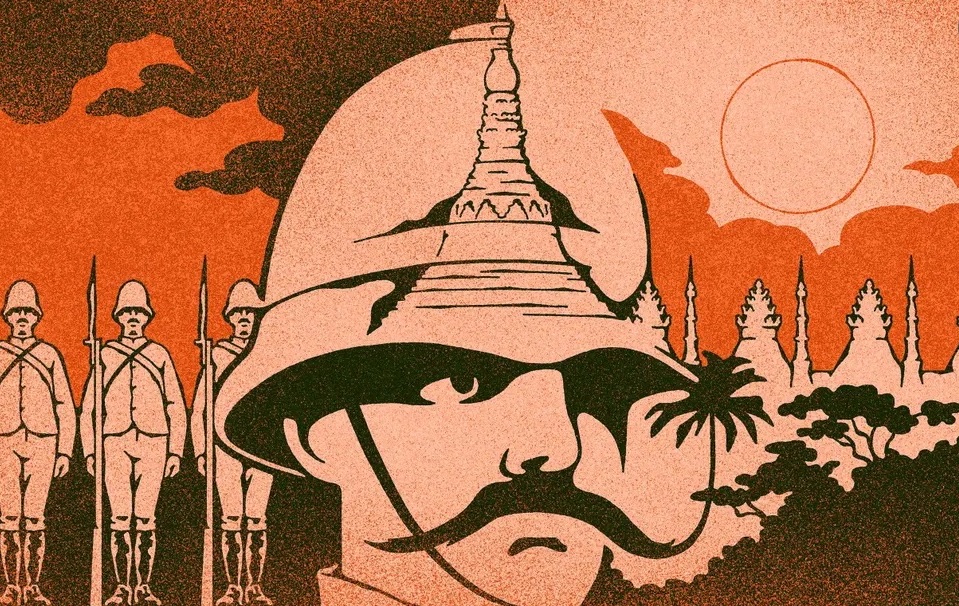

Boris, Racism, Imperialism, and “The Road to Mandalay”

Prime Ministers are always popular targets, and Boris Johnson wore the bullseye as well as the rest. One shaft was directed at his “insensitivity” in reciting “The Road to Mandalay” on a visit to Myanmar (formerly known as Burma). In the immortal words of John Kennedy, let us say this about that.

* * * * *

Mandalay as dog whistle

Mandalay as progressive poetry?

A friend who never read the poem before sent me his impression: “It seems to recall the allure and beauty of a country where a soldier was asked to do a dangerous job, and a people he later longed to be with again.”

Let’s go even further. If we want to be fair, isn’t Mandalay a remarkably progressive 1890 endorsement of interracial harmony? Interpreting it as mere lust after “an exotic object and someone to be ‘civilized'” only displays ignorance. Clearly the writer didn’t read it well. It contains no expressions of lust, only loneliness. That is what Kipling’s soldier is saying. He wants to go back to a land and a girl he loves, and both are Asian.

Mandalay even indulges modern readers with a gesture of Political Correctness. The soldier says, “We useter watch the steamers an’ the hathis pilin’ teak.” Then he hastens to explain: “Elephints a-pilin’ teak.” (The Hindi word for “elephant” is “haathee.”) That is no less a bow to P.C. than our modern haste to call Burma by its new name Myanmar—proclaimed in 1989 by the ruling military junta.*

Boris’ undiplomatic foray

In 2017, on a visit to Myanmar’s magnificent Shwedagon Pagoda, Boris Johnson was overcome by nostalgia. Suddenly he began reciting, “At the old Moulmein pagoda….” Psst., whispered the British Ambassador, “that’s probably not a good idea.” (Did he think Myanmar’s leaders study Kipling?)

Covering this at the time was The Guardian‘s thoughtful Ian Jack. The Guardian is no right-wing mouthpiece, and Mr. Jack excoriated Boris for being undiplomatic. Fair enough, though Johnson was probably just giving in to schoolboy romanticism. But what Mr. Jack writes about Kipling is worthy of consideration:

Postcolonial studies can have few richer specimens to tease apart in the space of 51 lines: race, class, power, gender, the erotic, the exotic and what anthropologists and historians call “colonial desire”…. Kipling wrote poetry and prose that certainly deserves the epithet, notably The White Man’s Burden. He was a child of empire, and became the empire’s laureate. But Mandalay isn’t so much an argument for colonialism as an evocation of its personal effects….

There is always, eventually, an awkwardness with Kipling: the race and empire issue. [Historian Geoff] Hutchinson got round it by having his Kipling say something to the effect that he knew his views grew out of different time—though even in that different time, Kipling was unusually committed to mystical ideas of national character and destiny. [Emphasis mine.]**

“A different time” is how unread people try to excuse what others call the racist imperialism of Churchill. But like Kipling, Churchill had more admirable and deeper motivations. Ideas about liberty and human rights. Among them were “the mystical ideas of national character and destiny.”

Appreciating The Road to Mandalay

You could hear a tame, ironized echo of these ideas in Boris Johnson’s speech to the Tory conference: “We are not the lion. We do not claim to be the lion…. But it is up to us now—in the traditional non-threatening and genial, self-deprecating way of the British—to let that lion roar.”

Endnotes

I do not consider that names that have been familiar for generations in England should be altered to study the whims of foreigners living in those parts. Where the name has no particular significance the local custom should be followed. However, Constantinople should never be abandoned, though for stupid people Istanbul may be written in brackets after it. As for Angora, long familiar with us through the Angora cats, I will resist to the utmost of my power its degradation to Ankara.…

Bad luck…always pursues people who change the names of their cities. Fortune is rightly malignant to those who break with the traditions and customs of the past. As long as I have a word to say in the matter Ankara is banned, unless in brackets afterwards. If we do not make a stand we shall in a few weeks be asked to call Leghorn Livorno, and the BBC will be pronouncing Paris “Paree.” Foreign names were made for Englishmen, not Englishmen for foreign names. I date this minute from St. George’s Day.

Further reading

Ian Jack in The Guardian: “Boris Johnson was unwise to quote Kipling, but he wasn’t praising empire.”

Grad-Saver: The Poems of Kipling: An Analysis of Mandalay.

Wikipedia carries a balanced set of pro and con arguments on this subject.

One thought on “Boris, Racism, Imperialism, and “The Road to Mandalay””

I am a Myanmar Buddhist and wish to make two points. (1) Kipling’s poem “Mandalay” does not upset me unduly; it was in colonial times (during which my parents grew up). But Myanmar people fluent in English like me (the poem has not been translated yet) find the characterization about Lord Buddha’s image and Buddhism as practiced in my country offensive. And not withstanding your remark, “Did he think Myanmar’s leaders study Kipling?” enough still read English poetry. (2) You comment about “our modern haste to call Burma by its new name Myanmar—proclaimed in 1989 by the ruling military junta.* This is patently false. It had always been Myanmar in our temple inscriptions of the 12th century. Myanmar is named after the main ethnic group, just as Thailand takes its name from the Thai. Ignorant foreigners do not realize this and try to politicize the name because Aung San Suu Kyi had refused to use it. It is neither new nor invented by any military government. “Burma” is simply the British colonialist mispronunciation of the word “Bamar” (actually pronounced B’mah), which in itself is the vernacular form of our national language, while the official form is called “Myanmar” (pronounced Mia-Mah) and has been thus so since the Bagan era, as documented in our stone inscriptions.

–

Thank you for your observations. (1) I think you are quite right to consider Kipling’s 1890 poem in the context of its time. Likewise its ignorant wisecrack by a British soldier: as I said, the only offensive line in the poem. As a whole the poem expresses admiration for the country and its people, comparing them favorably to the British, which must have been off-putting to certain Victorians. Perhaps we all should step back from taking “offense” at trivia. (2) I did not say “Myanmar” was “new” or “invented” by the ruling junta, but they certainly did proclaim it, in 1989, although a third of the country is not Bamar. As you point out, “Burma” and “Myanmar” amount to the same thing, but perhaps the 1989 change was proclaimed for political rather than etymologic purposes. -RML

Comments are closed.