Churchill and his Taxes: “Genius has many outlets”

Taxes and the Man

On the matter of Churchill’s taxes, a friend quotes a very good historian we both respect: “His relationship with the taxman was scandalous. As Chancellor of the Exchequer, Churchill exploited tax loopholes and he retired as an author on more than one occasion to avoid paying tax.”

My friend writes: “Surely what Churchill did was just on the borderline of tax-optimization? It would only be scandalous if it was tax evasion. But it was in fact legal.”

I am not an expert on Churchill’s taxes. I accept that he took whatever measures that were open and legal to minimize the bite. It is true that he “retired” as a writer for tax purposes from time to time. Readers should refer to David Lough’s comprehensive No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money. With regard to his World War II memoirs, see also David Reynolds, In Command of History: Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War.

Paintings not Articles

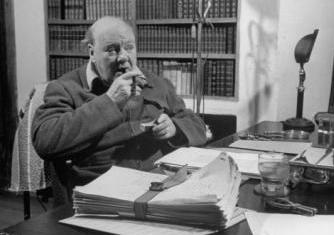

Of interest is a note by Walter Graebner, Churchill’s editor for Life magazine’s serialization of his war memoirs. In his delightful 1965 memoir, My Dear Mister Churchill, Graebner recalls a visit to WSC in the autumn of 1945. Having left Downing Street following the July general election, the Churchills were staying at Claridges, before acquiring and moving into 28 Hyde Park Gate.

Of interest is a note by Walter Graebner, Churchill’s editor for Life magazine’s serialization of his war memoirs. In his delightful 1965 memoir, My Dear Mister Churchill, Graebner recalls a visit to WSC in the autumn of 1945. Having left Downing Street following the July general election, the Churchills were staying at Claridges, before acquiring and moving into 28 Hyde Park Gate.

Five dollars a word! That’s what Life offered for his articles. This is $67 a word in today’s money—a figure that makes the heads of us writers swim. Graebner’s comments also bear on the tax issue, and Churchill’s tactic of “retiring” from writing during periods of high tax vulnerability:

***

Miss Hill [WSC’s secretary] opened the door and asked me to take a seat in the drawing-room to the left, adding, “Mr. Churchill will be here in a moment.” I looked for a chair, but none was empty. Every chair and sofa in the room had a painting on it, so there was nothing for me to do but wander around and examine the collection. Here was showmanship at its best. Churchill had carefully set up a private exhibition, and I was his audience.

Just as I had finished inspecting the last of about a dozen pictures, Churchill walked in wearing his blue zip suit, his face pink and powdery after a shave, his pale blue eyes smiling. “I’ve been on holiday in Italy and the South of France as you may know,” he began, “and while there I made these paintings which you see—er—in this gallery—on private view. You wrote to me a short time ago about writing some articles….”

Marching up and down the room he continued: “That was a very good offer you made me—very flattering. I wish I could have accepted it. It’s the best offer I’ve ever had. Five dollars a word I think it works out at. That’s very good. But I am not in a position to write anything now—perhaps later—but not now. I have gone into the whole thing very carefully with my advisers and they tell, me that if I come out of retirement—you see I’ve been in retirement ever since the election when the people turned me out—and write anything now, I would have to pay taxes of nineteen and six in the pound, so what’s the use?”

“Genius has many outlets”

The pound was then worth $4; 19 shillings sixpence or $3.90 represents 97.5% of it. Of course those were wartime rates, and the highest bracket. Still, Churchill’s remark is a stunning illustration of the long-running claim of “supply siders” that high taxes actually diminish government revenue by discouraging the productive from working harder. But I digress. Graebner continues:

Then, gesturing towards the paintings, he concluded: “But these are something else again. Do you think your people might like to publish them—that is, to take them in place of one of the articles? I would like such an arrangement better for the time being, as the income, I am advised, would be considered as a capital gain and therefore non-taxable.”

The point was clear. Churchill was offering for $25,000 the reproduction rights to the paintings he had made on holiday. It was agreed that I would communicate with my editors. Before leaving I congratulated him on the excellence of his pictures, expressing surprise that he could find the time to take up painting on top of all his other work. Behind an enormous grin he murmured: “Genius has many outlets.”

Evidently they hadn’t thought of taxing capital gains in Britain then. And for the record, $25,000 in 1945 is equal to $338,000 in today’s money.

Do not take Churchill’s wisecrack out of context as the expression of a braggart. Many such quips are in Graebner’s book. He smiled when he said those things. Winston Churchill was not a braggart. But he could not resist his little joke.