Churchill Now: A Life Worth Contemplating in the Digital Age

“Churchill Now” is excerpted from an article for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the unabridged text including endnotes, please click here. To subscribe to posts from the Churchill Project, click here, scroll to bottom, and fill in your email in the box entitled “Stay in touch with us.” Your email address is never given out and will remain a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

* * *

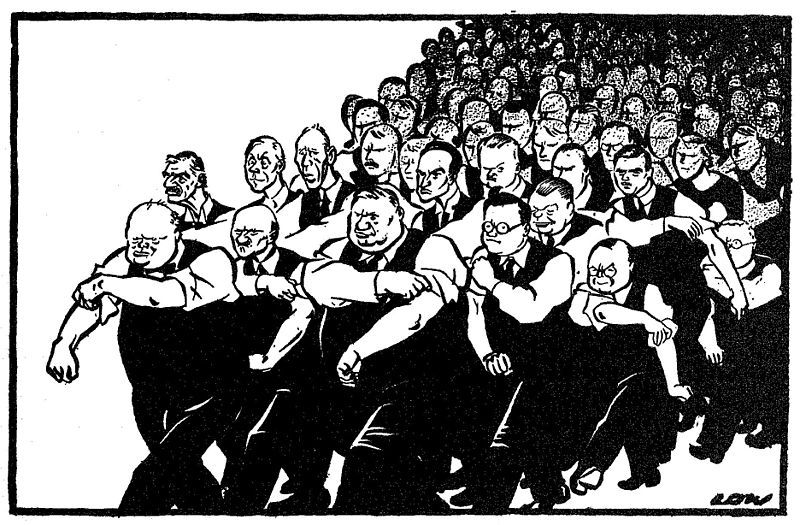

“The leadership of the privileged has passed away, but it has not been succeeded by that of the eminent. We have entered the region of mass effects. The pedestals which had for some years been vacant have now been demolished. Nevertheless, the world is moving on, and moving so fast that few have time to ask, ‘Whither?’ And to these few only a babel responds.” —Winston S. Churchill, “John Morley,” in Great Contemporaries (1937)

The challenge now

Almost half a century since his death, those who actually knew Churchill have dwindled to a handful. Yet his name is all over the news. When the last person who knew him dies, Churchill will live on—like Washington, Lincoln, the Roosevelts and, on the darker side, Hitler, Mao and Stalin. There will be plenty of detractors to catalog his faults. There always have been.

Now for some young people, his times must seem like the blue distance of the Middle Ages. But anyone who thinks Churchill belongs to history doesn’t follow the news. We who know something about him therefore have an opportunity. It’s called the Internet. In this bubbling, digital soup, Churchill can say anything, or do anything, from deserting a sinking ship to fire-bombing Dresden—quoted, or misquoted, by anonymous authors.

But the truth matters, or it should. Who was the real Churchill? What did he stand for? We’ll not get the answers from obscure zealots with wi-fi connections.

The digital warp

His name elicits 40 to 50 million browser hits, which may often confuse truth with fiction. A recent survey of British schoolchildren revealed that nearly half thought Churchill was a mythical figure, like Sherlock Holmes. This says something about public education, which too often simply omits Churchill.

Those who know he existed frequently misconstrue him. Take for example his injections of humor into serious situations. After Hitler invaded Russia and was confronted by the Russian winter, Churchill cracked: “He must have been very loosely educated.” Such remarks caused offense back then. Now, some still do.

Web-crawlers now are sometimes perplexed at Churchill’s unexpected outbursts of magnanimity—because it is now so rare a quality. There was his remark about Erwin Rommel, commander of the German Afrika Korps, in the heat of battle in 1942: “We have a very daring and skillful opponent against us, and, may I say across the havoc of war, a great general.” That still earns the outraged complaint that he praised a Nazi. Ignorance again: The real Rommel “came to hate Hitler and all his works,” conspired in an assassination plot, and paid for it with his life. The real Churchill never hid his admiration for persons of quality, even among his opponents.

Quips and wisecracks

Churchill’s offhanded asides often give people entirely the wrong impression, causing them to draw false conclusions. Mainly this is because they are quoted out of context, the circumstances unexplained. The late William F. Buckley, Jr. offered an example:

Working his way through disputatious bureaucracy from separatists in Delhi, Churchill exclaimed, “I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion.” I don’t doubt that the famous gleam came to his eyes when he said this, with mischievous glee—an offense, in modern convention, of genocidal magnitude.

Mr. Buckley had no idea how prescient he was. Years later, a book appeared accusing Churchill of willfully exacerbating the 1943 Bengal famine—which he actually tried to alleviate. And that private wisecrack of his has been used to prove he hated Indians. It was recorded, incidentally, by Leo Amery in his diary, which makes it hearsay. We do know that Churchill loved to tweak the excitable Amery with an occasional outrageous poke.

Understanding the man

The real Churchill is a complicated subject, with a 50-year career and masses of documentation. Understanding him takes determination. Alas, a number of people now are determined to believe anything. They can probably find more pure rubbish about Churchill on the Internet than in all critical books of the last century. Of course, some of the criticisms are well-founded. Churchill’s faults like his virtues were on a grand scale. But the latter far outweigh the former.

Through the work of the Hillsdale College Churchill Project and other institutions, the truth is having some effect. Public figures are more cagey when they quote Churchill nowadays. Sometimes they even ask for verification. Hillsdale devotes a whole category on its Churchill site to “Truths and Heresies.” A leading British historian writes, “May I say these pages are very good? Really forensic & unanswerable.”

It is good to seek out the real Churchill. After all, he is fun to study. He provokes thought. He represents many sides on many questions. Churchill’s specific policies may not apply today. But as Paul Addison wrote, his writings and speeches are full of reflections and philosophy: “It is rare to discover in the archives the reflections of a politician on the nature of man.”

Just get it right

Here’s a modest rule: Criticize and analyze him by all means, but be sure of your sources. Churchill himself liked to quote a professor who told his students: “Verify your quotations.” One can only wish Twitter and Facebook users would actually do that.

One of the least appreciated periods of his life, was as Leader of the Opposition in 1945-51. On issue after issue, he excoriated Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee, of whom Churchill was very fond personally. Attlee had been his devoted deputy prime minister during the war.

It is not true, therefore, that Churchill once said, “an empty car drew up and Clement Attlee got out.” When confronted with this alleged crack he replied that Attlee was a gallant and devoted servant of the Crown, and he would never say that about him. It is important to understand this now-rare quality of collegiality. Whatever the political quarrels, Churchill never indulged in personal attacks, and regarded his opponents as servants of the nation. That is something we have lost, at least in the present.

Optimistic realist

Churchill was unabashedly proud of his country, and of all the good Britain, America and the Commonwealth, including India, had accomplished. But he was not sure about the future. A fair description of him would be “optimistic realist”—especially about mankind, the same imperfect being, he declared, presented by science with increasingly potent and dangerous toys. It is hard to believe he spoke these words over 70 years ago:

…the spate of events with which we attempt to cope, and which we strive to control, have far exceeded, in this modern age, the old bounds, that they have been swollen up to giant proportions, while, all the time, the stature and intellect of man remain unchanged. It is therefore above all things important that the moral philosophy and spiritual conceptions of men and nations should hold their own amid these formidable scientific evolutions.

Still he saw hope: “the genus homo is a tough creature who has travelled here by a very long road. [Man’s] spirit has, from the earliest dawn of history, shown itself upon occasion capable of mounting to the sublime, far above material conditions or mortal terrors.”

“Churchill’s trial is also our trial”

Reviewing a book of Churchill calumnies, most of them false or distorted, Peter Baker powerfully argued that Churchill deserves his monuments: “None of our historical idols were as unvarnished as the memorials we build to them. The question is: What are they being honored for?”

Churchill’s statues honor a leader who strove, as he said of Neville Chamberlain, “to save the world from awful, devastating struggle.” When the struggle came despite his efforts, he did not win it—that was not in his power. What he did in his finest hour, Charles Krauthammer wrote, was not lose it: “Without him, in 1940, the world now would be unrecognizable—dark, impoverished, tortured.”

Yet Churchill’s merit does not rest on 1940 alone. As Larry P. Arnn wrote in Churchill’s Trial, his entire life is an object lesson in the art of statesmanship: “Prudence, involving ‘calculating and ordering many things that shift and change,’ has from ancient times been held to be the defining virtue and art of the statesman.” His challenges were those of human nature and governance, relevant to his world and ours, Dr. Arnn wrote: “Churchill’s trial is also our trial.”

“A little nearer to our own times”

Of the subject of those statues Sir Martin Gilbert wrote:

Churchill was indeed a noble spirit, sustained in his long life by a faith in the capacity of man to live in peace, to seek prosperity, and to ward off threats and dangers by his own exertions. His love of country, his sense of fair play, his hopes for the human race, were matched by formidable powers of work and thought, vision and foresight. His path had often been dogged by controversy, disappointment and abuse, but these had never deflected him from his sense of duty and his faith in the British people.

“How strange it is that the past is so little understood and so quickly forgotten,” WSC wrote a friend in 1929. “I have tried to drag history up a little nearer to our own times in case it should be helpful as a guide in present difficulties.”

How do we do that? To paraphrase the words of a famous American admirer: Ask not what Churchill would do now. Ask what we should do, bearing Churchill firmly in mind.