Introduction to “The Dream”: Churchill’s Haunting Short Story

The Dream is republished (from Never Despair 1945-1965, Volume 8 of the official biography) by the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. To read it in its entirety, click here.

The Dream…

… is the most mysterious and ethereal story Winston Churchill ever wrote. Yet the more we know about him, the better we may understand how he came to write it.

Replete with broad-sweep Churchillian narrative, The Dream contains many references to now-obscure people, places and things. The new online version published by Hillsdale provides links to all of them. You need only click on any unfamiliar name or term for links to online references. After reading the story, click here for a thoughtful appreciation by Katie Davenport, a Churchill Fellow at Hillsdale College.

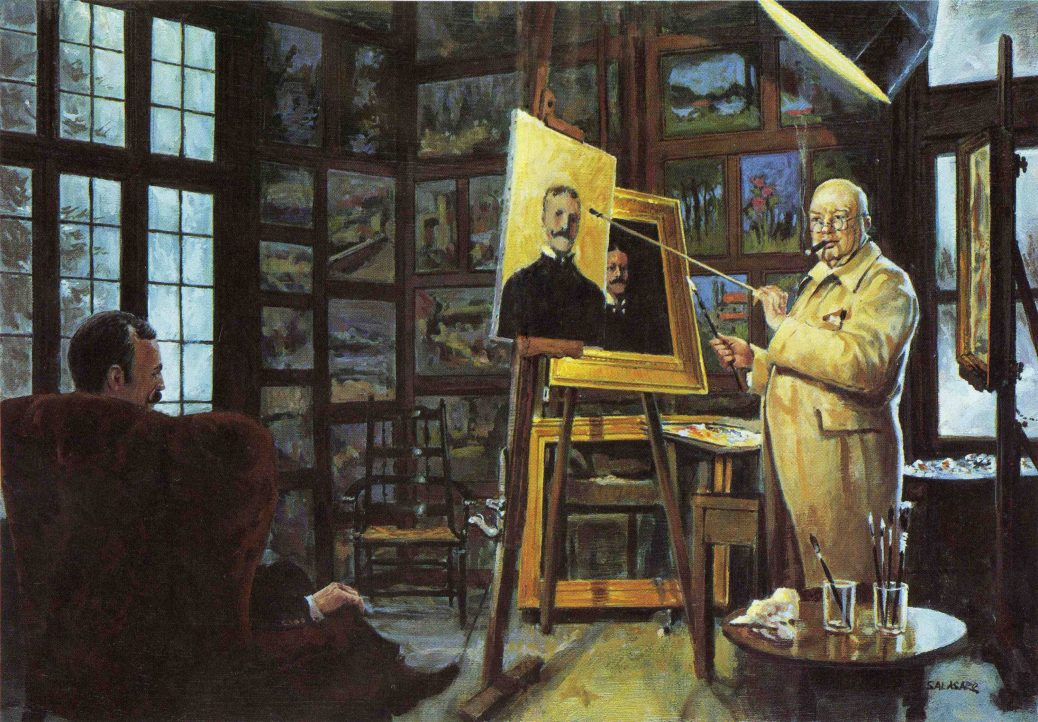

Churchill wrote The Dream in 1947, a low point in his political career. Two years earlier, British voters had turned his Conservative Party out of office. The former Prime Minister was now a frustrated Leader of the Opposition. But political reverses often brought out the best in his writing. Churchill’s great war memoir, The World Crisis, began appearing at a similar low point, after he had lost his seat in Parliament in 1922-24. Marlborough, his noble biography, was written in the 1930s, as he grieved over the nation’s failure to heed his warnings about Hitler.

Origins

The poignancy of The Dream is heightened by the appearance of Winston’s father, Lord Randolph Churchill. Dead in 1895 at the age of forty-six, Lord Randolph had not lived to see, nor indeed ever imagined, his son at the pinnacle of their country’s affairs.

Lord Randolph’s own career had lasted scarcely twenty years. Elected to Parliament in 1874, he rose meteorically. By 1884 he was Leader of the House of Commons and Chancellor of the Exchequer. But in 1886 he resigned over a trivial matter, never to rise again. Compared with Winston, Randolph was a footnote in British history.

The boy Winston worshiped his father from afar, but never conquered Lord Randolph’s disdain. It was his lifelong regret that his father did not live to see what he had achieved. It is part of the artistry of this tale that the inquisitive young father of forty never learns what his seventy-three-year-old son became.

The Dream was first mentioned during a family dinner at Chartwell, Churchill’s beloved home in the lush Kentish countryside, twenty-five miles outside London. He entitled the story “Private Article,” showing it only to his family, resisting their urgings that it be published. In his will he bequeathed the text to his wife, who donated it to Churchill College, Cambridge. On the first anniversary of his funeral, 30 January 1966, it was published in The Sunday Telegraph. The Dream has also appeared as a stand-alone volume in two private printings and a fine 2005 edition by Levenger Press.

Reactions

Winston Churchill was a man of transcendental powers. He could, it seems, peer beyond reality. Jon Meacham, author of the seminal Franklin and Winston, believes The Dream sheds light on Churchill’s ability to put a better face on things than they really were: to revere a father who overlooked him; to revere Roosevelt, who, in their later encounters, was less than forthright.

Margaret Thatcher, in my view the greatest British prime minister since Churchill, took a right and kind view of The Dream’s Victorian lurches—which are anything but politically correct. In 1993 I presented her with a private printing. She thanked me in her own hand the next day. “I read it in the early hours of this morning,” she wrote, “and am totally fascinated by the imagination of the story and how much it reveals of Winston the man and the son.” Later I asked what she thought of Churchill’s remark about women in the House of Commons: “They have found their level.” Lady Thatcher beamed: “I roared at that one.”

While vague about the hereafter, Churchill always held that “man is spirit,” and believed in a kind of spiritual connection with his forebears. On 24 January 1953, he told his private secretary, John Colville, that he would die on that date—the same date his father had died in 1895. Twelve years later Churchill lapsed into a coma on January 10th. Confidently, Colville assured The Queen’s private secretary: “He won’t die until the 24th.” Unconscious, Churchill did just that.

One question about The Dream that tantalized his family is whether the story was really fiction. When asked this question, Sir Winston Churchill would smile and say, “Not entirely.”

One thought on “Introduction to “The Dream”: Churchill’s Haunting Short Story”

Beautifully done Richard – a real joy to read.

Celia Lee author of

THE CHURCHILLS A Family Portrait

Comments are closed.