Paul Addison, 1943-2020: What Matters is the Truth

29 October 1994

A Corpus of Excellence

Paul read for an undergraduate degree at Pembroke College, Oxford before moving to Nuffield College, Oxford for postgraduate study. In 1967 he became a Lecturer at Edinburgh University and subsequently a Reader for twenty-three years. He became an Endowment Fellow in 1990, and Directed the Centre for Second World War Studies from 1996 to 2005.

Paul wrote for the Times Literary Supplement, the New Statesman and the London Review of Books. Primarily, his wife Rosy remembers, he aimed “to make making history accessible, understandable and comprehensible to his fellow human beings.”

We met in mid-1994, when Barbara and I hosted our seventh Churchill Tour. Our second in Scotland, it was a notable adventure, taking us all the way to Scapa Flow in the Orkneys. There we saw, on full-color sonar, the shape of HMS Royal Oak on the bottom—torpedoed by U-47 in 1939. It was an eerie image, like that of USS Arizona at Pearl Harbor. Our tour began with a vast exhibit of Churchill in political cartoons, organized for us at Edinburgh University by Paul, and David Stafford, his longtime colleague. From then on, I paid attention, and read every book of theirs I could lay my hands on.

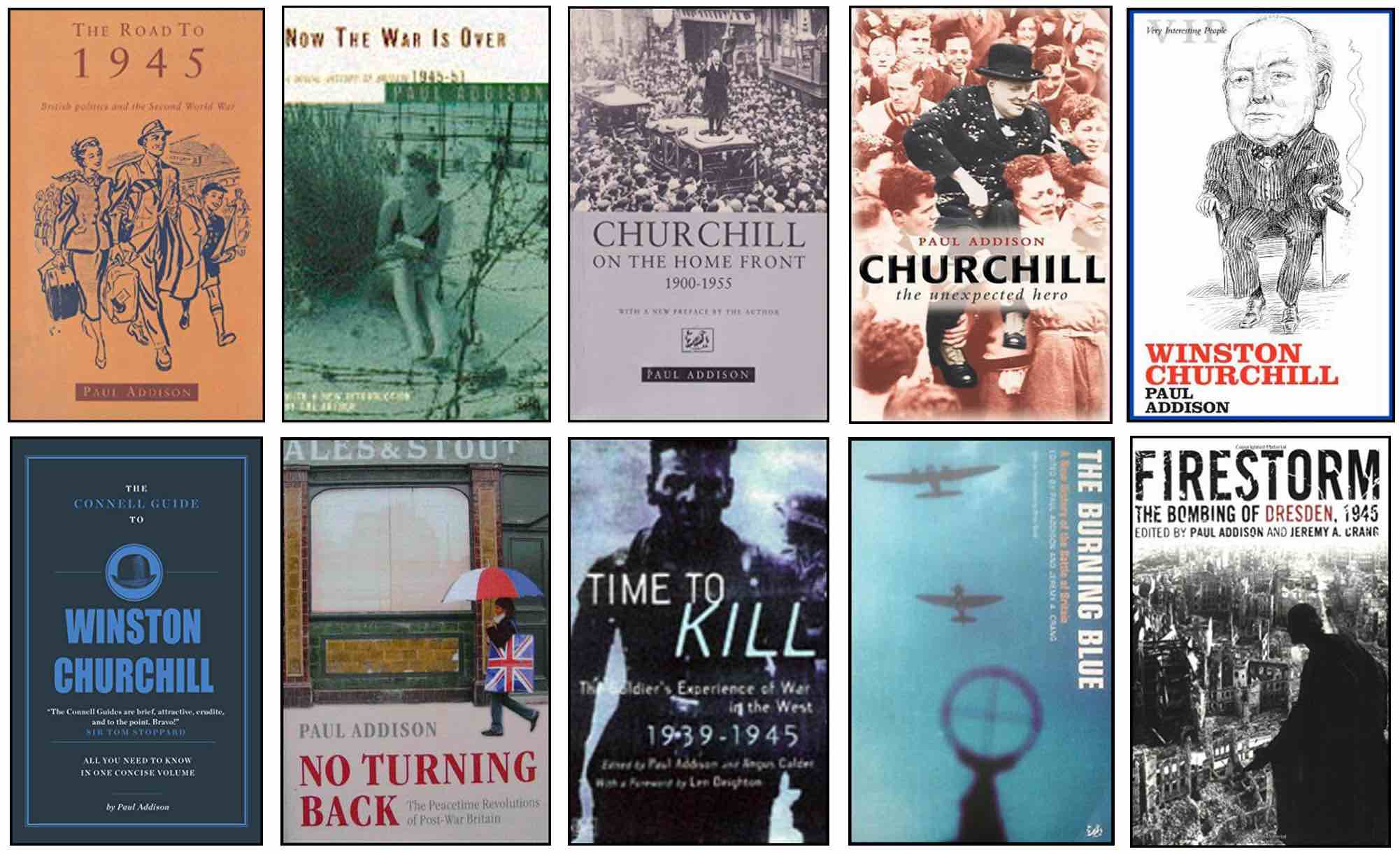

Paul Addison wrote and edited ten Churchill works, listed below. His classic, still a “standard work,” was Churchill on the Home Front (1992). Atypically for most Churchill writers then, Paul took the approach of studying the domestic side of WSC’s politics. Until this book, the prevailing impression was that Churchill was bored with domestic issues. Methodically Paul showed how completely wrong that was, weighing the evidence with grace and understanding.

“High sense of the British moment”

Paul understood the statesman’s greatness, warts and all. “Which warts,” William Buckley said, “do not deface Churchill because of the nobility of his cause, and his high sense of the British moment.” Nothing will ever surpass 1940—but Churchill accomplished much else. Paul limned the peaks, and the valleys. Churchill’s faults like his virtues were on a grand scale, he would say. But there’s no doubt that the latter heavily outweighed the former.

Here is an example: Churchill’s youthful fling with Eugenics, and the idea of sterilizing the mentally incompetent. There was quite an uproar about this when it was “discovered.” (Read: someone finally found it in the public records.)

Churchill’s Eugenics was a fling because he abandoned it quickly, along with most intelligent people. But some readers were outraged. “I can never think good things of him again,” one said. “No truly educated intelligent person could adopt such views.” (Well…a lot of educated intelligent persons happily adopted Nazism and Bolshevism.)

Dr. Addison showed us the balanced way to look at this issue. Churchill’s intentions were benign, he wrote. “but he was blundering into sensitive areas of civil liberty.” Then he drew a deeper lesson no one else had contemplated:

Yet it is rare to discover reflections of a politician on the nature of man. Churchill’s belief in the innate virtue of the great majority of human beings was part and parcel of an optimism he often expressed before the First World War.

This was perceptive, broadminded and fair. And Paul also explained why Churchill was unique. Few politicians reflect on “the nature of man.” Fewer still believe “in the innate virtue of human beings.” Such understanding is a rare thing among writers of history.

His Work Abides

Books by Paul Addison

The Road to 1945: British Politics and the Second World War 1 (1977, rev. 1994). A rigorously researched study of the crucial moment when political parties put aside their differences to unite under Churchill and focus on the task of war. But the war years witnessed a radical shift in political power, dramatically expressed in Labour’s decisive victory in 1945.

Now the War Is Over: A Social History of Britain, 1945–1951 (1985, rev. 1994). Vast changes in British society followed the most destructive war ever known. Britain reshaped itself with high ideals and a collective desire to enjoy the fruits and opportunities of peacetime.

Churchill on the Home Front 1900-1955 (1992). “A tour de force on Churchill as a domestic figure rather than as the bulldog wartime leader, and a subtle portrait of him as a politician. Addison revises the view of Churchill as uninterested and out of his depth in domestic affairs, painting a nuanced picture of a canny parliamentarian.” —Kirkus

Churchill: The Unexpected Hero, Lives and Legacies Series (2005). In the Second World War, Churchill won twice: over Nazi Germany, and over a legion of sceptics who derided his judgement and denied his claims to greatness. One of the best “brief lives” ever published on Winston Churchill.

* * *

Winston Churchill, Oxford VIP Series (2007). Text from Dr. Addison’s Churchill entry for the new Dictionary of National Biography. Hailed as a miniature masterpiece, an even briefer life than Unexpected Hero. It is dramatic and penetrating despite fewer than 150 pages. The ideal book to read if you read nothing else about Churchill.

No Turning Back: The Peacetime Revolutions of Post-War Britain (2010). Studies the vastly changing character of British society since the end of the Second World War. A series of peaceful revolutions transformed the country. The peace and prosperity of the second half of the 20th century appear as more powerful solvents of settled ways of life than the Battle of the Somme or the Blitz.

The Connell Guide to Winston Churchill (2016). A short, incisive guide based on the author’s Dictionary of National Biography entry. Text is arranged in Q&A format and designed to answer young people’s questions about Churchill. It analyzes his extraordinary career and looks at the radically different ways in which historians have seen him.

Editor – Contributor

Time to Kill: A Soldier’s Experience of War in the West (1997). Foreword by Len Deighton. Papers by numerous scholars. Based on a University of Edinburgh symposium on the Second World War seen through soldiers’ eyes, from Africans under European to command, to Soviet women fighting alongside the men, to ordinary “squaddies” on the front lines in all theaters of war.

The Burning Blue: A New History of the Battle of Britain (2000): Paul and Jeremy Craig compile the work of seventeen accomplished historians on every aspect of a history-changing battle. No survey could be more wide-ranging or fascinating. First published in 2000 to mark the 60th anniversary of the Battle, since reissued.

Firestorm: The Bombing of Dresden, 1945 (2006). Paul, Jeremy Craig and a panel of experts reassess the evidence and the issues, including whether the Dresden bombing constitutes a war crime. The book considers why Dresden has come to raise military and ethical questions on the waging of total war.

Further tributes

Ian S. Wood’s eloquent memorial in The Scotsman: “Paul had no time for some of the simplistic vilification of Churchill that crept into this debate. He saw Churchill as someone of volcanic energy and true courage, though unable to shake off the prejudices of the era which had formed him…. In the end, Paul wrote, ‘the recognition of [Churchill’s] frailties and flaws has worked in his favour. It has brought him up to date by making him into the kind of hero our disenchanted culture can accept and admire: a hero with feet of clay.'”

The Hillsdale College Churchill Project shortly publishes my separate tribute from a scholarly aspect, together with a compilation of all his Churchill writing from his university thesis to articles, contributions and chapters in other books by Professor Antoine Capet.

One thought on “Paul Addison, 1943-2020: What Matters is the Truth”

A lovely obituary for a lovely man. The phrase “a scholar and a gentleman” was surely coined with Paul in mind. He was an encouraging and inspiring teacher and a kind colleague.

Comments are closed.