How “Goeben” Changed History, by Dal Newfield

It is 40 years since this Goeben story, and the passing of its author. Without Dalton Newfield there never would have been an International Churchill Society—at least not the one many of us knew, worked for and cherished for long years.

The organization arose from an unlikely pastime—philately. It attracted Dal’s interest because, while a devoted all-purpose “Churchillian,” he was also a stamp collector. His enthusiasm was infectious, combining an encyclopedic knowledge of Churchill with our own passing interest in Churchill commemorative postage stamps.

Newfield created an informative adjunct to Churchill philately with what he called “CRs”—Churchill-related stamps not depicting him but closely involving him. They were a mainstay of the original Churchill Study Unit until it morphed into the larger Churchill Society. That too, was the work of Dal Newfield, who realized that stamps were but a blip in the Churchill story—that a broader approach was indicated.

Dal’s imagination produced many “CR” stories, among which this was most intriguing. It features the German battlecruiser Goeben, later the Turkish flagship Yavuz. It involves fateful decisions by the British Admiralty, and their effect on career of Churchill—which the activities of Goeben almost stopped in its tracks.

“For Want of a Nail”: The Goeben Story

by Dalton Newfield

In the early years of the 20th Century, Turkey was known as “The Sick Man of Europe,” torn between rival factions, between old and new worlds. On one side was Sultan Mehmed V and the conservatives. On the other was Enver Pasha‘s group, the Young Turks. They agreed about one thing: Russia must be ousted from the Caucasus.

Raising money by popular subscription, Turkey ordered two Dreadnought-class battlecruisers from Britain. They also asked the British to modernize their fleet, and the Germans to modernize their army.

By 1914 Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, was bringing England’s navy up to fighting trim. War was imminent, and the Turkish ships were almost complete. In fact, the crew of one was already standing by to take over. Churchill, unsure of Turkey, decided to commandeer the ships for the Royal Navy.

War between France and Germany was declared on August 3rd. The Turks, divided, were in a quandary. Enver Pasha, on his own, signed an alliance with Germany. The next day, panic stricken, he tried to make an alliance with Russia! Sultan Mehmed V stood fast for neutrality.

Drama in the Med

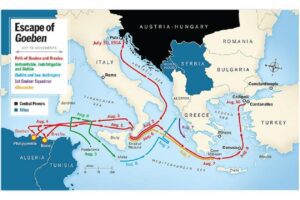

One of France’s best army corps was in North Africa, and with war threatening was needed back in France. To protect the crossing, France had a powerful navy. But the swiftest capital ship in the Mediterranean was SMS (Seiner Majestät Schiff) Goeben, a two-year-old German battlecruiser. She had just finished refitting in Pola, the Austro-Hungarian navy base on the Adriatic. Goeben was capable of making mincemeat of the French convoys.

On 30 March 1914, Admiral Lord Berkeley Milne, Commander-in-Chief of the British Mediterranean fleet, received new orders. Even then, war scares were prevalent. Milne’s primary mission was to protect French convoys from Goeben, and not to let Goeben escape into the Atlantic. This was tall order, since war had not yet been declared by any country.

Milne sent a force of light warships under Admiral Charles Troubridge toward the mouth of the Adriatic. He concentrated the rest of his forces including HMS Indomitable and Indefatigable, at Malta. Together the two forces were capable of destroying Goeben.

Then the French had second thoughts about crossing the Mediterranean at this time. Inexplicably, they did not tell the British of this decision. Next, Italy declared herself neutral and Britain informed Italy that she would respect her neutrality within six miles from Italian shores.

Easy prey

On August 2nd Goeben coaled at Messina, then, with her accompanying cruiser SMS Breslau, bombarded the French North African ports of Bone and Philippeville. On that day Britain sent an ultimatum to Germany: Get out of Belgium by midnight. At about 3pm, west of Sicily, Goeben passed within 10,000 yards of Indomitable and Indefatigable—easy prey for the British, who could fire three times more metal at Goeben than she could return. Troubridge regretted that the German admiral’s flag was not flying. Otherwise he would have fired a salute which, in view of the tense situation, might have precipitated war on the spot.

In London, Churchill and the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, begged the Prime Minister, H.H. Asquith, to allow the British warships to strike. Asquith agreed, but the Cabinet declared it would not be “cricket” to fire before the British ultimatum expired on August 4th. The German ships steamed away unmolested.

Goeben returned to Messina where she topped off her bunkers. Again, the British could have sunk her with little trouble. Again, it was decided that to attack her inside Italy’s six-mile limit was unsporting.

German Konteradmiral Wilhelm Souchon made out his will and sailed south out of Messina, to what he was sure would now be the long-awaited British attack and his almost certain death. To his surprise, only light cruisers awaited him. Milne’s force was still to the west, screening nonexistent French convoys!

Escape of Goeben

Then the second inexplicable incident occurred: Indomitable needed coal, but Milne, instead of sending her to Malta—where the operation would take less time and from where she could cover Messina and the Adriatic—sent her to Bizerte, North Africa. There she was well out of the action. Goeben and Breslau sailed for Pola at the head of the Adriatic, with only Troubridge’s light warships in their way.

Suddenly the German ships altered course to the east-southeast. Admiral Souchon had been advised of the chances of a German alliance with Turkey. The British, still ignorant of the situation, were puzzled. Milne gave Troubridge no orders, so finally he decided to give chase, hoping to get in at least a crippling blow before daylight.

Then the third inexplicable event occurred. Troubridge had 16 vessels, far more than Goeben could sink with the ammunition in her hold. Despite this advantage, Troubridge decided the odds were against him, and turned back to the Adriatic! Milne, by then, was coming up at flank speed.

Then the fourth inexplicable event occurred: A clerk in the Admiralty office, without any authority at all, radioed that war had been declared against Austria-Hungary. Milne’s orders were clear. He reversed his course and headed for Malta. It was 24 hours before Milne’s course was noted and reversed. Except that the British still could not imagine where Goeben was headed, the chase now looked hopeless. But was it?

Another opportunity lost

In Constantinople Enver Pasha and Sultan Mehmed were still at odds. For almost two days Goeben and Breslau wandered about the Greek islands, awaiting permission to pass into the Dardanelles. Finally they were allowed through. With her arrival, Turkey’s alliance with Germany was sealed.

Still the British did not know of the alliance. Winston Churchill protested the presence of Goeben in a “neutral” port, demanding she be interned. Germany responded by announcing that Goeben and Breslau had been “sold” to Turkey. It was a blatant ruse that Churchill recognized. He ordered her sunk if she came out, “regardless of what flag she flew.”

On October 27th Goeben, in company with the Turkish Navy, steamed into the Black Sea, bombarded the Russian fortress of Sevastopol, sank a transport, raided Odessa, torpedoed a gunboat and practically destroyed Novorossiysk, its oil tanks and all the shipping in port. At last the British declared war on Turkey.

“For want of a nail…”

But why is a Turkish commemorative showing the battlecruiser Yavuz a Churchill-related postage stamp?

Had Goeben not passed the Dardanelles, it was very possible Turkey would have remained neutral in the First World War. Absent Turkey, the Allies lost their only supply route to Russia. This loss was so serious that in 1915 Churchill felt it imperative to assault the Dardanelles. The resulting debacle was the principal reason Churchill was ousted from the Admiralty. Because of Goeben, the Russian armies starved for food and materiel. The Czar fell and the Bolsheviks took over. And the rest is history….

Yavuz and her fate

After being mined several times, beached and bombed by Handley Page bombers, Goeben was given to the Turks in the Treaty of Lausanne. She was ultimately refitted and renamed Yavuz Sultan Selim. She served as flagship of the Turkish Navy until 1954.

Yavuz was offered to West Germany as a museum ship in 1963, but the artifacts of the Kaiser’s war were not popular, and the offer was turned down. She was sold for scrap in 1971. Yavuz was the last Dreadnought in existence outside the United States and the longest-serving of all Dreadnought-class warships. She was also the last survivor of the Imperial German Navy.

One thought on “How “Goeben” Changed History, by Dal Newfield”

Very well done story. Interesting to learn she was the last survivor of the old Imperial German Navy.

Comments are closed.