How Winston Churchill Preserved the Dream of Israel: July, 1922

The Dream of Israel : An earlier version of this article appeared in The American Spectator on June 30th. There were some interesting comments. Click the link to read.

Herein, some edits of the edits, which diverged slightly from the draft. The published subtitle was, “Here’s betting he would have loved America’s new embassy.” (Never bet on what Churchill might love or not love.) It’s worth noting that the U.S. Embassy is in West Jerusalem. In a settlement, there could also be an Arab seat of government in East Jerusalem. RML

Britain and Israel

Prince William landed in Israel June 25th for the first royal visit to the country. In many respects this marks a historic British recommitment. Churchill’s resolve nearly a century ago ensured that an Israel would exist.

British support of Israel is largely attributed to Arthur James Balfour, for whom the Balfour Declaration is named. By it, Britain backed a “Jewish national home” after the end of World War I. But few know or note that Winston Churchill contributed more to what became Israel than Arthur Balfour. His words to the House of Commons, spoken on American Independence Day, 1922, saved the national home from extinction.

Controversy over the creation of a Jewish state had been building for several years before Churchill made his case on the 4th of July. The Zionist movement, founded by Theodor Herzl in 1897, strove to reestablish a Jewish community in that part of Palestine which was the ancient homeland of the Jews. In 1920, Churchill wrote that if “there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State…an event would have occurred in the history of the world which would, from every point of view, be beneficial.”

Not everyone agreed. Britain had fought the war in part to defeat the Ottoman Empire. Arabs, many argued, should rule there exclusively.

Mandate of Palestine

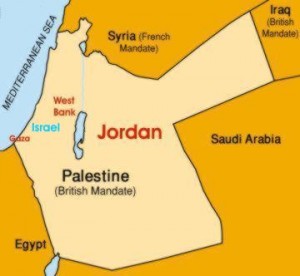

In the peace that followed World War I, the new League of Nations provided legal status, called “mandates,” for territories transferred from the control of one country to another. The League defined mandates as “waypoints toward independence.” Cynics said it was a polite term for colony-building. Britain received the Mandate of Palestine, including what is now Jordan and Israel. Its capital was Jerusalem.

As colonial secretary in 1921, Churchill established Jordan in six-sevenths of the Mandate and backed a Jewish homeland in the remainder, where the Zionists had largely settled. “One principle of the Balfour declaration,” he told a Jewish delegation, “is that the process of the establishment of a national home for the Jews is to be without prejudice or unfairness to the Arab and Christian inhabitants.” (See Warren Dokter, Churchill and the Islamic World.) Many in Parliament objected. In 1922, they tried to cancel the Balfour Declaration — with warnings that sound remarkably familiar.

In 1922, two-thirds of the House of Lords voted to reject Balfour’s promise, declaring that a Jewish homeland was unacceptable “to the sentiments and wishes of the great majority of the people of Palestine.” The Arabs, said Lord Sydenham, a former colonial administrator, “would never have objected to the establishment of more colonies of well-selected Jews; but, instead of that, we have dumped down 25,000 promiscuous people on the shores of Palestine…. What we have done is… to start a running sore in the East, and no one can tell how far that sore will extend.”

Pushback

In a bravura performance in the House of Commons on 4 July 1922, Churchill turned things around, hurling the earlier words of doubters back at them. Lord Sydenham, he noted, had earlier hoped “…to free Palestine from the withering blight of Turkish rule, and to render it available as the national home of the Jewish people, who can restore its ancient prosperity.”

The Conservative stalwart Sir John Butcher, Churchill said, “has just addressed us in terms of biting indignation.” Then he quoted what Butcher had said in 1917: “I trust the day is not far distant when the Jewish people may be free to return to the sacred birthplace of their race, and to establish in the ancient home of their fathers a great, free, industrial community….”

Sir William Joynson-Hicks, a popular Tory and future government minister, had led the attack on the Balfour Declaration. Churchill flung back at “Jix” his words from 1917: “I will do all in my power to forward the views of the Zionists, in order to enable the Jews once more to take possession of their own land.” Churchill concluded: “If, over the portals of the new Jerusalem, you are going to inscribe the legend, ‘No Israelite need apply,’ then I hope the House will permit me to confine my attention exclusively to Irish matters.”

Turnback

It was, as the historian Paul Johnson wrote, “one of [Churchill’s] greatest speeches.” And it had the intended effect. The House of Commons voted 292-35 to continue Balfour’s Palestine policy, reversing the House of Lords. Johnson considers the speech a watershed: “Without Churchill, it is very unlikely that Israel would ever have come into existence.”

In 1922, Churchill rejected a demand by Arabia’s King Ibn Saud to stop Jews from settling in Palestine. He proposed a compromise, allowing immigration based on Palestine’s economic capacity. As a result, 400,000 Jews escaped from Europe before World War II.

In 1939 Churchill opposed a British white paper again attempting to slow immigration. In 1941, he exempted Palestine from the Atlantic Charter. This declared the right of all peoples to the government of their choice. He explained to President Roosevelt that the Arabs would claim a majority and block Jewish immigration.

Aftermath

Churchill retained sympathy for Arab aspirations and was not unafraid to criticize Jewish extremism. Outraged when his friend Lord Moyne, British minister of state in Cairo, was killed by Stern Gang (Lehi) militants in 1944, he urged Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann to suppress extremism, lest Zionism only produce “a new set of gangsters worthy of Nazi Germany.” Weizmann agreed.

Churchill’s speeches after the founding of Israel were consistently supportive. On his 75th birthday, he received a message from David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister: “Your words and your deeds are indelibly engraved in the annals of humanity. Happy the people that has produced such a son.”

In 2015, the Simon Wiesenthal Center and Museum of Tolerance in New York celebrated Churchill’s

everlasting love and affection for the Jewish people.… Over 600 people watched with an awe that transcends generations…. [This] signaled gratitude to a family that bore much criticism, heartache and professional consequence for its steadfast support of our people and our national home.

Nearly 110 years ago, Churchill said, “Jerusalem must be the [Jews’] only ultimate goal. When it will be achieved it is vain to prophesy… That it will some day be achieved is one of the few certainties of the future.”For Britain as for America, it looks as though that day has arrived. But let us remember to whom we are really indebted for these achievements.

One thought on “How Winston Churchill Preserved the Dream of Israel: July, 1922”

Excellent and informative information. I was not aware of the depth of Churchill’s influence.

Comments are closed.