councils Act, bringing Indians to his Council and those of Madras and Bombay. This early step toward self-rule mirrored Churchill’s views.

“Master of English prose”

In 1908 the new prime minister, H.H. Asquith, moved Morley to the Lords, where he fought for Liberal reform budgets. He retained the India Office, but by 1910 yearned for retirement. Churchill pleaded that he be kept in the Cabinet, so Asquith appointed him Lord President of the Council. There he campaigned for the 1911 Parliament Act, limiting the powers of the House of Lords.

Morley linked young Winston to the father he worshipped, while adding qualities of his own. He was solid for “great doctrines”: Free Trade, Irish Home Rule, a social safety net. Churchill saw in him “a master of English prose, a practical scholar, a statesman-author, a repository of vast knowledge.” Despite their 35 years difference in age, they worked together “in the swift succession of formidable and perplexing events.” Eventually those events would separate them.

“Gently, gaily almost, he withdrew…”

Predictably, Morley opposed continental entanglements, distrusting the system of alliances that impelled the world toward Armageddon. He turned 75 in 1914, frail but not unconscious of what Churchill called “the madness sweeping across Europe.” As Germany and France clanked towards battle, the Liberal Cabinet was divided. But Germany’s invasion of Belgium, and the possibility of a German fleet in the Channel, turned opinion.

Winston Churchill tried to assure Morley that events gave them no choice. His pacifist friend was sympathetic but unyielding. “You may be right,” he said. “But I should be no use in a War Cabinet. I should only hamper you. If we have to fight, we must fight with single-hearted conviction. There is no place for me in such affairs.” There was no turning him. “Gently, gaily almost, he withdrew from among us,” Churchill wrote, “never by word or sign to hinder old friends or add to the nation’s burden.”

“I do not ask myself if I am a good European”

Morley was 80 when peace returned, but no less doubtful about the so-called “War to End Wars.” Like Churchill, he criticized President Wilson’s naïveté at Versailles. He had always been a Little Englander, a Home Ruler. He did not object to the new countries created after the war. But he had no faith in a concert of nations to keep the peace. When asked in 1919 about the Covenant of the League of Nations, Morley said: “I have not read it, and I don’t intend to read it. It’s not worth the paper it’s written on. To the end of time it’ll always be a case of ‘Thy head or my head.’ I’ve no faith in these schemes.” He was more right than he knew.

While Churchill had hope for European powers to keep the peace, Morley remained scornful. When a prominent Liberal praised someone as “a good European,” Morley quipped: “When I lay me down at night or rise in the morning, I do not ask myself if I am a good European.” Nations, he insisted, would always act in their own interests. If that coincided with the world’s, it was a mere lucky coincidence. When Ireland erupted again in 1921 he declared: “If I were an Irishman I should be a Sinn Feiner.” When asked, “And a Republican?” Morley said “No.” Home Rule within the Empire was as far as he would go.

“I foresee…Winston leading the Commons”

Toward the end, Morley seemed to accept Churchill’s view of him as a Victorian eminence, against which modern politicians were no match. In postwar politics, Morley said, “One man is as good as another—or better.” Yet he still had hopes for his young colleague:

I foresee the day when Birkenhead will be prime minister in the Lords with Winston leading the Commons. They will make a formidable pair. Winston tells me Birkenhead has the best brain in England…. But I don’t like Winston’s habit of writing articles, as a Minister, on debatable questions of foreign policy in the newspapers. These allocutions of his are contrary to all Cabinet principles. Mr. Gladstone would never have allowed it.

His prediction would have required Churchill to change parties again. Churchill did, but Birkenhead died young, in 1930. Still, Morley was half right: Winston did lead the Commons…and the nation. Alas, that was in another war he would have hated and feared. And, contra Mr. Gladstone, Churchill kept writing—fortunately. Some of what he wrote was in tribute to his old friend.

“Two hundred definitions of Liberty”

Churchill considered John Morley “among the four most pleasing and brilliant men to whom I have ever listened…. There was a rich and positive quality about Morley’s contributions, and a sparkle of phrase and drama which placed him second to none….”

Morley died in 1923, not to be replaced. Churchill mourned his loss: “The tidal wave of democracy and the volcanic explosion of the war have swept the shores bare.” No one better resembled or recalled “the Liberal statesmen of the Victorian epoch.” Morley was not born to privilege; he earned it. He deployed “every intellectual weapon, of the highest personal address, and of all that learning, courtesy, dignity and consistency could bestow.”

Churchill wrote: “Each succeeding generation will sing with conviction the Harrow song, ‘There were wonderful giants of old.’ Certainly we must all hope this may prove to be so.”

Morley pronounced the epitaph for his age in May 1923, four months before he died. His words sound more like 2023:

Present party designations have become empty of all contents…. Vastly extended State expenditure, vastly increased demands from the taxpayer who has to provide the money, social reform regardless of expense, cash exacted from the taxpayer already at his wits’ end—when were the problems of plus and minus more desperate?

Powerful orators find “Liberty” the true keyword. But then I remember hearing, from a learned student, that of “liberty” he knew well over 200 definitions. Can we be sure that the “haves” and the “have-nots” will agree in their selection of the right one? We can only trust to the growth of responsibility; we may look to circumstances and events to teach their lesson.